Punishing water crisis, endless traffic jams, toxic vehicular pollution, mounds of litter, unchecked development and ad hoc construction are turning India’s summer retreats into unwelcome and unsustainable hot spots

Chilling out in a popular Indian hill station is no more a hot proposition this summer. Shimla, the legendary summer capital of the Raj, once famous for its meandering boulevards, English fruit orchards and walks lined with trees and flowers is a slum. Except for the random Gothic villa, its great verandah-fronted bungalows, Tudor cottages and picturesque chalets have been razed by indiscriminate building spree in the 1990s. An imperial city, which thrived on high society invitations, teas, strolls, picnics, dinners, balls, fetes, races and amateur theatricals, is in the grip of a tourist invasion from the plains, escaping the scorching summer heat. The story is the same in Kasauli, Mussoorie, Ranikhet and other summer retreats. A reverse metamorphosis of sorts is happening to the hill stations: the beautiful butterfly has turned into an ugly caterpillar. Says author Ruskin Bond who has spent most of his adult life in Mussoorie, “These places survive on tourism. So tourists cannot be discouraged. I wish a little more attention is given to caring for the surroundings and encouraging sustainable tourism.

We need tourism, but we also need to preserve the beauty and sanctity of the mountains.”

Bond may be right but Indian hill stations are collapsing due to reasons well within our control.

• A water crisis of Himalayan proportions that could have been avoided.

• Burgeoning tourist traffic causing automobile pollution, interminable traffic jams clogging roads not built to accommodate such vehicle inflow, rampant littering of non-degradable material, waste generated by roadside restaurants and eateries.

• Rampant misuse of precious natural resources.

• Uncontrolled development as builders of large resorts and small hotels on hillsides flout building norms.

The Raj, which invented the hill station as a pleasant seat of governance, and the Kiplingesque social centerpiece had an official hierarchy for its summer retreats. In the first category came Shimla, Darjeeling, Nainital and Ooty, names that have been taken from the pages of history and planted in vulgar tourist brochures. From imperial stations, these towns and their lesser cousins are plagued by the maladies of cities in the plains.

DROPPING DROPS

Shimla is a victim of progress. Every season, around one lakh tourists are added to its resident population of 1.72 lakh, wrecking civic infrastructure. The largest catastrophe to strike Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand is the mammoth water crisis in its hill towns. Shimla’s water supply comes from the five major sources—Gumma, Giri, Ashiwini Khad, Churat and Seog. Its water storage capacity is 65 million litres daily (MLD); while it gets only around 35 MLD, the demand is around 45 MLD. Its ecosystem is under severe stress, with low rainfall in winter and inadequate rain in summer bringing down natural reserves by half. Even when it rains in Nainital, Mussoorie and Ranikhet, no water conservation measures exist to check the run-offs. Last year, the Shimla residents took out a protest march to the chief minister’s house.

Social media was rife with “Stop visiting Shimla” posts. The annual International Shimla Summer Festival was postponed. Shimla resident Sanjay Thakur, who owns two hotels Marina and Comdere, is not convinced there is a water crisis in his town. He says, “I was born and brought up in Shimla, and in the 54 years that I have spent here, I would say that Shimla has changed for the better.” Where there is bureaucracy there is a crisis. Periodic confrontations between the state Irrigation Department and the Public Health Department in Shimla over the maintenance and supply of potable water have led to stagnation and contamination. The city’s water network was designed in the 1870s and has not been upgraded till today. Water tankers have become the norm in the city where Englishmen once fished in sparkling streams, as residents line up with buckets in summer.

Water tankers charge Rs 4,000 each, and people are lucky if they get public water supply once in three or four days. Most of the rainwater does not filter down through natural aquifers underground, preventing groundwater from being recharged. Government of India norms cap the daily potable water supply to urban areas in the hills to 135 litres per person. In Shimla, the price of a Rs 20 bottle of water went up to Rs 100 last summer. Says Thakur, “All big hoteliers have their own tankers.” In November 2018, the Supreme Court-appointed committee to monitor Mussoorie’s tourist flow discovered that the town received only 7.60 MLD against its peak summer demand of 14.5 MLD. Ooty in summer gets 50 to 60 per cent below its water requirements during peak tourist season in May and June. Rohit Sethi, who runs the homestay brand ‘Seclude’, which has properties in Shimla, Palampur, Kasauli, Lansdowne among others, says: “The largest problem hoteliers face in the hills is water scarcity. Hence, constant altercations happen with tourists who check in.” In the South, the Nilgiris’ hill stations are running dry. N Sadiq Ali, who owns the Ooty Coffee House, says, “This town is in the grip of a water crisis. There are not enough tankers to supply water even to hotels.”

