Under the scorching sun, fabrics lay stretched end-to-end on the barren grounds like rows and columns of an Excel sheet, a few kilometres away from the Bhuj-Bhachau highway at Ajrakhpur in Gujarat. Some white and some indigo coloured.

And a little ahead, Ismail Mohammad Khatri runs his Ajrakh Studio in a whitewashed flat-roofed one-storey house with an ornate wooden door. Inside the spotlessly clean emporium, manager Abdul Rahim plays a video about the Ajrakhpur block-printed fabrics.

On the banks of the Indus river, Ajrakh printing flourished in the bygone days of history. The word Ajrakh is coined from Arabic word ‘Azrak’, which means blue. Understandably, the excessive usage of indigo in Ajrakh prints must be the influence behind the name.

Dhamadka, a village 57 km away from Bhuj, used to be the habitat of Ajrakh style of block printing. But the 2001 earthquake crumbled the village into ruins and caused the water level to drop due to which the iron content increased in the water. “The ferrous nature of water was a deterrent in creation of the Ajrakh block prints. And the artists were forced to look for lands elsewhere. So, they searched for a suitable habitat and zeroed in on Ajrakhpur, aptly named after their craft,” says Rahim, who has been into the profession since 2012, and works as a manager at the emporium.

Over 500 artisans like him are now earning their livelihood through block printing, besides keeping the tradition of handicrafts alive. A worker earns `7,000-11,000 per month.

“Ajrakh is a time-consuming process. It is done on fabrics such as cotton, wool and silk. First, the textile is washed to remove starch. Then it is immersed in a mixture of camel dung, soda ash and castor oil. It is semi-dried and the process is repeated about 9-10 times,” says artisan Abdul Razzak, who works at Ismail’s workshop that is two-minute drive away from the emporium. “Cherryplum, which acts as a mordant, is used to wash the clothes before drying them in the Sun.”

Wooden blocks with symmetrical patterns are then used to outline the design in white. The whiteness accrues from the use of lime, a substance that ensures smudge-free contour. Scrap iron, jaggery and tamarind seeds are processed manually and transformed into a black paste that serves as black colour.

“Another round of resist printing follows, the material used is derived from an amalgamation of gum Arabic, clay and alum. Saw dust is sprinkled generously over the printed part to prevent smearing of clay. And it is left to dry for some days,” says Razzak.

Then, the fabric is dyed in indigo thrice and washed thoroughly before attaching the final colours to it. Henna gives a light-green tinge, madder root is used for dying orange and rhubarb root gives a brownish tint. The alum residue enhances into bright red when the cloth is boiled with Alizarine.

“We procure the madder roots from the Himalayan terrains in India and from Iran. Since we use only naturally occurring elements, our workers are never exposed to chemicals and their health does not get affected,” says master craftsman Khatri.

The motifs used for block printing are inspired by nature, Islam and the typical lifestyle that prevails in Kutch. It takes as long as a fortnight to finish one piece of cloth.

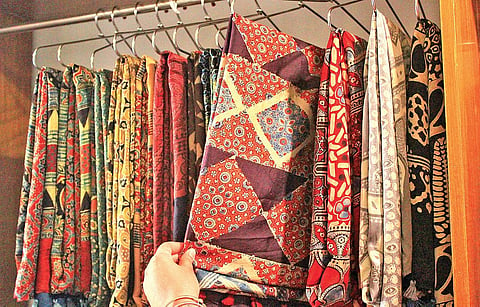

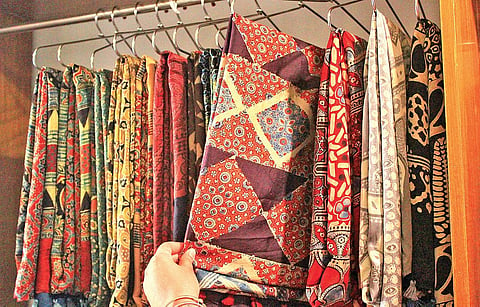

The clientele of the Ajrakh printed products—sarees, dupattas, stoles, bedsheets, and ethnic jackets—are now spread across India in cities such as Kolkata, Hyderabad, Mumbai, Durgapur and has reached international markets.

In the modern era when Earth is oversaturated with chemicals, struggling with unemployment, Ajrakh industry comprising 51 workshops in Ajrakhpur serves as an excellent example of the sustainable business model.