The National Green Tribunal recently chided the Union government over the shoddy implementation of projects under the National Mission for Clean Ganga (NMCG). The well-intentioned and long-overdue initiative to clean River Ganga is no doubt ambitious, difficult and complex. The mighty Ganga, which has shaped the history and culture of the subcontinent, is now one of the most polluted rivers in the world. Originating from the pristine Himalayan glaciers, Ganga gets polluted by callous and pervasive human interventions that fill it with toxic contaminants and organic waste.

The river is smothered with biological wastes, industrial effluents and inestimable contaminants spewed by thoughtless rituals in the name of religion. Thousands of unauthorised outlets from hospitals, factories and businesses that dot the riverfront in hundreds of cities and towns continue to pollute the river with brazen indifference. What has invited the critical comments of the Tribunal is the escalation of pollutants even in the relatively cleaner upstream stretch between Haridwar and Unnao, where the water was found to be unfit for drinking and bathing.

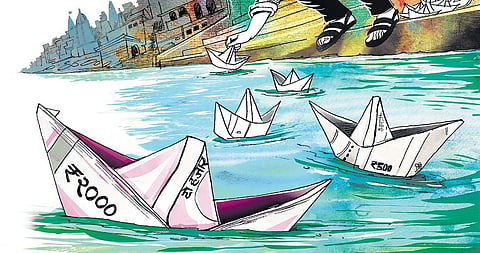

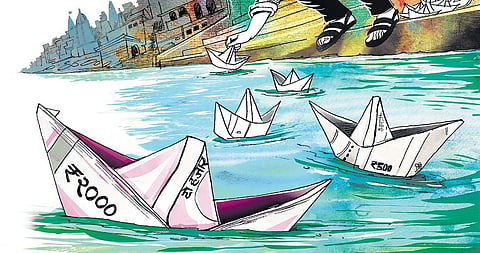

A mind-boggling 12,000 million litres per day (MLD) of sewage enter the river. The real volume will far exceed this official estimate. The existing treatment capacity along the river is 4,000 MLD. It is reported that 94 treatment plants, which would treat 1,900 MLD, are under various stages of implementation. These facts convey a bleak picture of the imperfect execution of the Mission. Blaming the ministry, technocrats and officials does not serve any purpose. It will not salvage the project or provide useful tips for the future. Even if all sewage treatment plants are commissioned, Ganga will still be polluted. It is not cynicism but pragmatism that forces this observation. Expectations are naturally roused when grandiose ideas enter mainstream political discourse. But they are often belied.

Except for a few instances like the Delhi Metro, Konkan Railway and such handful of projects, great expectations have always fallen by the wayside due to delayed and imperfect execution. Why does this happen often? The political executive at the national and state levels, regardless of their ideological proclivities, are not bereft of ideas.

And in the pious hope of translating these ideas into accomplishments, megaprojects are launched with unmistakable fanfare, only to be mutilated later. The most common cause behind this is the mismatch between ideals and reality. In the enthusiasm about the glorified outcome, ground realities like social resistance, procedural roadblocks, fear of the bureaucracy (real and perceived) and the consequential hyper-caution, and lack of ownership by the public are often ignored. Lack of social ownership renders stakeholders into spectators.

And spectators are quick to find fault and protect their self-interests. Equally pertinent is the inability of experts (aka consultants) to fathom the diversity of social, political and economic dynamics that have the potential to stall or derail projects. Textbookish ‘threats and weaknesses’ identified in their SWOT analyses are often thrice-removed from reality. In short, their ‘science’ is sound but the execution is flawed. The political leadership, in its eagerness to achieve results, is swayed by such ‘expert advice’ only to realise projects invariably develop unforeseen problems and turbulence. Lack of adequate homework and unrealistic optimism coupled with the perceived political benefits of premature launch are the endemic causes of fatal project failures.

And that explains why governments cannot resist such temptations either. The inability of policymakers and techno-bureaucrats to evaluate a project from the point of view of ordinary citizens has been another major blot on our development experience. Otherwise how do we explain ‘people’s resistance’ against development projects designed and implemented by the ‘government of the people?’ Stakeholder discussions have been reduced almost to the level of farce with powerful interests hijacking such consultations. Let us admit that the Indian state has not been able to keep aloof from such powerful forces and align with the powerless and silent majority. So consensus is manufactured which will naturally be short-lived. It cannot be denied that the Indian bureaucracy has rich and varied experience and understanding of the complexities of project execution.

They may be strangers to the latest tech (unlike the consultants) but technological and drawing-board knowledge cannot accomplish results unless tempered with administrative realism. Grand ideas espoused by the political executive have to go through this process of technological and administrative validation. Social connectivity, participation and ownership have to be real, not cosmetic.

The bureaucracy should have the humility to listen to the weakest citizen with due importance. Sadly, arrogance and presumptiveness occupy the chairs reserved for humility and accommodation. In a complex project like Namami Gange, the importance of stakeholder consensus and commitment cannot be overemphasised. Though some funds are apparently earmarked for this, half-hearted and mechanical stakeholder consensus-building will not yield results.

The moment cleaning Ganga is reduced to an officially-driven programme, its fate is foretold. The ideal of accomplishing a Clean Ganga should have galvanised millions of Indians irrespective of religious, economic and regional differences. Evidently such a dream has not yet dawned on the administrative psyche. Perhaps such an ideal of a national consensus in a fissured polity like ours is far-fetched. Without that most crucial prerequisite, all the money available for the project cannot clean the sacred river. And once every Indian hopes and believes with pride and optimism that one day Ganga shall flow with its fabled purity and divinity, nothing can stop from that dream becoming a reality. Doesn’t the mighty river that nourished our forefathers deserve such a homage?

K Jayakumar

Former Chief Secretary to Government of Kerala and currently, Director of Institute of Management in Government at Thiruvananthapuram

Email: k.jayakumar123@gmail.com