There is a troubling side to Tamil Nadu topping tourist footfalls thrice in a row. Kodaikanal in the Palani Hills had 5,000 residents two decades ago which exceeds 40,000 now. But over a million tourists visit each year. A citizen body called the Palani Hills Conservation Council is working to stop ecological degradation from the tourist backlash.

Climate change has caused bizarre variations in weather. In winter, snow falls in Umrikhaal, a few km below Lansdowne in Uttarakhand, while in summer temperatures go up to 29 degrees. A local homestay has installed air conditioners and a high-powered generator in case a fallen tree brings down power lines. The absence of water harvesting has serious consequences. Many places depend on water taken through pipes from village water bodies, which deplete them in summer.

STIFLING SNARLS

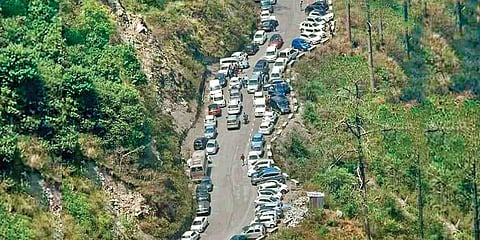

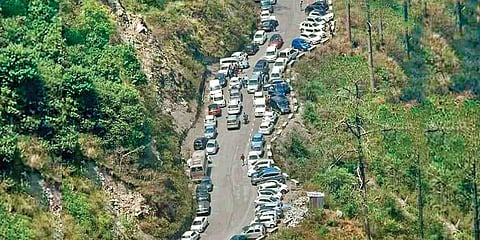

The nature of Indian hill stations has changed under the tourist onslaught. Darjeeling, which was famous for both tea and lush glory, is now a concrete jungle, stifled by tourist traffic. To make space for SUVs, picturesque walkways have been widened to make concrete roads in all hill stations. Vacation condos have come up, resulting in the cement trapping the ground water below. Sample this: An average of at least 4,500 and 5,000 tourist vehicles enter Manali and Shimla, respectively, every single day. Sethi says, “Hill stations today cannot take such large tourist inflows.” According to the traffic authorities, around 120 cops are deployed in Shimla to manage the chaotic traffic. Manali is worse.

Along with 120 constables, an equal number of homeguards are trying their best to bring order on roads. Nainital daily receives around 3,000 to 4,000 vehicles; their number rises to 6,000 on weekends. The city has only 2,000 parking slots. Ooty is no better. The burgeoning chocolate industry and connectivity

with Bengaluru and Coimbatore have become the bane of this lost imperial paradise. Hotels have put up notices asking tourists to go back.Coorg is being slowly devastated by plantation tourism: imagine, there are 3,500 home stays of which hardly 500 are on the government-approved list. The Karnataka Forest Department has restricted the number of trekkers on routes like Skandagiri and Kudremukh, which reeled under the trash epidemic.

Up north, Uttarakhand has woken up to the implications of the traffic crisis. The Nainital administration has decided to stop incoming vehicles once parking space is full. Last year, the police had put up ‘Nainital Houseful’ flexi-banners on approach roads. Convinced that these moves will undermine the hospitality business, the local hoteliers’ association launched a ‘blackout’ protest by switching off all lights between 6 pm and 9 pm for 24 hours last week. They have a solution: park tourist vehicles outside city limits and construct a shuttle service to ferry them into town. In April 2018, the Uttarakhand High Court had directed the state government to ensure that “those coming to Nainital with their own vehicles should first make advance arrangements for parking their vehicles”.

However, a traffic line snaking over almost five km on three approach roads choked all movement. The Mussoorie Municipal Board is planning to construct four additional parking facilities. The city is struggling to control its weekend tourist traffic even though around 100 additional traffic personnel have been deployed. Encroachment on roadsides and more buses for Yamunotri and Gangotri have added to the administration’s woes.

