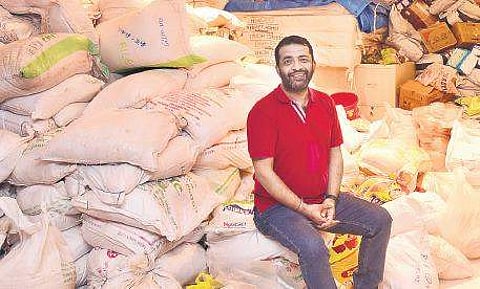

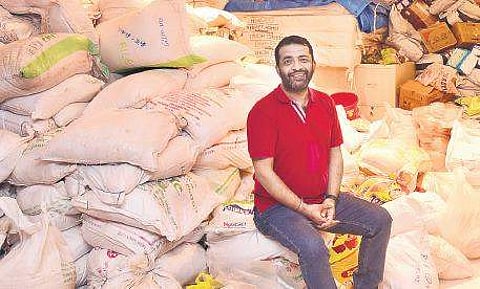

KOCHI: During his travels in Ernakulam district following the massive flooding in Kerala, Magsaysay Award winner Anshu Gupta came across a man feeding a banana to his cow. It was the first time in Kerala that he had seen this scene. “Nobody was bothered about the animals,” says Anshu, at the relief collection hub in the basement of the Gold Souk Mall, Kochi. “Many had died. Because of water everywhere, there was no fodder for the animals.”

In front of the man’s house, his paddy field was under water. The man told Anshu, “I know people like you will give us rice and other materials. But the fact is that, after you go, nobody will be there for me. I have lost everything.”And so have lakhs of people in Kerala. “People have lost financially, emotionally and physically,” he says. “Malayalis are not like the people of Uttar Pradesh, Assam and Bihar, who have, over time, become resilient because floods happen so often in their areas. This is a new experience for the people of Kerala.”

And Anshu questions the assurances that have been given by some senior people in the administration that the flood-affected have received a lot of relief. “If we think that by giving 5 kgs of pulses and 10 kgs of rice, everything is normal, that is not true,” he says. “The people need food for several months before they are able to start earning themselves.”

Anshu runs Goonj (a Hindi word which means the echo of a sound] and, for the past twenty years, they have been working in 22 states including disaster-prone areas like Assam, Bihar, Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand.In fact, he found a few similarities between Kerala and the Uttarakhand disaster of 2013. “The force of the water in Kerala was similar to the floods at Uttarakhand,” he says. “But since the government machinery in Kerala operated in a far more efficient manner, along with the Army, Navy, the local people as well as the fishermen, there were far fewer deaths. This is highly commendable.”

Asked about the future, Anshu says, “Kerala will recover. Every state ultimately recovers. That is the resilience of the people. Roads and bridges will come back. However, recovery, to me, is whether the people will have the same lifestyle they had before the disaster. I fear the quality of life may go down for some time.”

But he wonders whether Keralites will learn a lesson from this. “Will the people carry on building concrete structures all over the place or will they become environmentally conscious now?” he says. “Instead of agencies and organisations interfering, we should leave it to the people to rebuild the structures in the way they think is suitable, under certain guidelines. Many multi-storied buildings collapsed because they were made on the slopes of hills and it was not on a secure footing. It will be sad if it is rebuilt in the same way.”

Anshu has reasons to be pessimistic. “In Jammu and Kashmir and Uttarakhand, the people rebuild the buildings in the same way it was before the floods,” he says. “The calculation was that these floods will happen once in 50 or 100 years.”Anshu pauses and says, “But nothing is predictable these days, thanks to climate change and other factors.”

Life and career

Anshu’s turning point happened when at the age of 16, he was travelling pillion on a motorbike, which hit a tractor at Dehra Dun. “Like a Bollywood movie, I sailed over the tractor and landed in a ditch,” he says. “I was unharmed except for my foot.”

However, at the government hospital, the doctor asked for Rs 400 to do the surgery. Anshu’s father, an honest government official, refused. As a result, the surgery was not done properly. “To this day, I am in continuous pain,” says Anshu. “But I have respect for what my father did. I tell people that if my father had paid Rs 400 I would have been standing on a bribed foot, but today I stand on my own foot.”

Another turning point came when as a college student he went to Uttarkashi in 1991 to help with relief efforts following a massive earthquake. “It was my first exposure to the problems faced by the rural people,” he says.

Seven years later, while working as a corporate manager, in a private firm, Anshu felt the urge to start a social service organisation. And that was how Goonj was born. “I feel my career as a social entrepreneur is a calling from God,” he says. Today, Goonj has numerous schemes to help the poor and downtrodden. In fact, in their impressive book, ‘100 Stories of Change’ it tells about how Goonj helped communities change their lives by making them build walls, dig wells, clean ponds, make bridges, roofs, sanitary pads, and do disaster relief.

They are paid not by cash but through Goonj’s ‘Cloth for Work’ initiative.

Not surprisingly, Anshu’s work, done with the help of his wife Meenakshi, whom he calls his ‘backbone’ and his daughter, has received accolades. In 2015, Anshu was awarded the prestigious Ramon Magsaysay Award. “When I stood on stage, at Manila, I missed my parents, both of whom have passed away,” he says. “But the award was a reaffirmation of the work we are doing. I felt that we are on the right path.”

But the surprising aspect of the win was how the villagers in many communities across India, where Goonj has worked, celebrated it by distributing sweets. “It was so heart-warming,” he says, with a smile.