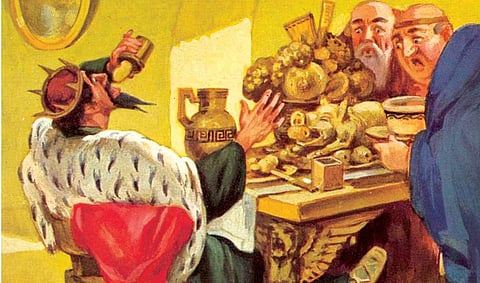

Midas, king of Phrygia, was granted a boon by Bacchus: Whatever the king touched, would turn to gold. Midas’s delight was short-lived. The food that he raised to his lips turned to yellow metal, as did the water he tried to drink. Desperate, Midas begged Bacchus to take back his baneful gift. The god took pity on the king and told him to bathe in a sacred river, which washed away the sin of specious enrichment.

We might not be so lucky. The fable of Midas has disturbing echoes today when genetic engineering promises to put within our grasp the cornucopia of endlessly replicated life. The biotechnology of cloning has already created its mitochondrial ewe in the form of Dolly the sheep.

The Noah’s Ark of the brave new world seems set to embark on a fantastic voyage at the end of which the animals will come out, not in twos but in their limitless multitudes. Technically—if not ethically—there would appear to be no reason why humans also cannot be produced on this genetic assembly line.

Despite widespread fears about what such an ‘industrialisation’ of humanity might lead to, the gathering momentum of genetic research could prove irreversible. One researcher has been quoted as saying, “It’s not a matter of should it (human cloning) be done, but when can it be done”.

According to reports, it already has been done, by accident. Belgian doctors who rubbed the surface of a frozen fertilised human ovum to facilitate implantation in the mother’s womb discovered, three weeks later, that the egg had divided to develop two embryos following the friction treatment. The result was identical twins today who are living in southern Belgium.

Cloning has become the new Frankenstein’s monster. The cloning of more productive livestock has been extolled as an economic miracle and denounced as a transgression of natural laws. The deliberate cloning of humans, though still in the realm of science fantasy, has provoked an outcry against a host of test-tube hobgoblins from mass-produced Nazis to captive organ farms, which could be harvested and cannibalised by affluent patients in need of transplants.

Such extreme and unlikely scenarios apart, it is clear that the issue raises a thicket of prickly social, legal and philosophical questions, which we are ill-equipped, both intellectually and emotionally, to answer. Like Midas, we have been given a seemingly divine gift, which could turn into a self-destructive curse.

The Midas touch and the biotechnician’s clone of thorns encompass a single quest: both represent the human yearning for everlasting life. Using the technique of engineered cell division, cloning seeks to usurp the sovereignty of creation—along with that of its inevitable concomitant of dissolution and death—and reward its adherents with an ersatz immortality.

The legend of Midas expresses the same desire, employing the metaphor of incorruptible gold as an allegory of deathless life. The Midas myth is a foreshadowing of the alchemists’ search for the so-called philosopher’s stone, the magical substance, which supposedly could transmute base metals into gold.

Sixteenth century alchemists used the sorcerer’s cloak of secrecy to mask a far greater enterprise than that of the molecular transformation of metal: what they sought was the transubstantiation of perishable flesh into an imperishable prototype.

C G Jung notes that the ostensible making of gold was a red herring, a diversionary symbol for the “transformation of the personality through the merging of the elements, the conscious and the (collective) unconscious”. Marlowe’s Faustus, who sold his soul to the devil in exchange for knowledge of the secret lore and who longed for the kiss of immortality from the lips of long-dead Helen, was an anachronistic ‘clone’ of the alchemists, and of Midas.

The fugitive desire for a surrogate perpetuity has adopted many guises in many cultures: from the birth of Minerva, goddess of learning, who sprang forth fully-formed from the head of her father, Jupiter, to the Biblical creation of Eve from Adam’s rib; from the Yiddish legend of the golem, the elemental and indestructible humanoid who both protected its creator and represented his primal self, to the Gothic cult of the vampire, the everlasting undead. Its present avatar—that of cloning—represents a form no more, or less, bizarre than many others it has earlier taken.

The fatal flaw that lies at the heart of this recurring allegory is that it chooses the inescapable prison of eternity over the irrepressible freedom of the infinity of life in its untrammelled diversity—and its necessary transience. Death is the mother of beauty, said the poet. The abyss, which lies beneath the nectar in a sieve, makes each drop as it falls into oblivion sweeter and more dazzlingly golden than all the eternally unchanging, eternally barren riches of Midas.

Jug Suraiya

Writer, columnist and author of several books

jugsuraiya@gmail.com