Says Mussoorie-born author-photographer Ganesh Saili, “A human tsunami has hit our hills this summer. Two years ago there was not a single shack along the 34-km ride up from Dehradun. Now there are 186 illegal shacks squeezing the heavy traffic into narrow arteries. Something has to give and it’s our turn this year.” In the Northeast where the British built hill stations like Shillong for strategic reasons, traffic snarls are an everyday affair. Says Faith Elvin, granddaughter of the legendary anthropologist Verrier Elwin, who was associated with Mahatma Gandhi and converted to Hinduism in 1935, “Shillong is still unspolit and green unlike many other hill stations, but traffic sometimes takes hours to clear in mornings and evenings.” Intrusive markets and a construction epidemic add to the crisis, sullying its pure mountain air with sulfur dioxide fumes.

HORROR HEIGHTS

If hill station roads are choked by traffic, the sidewalks are clogged by tourists. Twitter and Instagram were flooded last weekend with images of people sleeping in the open as hotels in Nainital and Mussoorie ran out of rooms. Almost 95 percent hotels in Shimla and 90 percent in Manali were full. Many tourists were forced to shelter at bus stands and when those ran out of space, slept on pavements. Even travellers with confirmed bookings did not have it easy. Kilometres-long traffic snarls lasting over five hours stopped many from reaching their destination—entire families slept in cars as they waited only to give up and drive back to city life, which suddenly seemed more inviting. Dozens of ATMs were out of cash in Manali, Kasol, Manikaran and Kullu in Himachal Pradesh last week. Sethi deplores the unregulated chaos, saying, “It’s like inviting people home for dinner and then there is no food. The situation in the hills is similar.”

However, the ‘must-visit’ nature of such places has encouraged many big private hotel chains to open shop. Forest land and plateaued hills have been cut down to construct massive resorts with tact official connivance. Says a Dehradun tour operator with deep sources in government, “Approval is easy given the price is right. There are enough loopholes in the law to be exploited.” Even less populated places such as Kanatal in Uttarakhand, Manikaran and Kasol are losing their charm. Tourists searching for ‘off-beat’ destinations end up overcrowding such places, which used to be virgin land not very long ago. Hill stations like Matheran in Maharashtra have woken up to bottlenecks and pollution. Jayesh Paranjape, founder-CEO of travel company The Western Routes, says, “In Matheran, vehicles are not allowed beyond a defined point. Only horses or toy trains can enter, or tourists can hike up to the town. Even if the place gets crowded, vehicular congestion is avoided.”

In the Nilgiris too, Ooty is chockablock with new hotels and markets, forcing hotel chains to seek space on the outskirts, thus eating into the green reserve of the mountains. Compared to last year, tourist flow has increased in the mountain ranges. Shoba Mohan, founder-partner of RARE India—a collection of boutique hotels, palace stays, wildlife lodges and homestays across the subcontinent—says, “We are seeing the aftermath of price-based promotion of destinations. Our tourism economy is based on numbers, and internet price wars boost traffic volumes the infrastructure cannot handle. There is no regulatory body controlling the number of hotel rooms per destination. Hence hotels have mushroomed all over the hills. And we are poor at self-regulation.”

STINKING MESS

With state governments doing little to roll back the damage, eco-volunters like Ankit Vasudevan work with many NGOs engaged in reviving tourist ravaged hill spots. In 2016, Ankit and some friends had visited Mahabaleshwar. “The sight I saw made it clear that we are killing the hills. Trash was everywhere—casually discarded empty plastic bottles and packets.” This eco-volunteer from Pune has been to Dehradun, Shimla and McLeodganj as part of many such initiatives. Sadiq Ali wants a committee involving local people to implement various ways to control traffic. Organisations such as Waste Warriors, Mountain Cleaners, Ecovita, Spiti Ecosphere are always looking for volunteers to clean up the hills. Difficult terrain and lack of garbage disposal means are challenges.

An official study in Tamil Nadu found that around 50 percent of hotels discharge their grey (non-toilet) waste teeming with bacteria and chemicals directly into the vegetation around or open pits, thus polluting both the ground and ground water. Since the infected ground water is later used for drinking, cooking and gardening, humans and animals are at risk of disease.

V Sivadass of Nilgiris Environment and Cultural Service Trust stresses, “The Nilgiris is not a tourist place. It is a biodiversity hot spot. We need to urgently preserve the town and the forests since the plains below get their water from the Western Ghats.” The Nilgiris was the first hill range in the country to implement the plastic ban. However, empty plastic bags, food wrappers and plastic bottles are choking the earth near water bodies and forests. Environmentalist Atul Deulgaonkar says, “Our wealth creation is totally based on destruction of nature and increasing pollution level, and loss of forest cover, but there are no policies in place.” Sethi agrees, “The Indian traveller is hardly ever conscious about his surroundings. They definitely need to learn and cultivate sustainable travelling.”

