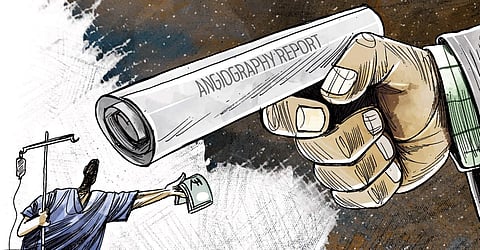

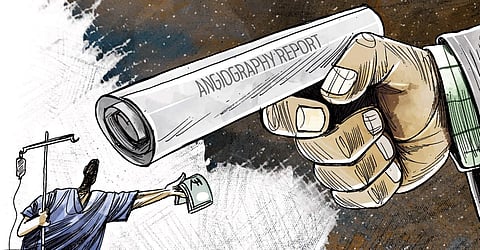

Medicine is flying blind. Thousands of medical journal articles are published every month on potential new treatments and diagnostic tests. Precious few of them measure how well doctors are doing in the real world, outside of controlled trials—what they are doing right, what they are doing wrong and what they are forgetting to do entirely. No wonder our medical system wastes billions of dollars a year,” writes Mathew Herper of Forbes. Last week, The Outlook published an extensive article on angioplasties—the procedure to remove blocks in a blood vessel—and their hazards. Most of what they wrote about was the cost of the stent—a support placed inside a blood vessel to remove blocks— and its abuse. Little did the article touch upon the crucial point: The coronary angiogram, the test to find if arteries are blocked, the main villain in the piece.

I had written about it and have been doing so even before some of the leading American researchers like Harlan Krumholz came on the scene. The only area where angioplasty has a proven track record is during an acute heart attack and during such times also, the procedure has to be done within minutes. Rest of the time, it is done just to make money by frightening patients and their relatives saying that there are blocks in the coronary arteries (vessels that supply blood to your heart). Almost every human being, including children, have one, two or, even three vessel blocks. This was shown in the post-mortem angiograms done on 205 young American soldiers shot dead in Vietnam and Korean wars.

So almost all our angioplasties are unnecessary. The blocks in fact do not usually critically restrict blood flow to the heart muscle. If the doctor studies the FFR (Flow Fraction Ratio) across a block, almost 90 per cent of the so called critical blocks become benign to be left alone. To my knowledge, no hospital in India does the FFR although they do sundry tests for money. In essence, the only indication for an angioplasty is immediately after a heart attack— if the vessel blocked is the one causing the attack. Treatment is better. Asymptomatic patients have no indication for an angioplasty at all. Coronary artery blocks aren’t synonymous with coronary artery disease. Therefore, the angioplasties and exorbitant costs to patients can only be curbed if routine angiograms to diagnose coronary artery disease are banned! In 1991, a Harvard group under Professor Bernard Lown had shown that a moratorium on coronary angiography alone can save patients from greedy cardiologists. Tom Treasure, an aggressive cardiac surgeon, made this plea in the medical journal, The Lancet. The scientific role for angiogram is only when the patient’s clinical assessment demands either an angioplasty or bypass surgery for relief from chest pain. Legislations to control the cost of stents will not help patients who are exploited through unnecessary angiograms for diagnosing coronary artery disease. The government should make audits mandatory for such procedures.

For corporations, the idea that “you can’t manage it if you can’t measure it” is an old chestnut. General Electric, Toyota and other companies have had data-driven qualityimprovement efforts for years. But medicine—supposedly a more scientific profession— has been slow to measure itself. Krumholz is one of the handful pioneers pushing to do this. There are many other reasons to work on banning diagnostic angiograms in asymptomatic patients. The faster, the better.

Modern medicine abounds in dogmas: many procedures are not scientifically audited. Every hypothesis is true until refuted by new ideas. Today, knowledge in the medical field is replaced by information. Thus, doctors rely only on data and not wisdom. The so called evidence based medicine is really evidence burdened.

So, it is time to audit all the technologies used in patient care just as we have placebocontrolled trials for drugs before releasing them for human use. Even in the case of drugs, in some rare instances, release of drugs before being audited by such trials had resulted in major damage resulting in their withdrawal. We should debate the issue of auditing untested technologies like angiograms.

For example, the unmeasured physiologic effects of indwelling catheters—a tube used to remove fluids from the body. The Swan-Ganz catheter was introduced without appropriate validating studies to compare with identical groups without the catheter. This catheter by itself could be an adverse factor for many critically ill patients. (Spodick DH the Swan-Ganz catheter. Chest 1999;115:857-858).

Coronary artery surgery is the next popular surgical procedure crying for proper audit. There was a demand for audit in this area way back in the early 1970s, indeed all new surgical procedures are better audited by controlled studies before being routinely performed in practice. (Spodick DH. Revascularization of the heartnumerators in search of denominators. Am Heart J 1971; 81: 149-157)

Writing a balanced editorial, Harlan Krumholz from Yale laments: “In a fee-for-service system, cardiac procedures generated billions of dollars in revenues each year. A high volume of procedures brought prestige and financial rewards to hospitals, physicians, and the vendors of medical equipment. In this environment, the US health care system rapidly produced and expanded the capacity to perform cardiac procedures and training….This increased capacity may also have fuelled demand for procedures.” This menace is spreading to other countries, more so to the developing countries in a big way where the auditing is non-existent.

Prof B M Hegde

Cardiologist & former vice chancellor of Manipal university

Email: hegdebm@gmail.com