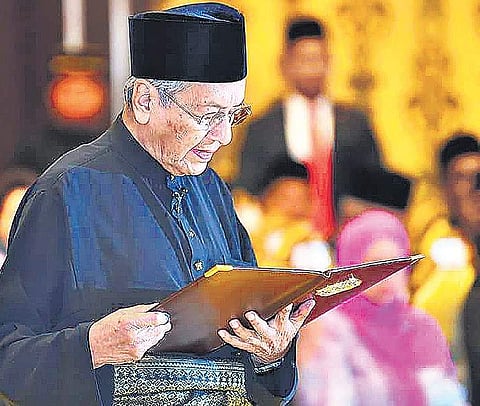

When Mahathir bin Mohamad speaks, at least Asia listens, if not many others. As incumbent Prime Minister of Malaysia and senior-most political personality in Asia, Mahathir’s recent election as Malaysia’s leader at the age of 93 brought some inherent wisdom of the ancients to the emerging Asian strategic scenario. Speaking in China, he accused his hosts of securing influence through debt-funded infrastructure that recipient countries could ill-afford. Five years ago when China initiated its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) to expand its outreach through investment in infrastructure, it was well known that China’s interests were not economic alone but essentially centred on garnering strategic influence in nations that it was investing in.

Save India there is barely a country from South to South-East Asia that has not been tempted by China’s cheap credit which was available from its overheated economy. Developing countries are usually stuck in the trap of low available internal funding for infrastructure, leading to compromises in development. That is why China’s BRI appeared to make immense sense. What was certain was that the Chinese were tough negotiators and extremely secretive. The terms and conditions of most of the BRI projects have not been transparent.

It started with Sri Lanka where the port of Hambantota in the south was developed as a virtual greenfield project at a very heavy cost. That forced Sri Lanka into ‘debt for equity’ arrangements leading to the Chinese taking over operational control. Mahathir’s predecessor Najib Razaq had similarly negotiated projects and for some period of time Malaysia appeared to be making the most of China’s goodwill. For China, Malaysia is a very important nation.

Presence of ethnic Chinese population apart, it is geo-strategically located in proximity of the South China Sea (SCS) and controls some crucial sea lanes. Mahathir’s unexpected return to leadership role led him to question the prudence of the infrastructure contracts and the terms and conditions. This has placed $40 billion worth of Chinese projects under scrutiny. Mahathir has also re-raised the flag of resistance to militarisation of the SCS.

This could be the spark which either directly forces other recipient governments to re-examine the investments and the terms and conditions or the same is forced on them by sheer domestic pressure. The man who should be really worried is Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte whose actions have been akin to former Malaysian Prime Minister Najib. A strategic sell-out of Philippines and its interests has been the norm.

A possible political backlash against Duterte may well force him to recalibrate his strategy. A survey did indicate that 9 out of 10 people from the Philippines want Duterte to negotiate back some of the islands in SCS, now occupied by China. A whopping $ 24 billion promised as investment has not fructified leaving Filipinos very angry.

If the results of the elections in the Maldives is any indicator then China will need to revamp strategy considerably and even outside South East Asia. Abdullah Yameen, out and out a Chinese protégé, lost the election by a fair margin to a dispensation under Mohamed Solih known to be pro-India. Yameen’s reversal of Maldives foreign policy to one openly in support of China may have been one of the contributory factors which led to the victory of Solih. If we are to believe this then the resistance to Chinese hegemony may gain traction faster than can be predicted.

Nations such as Indonesia, Cambodia and Laos could follow suit, especially if traditional investments from the US and Japan are to materialise. Fortunately for China just when the opportunities seem to be rising for the US, President Donald Trump has decided not to attend the ASEAN summit on November 11-15; a strategic opportunity lost. Will vice-president Mike Pence’s presence make up for it?

Coming to the western neighbourhood, Pakistan is the biggest recipient of the Chinese largesse, or so it seemed till recently. It is reliably learnt that the $62 billion-plus China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) is no longer receiving the same smiles from the Pakistanis as it was three years ago. The jobs have all gone to the Chinese, including labour. Chinese colonies coming up in urban areas are being frowned on and a culture mismatch with invasion by thousands of Chinese is causing social worry.

Besides, a $4 billion annual debt servicing from 2019 onwards is something Pakistan can ill-afford, meagre as its foreign exchange reserves are. To top it, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo had earlier threatened that for any economic bailout from the International Monetary Fund, Pakistan will have to make transparent the terms and conditions of the CPEC; none of the debt servicing would be permitted from the funding made available by IMF. So another chink in China’s ‘infrastructure diplomacy’ appears in the making. It could lead to another ‘debt for equity’ situation enhancing Chinese presence. Pakistan is far too close to China for its strategic needs but this could force it to be more balanced in approach just as many others have learnt in South and SE Asia, the hard way.

Lt Gen (retd) Syed Ata Hasnain

Former Commander, Srinagar-based 15 Corps

atahasnain@gmail.com