The River Beas, which gave Alexander the Great sleepless nights, is a plastic dump now. A recent report notes that Manali produces about 10 tonnes of garbage daily; the quantity shoots up to 50 tonnes during peak season. The Kullu Municipal Council, Bhuntar Nagar Panchayat and the Manali Municipal Council dump tourist-generated trash near the Beas. Despite directions from the Himachal Pradesh High Court and the National Green Tribunal, no alternative spot has been allotted to dump the waste. The Kullu civic body installed a biomedical waste incinerator which ironically had to be shut down because residents complained about the odour. The off-beat Nag Tibba and the Pir Panjal range are littered with empty beer bottles, cans, disposable plastic plates and cups, food wrappers, empty juice tetra-packs. Trekkers discard junk in the forests, endangering the fragile ecosystem.

SMALL AIN’T BEAUTIFUL

With infrastructure in the major hill stations crumbling, Lonely Planet motorists head for satellite hill stations like Dharamshala and McLeodganj. Temporary bridges have been constructed to reach the twin towns and makeshift roadside hotels are taking drive-ins. As a result, many dejected tourists to McLeodganj are forced by traffic jams akin to Delhi-NCR to turn tail and head for other destinations. The fact that after a court ruling, the administration cracked down on illegal construction and hiked the parking fee for the outstation bus stop resulted in the bus company shutting down operations. Says Saili about Mussoorie’s traffic jams, “All around me is the stink of cordite from burning clutches and over-heated brakes. It’s not just the rising temperatures, frayed tempers lead to fights on the slightest excuse. And flat-footers from the plains, unfamiliar with hill driving, end up in dreadful and oftener-than-not fatal accidents.”

Sattal, a quaint little hill station near Nainital, takes its name from the cluster of seven lakes in the vicinity. The youth there have started a Sattal Conservation Club to address the issues of garbage accumulation, depleting green cover and the declining eco-system. A member of the initiative says, “We need a proper waste management system in tourist areas. The government has to step in with proper guidelines and policies which should percolate to the last level.”

Perhaps the most shocking image this summer was the one that went viral on Twitter: a traffic jam on Mount Everest. The image and a corresponding video shows a snaking queue of mountaineers almost glued to each other while they make their way to the summit, one inch at a time. Sir Edmund Hillary and Sherpa Tenzing Norgay would have shaken their heads in disbelief and dismay—the Everest has become a tourist spot which rampant commercialisation has almost turned into a dump. The Nepalese authorities recently went in search of bodies buried on the Everest and came back with 11 tonne of garbage. So, if the world’s tallest mountain can become a traffic nightmare, what hope—if any—do we have for the places where the hills were alive with the sound of music and now replaced by the blaring of horns?

once upon a time

The hill station is a colonial British concept. Author of Early Penang Hill Station, geographer S Robert Aiken, writes that hill stations “offered isolated, exclusive milieus where sojourners could feel at home”. By the late 19th century, the viceroys and their councils spent twice the number of months they lived in Calcutta in Shimla every year. The governments of Bengal, Bombay, Madras, Assam, United Provinces, and Central Provinces made Darjeeling, Mahabaleshwar, Ootacamund, Shillong, Naini Tal and Pachmarhi their summer headquarters. The colonial army took to the climate like a Scotsman to the bog. Military cantonments came up in smaller hill stations. The largest number of hill stations was in the Himalayas. The well-defined criteria for a place to be a hill station were elevation and isolation respectively: high enough to escape the mosquitoes and summer heat and remote enough to be insulated from the natives. Around 25 of them were exclusive military hill stations. The majority population in others was well-defined—missionaries, planters, pensioners and railway workers. Dharamkot was home to Presbyterian missionaries. Coffee planters thrived in Yercaud. Lonavala was for employees of the Bombay railway system. Retired civil servants retreated to Madhupur. Solan still has the large brewery now renamed Mohan Meakins; Sabathu had a sanitarium for American Presbyterian missionaries and the Lawrence Military Asylum for children of British soldiers was in Sanawar. Then there were standalone multipurpose centres like Pachmarhi. Nora Mitchell, author of The Indian Hill-Station: Kodaikanal, lists 96 hill stations in India, around 20 of which were built after Independence.

With inputs from S Senthil Kumar