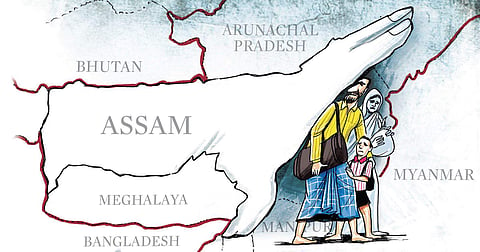

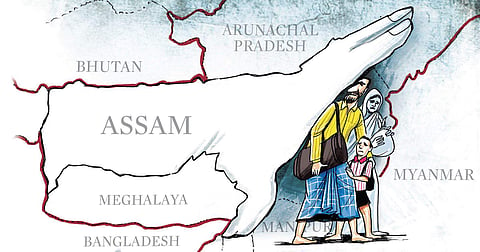

The National Register of Citizens is a process that has not just the mandate of law, but also of political opinion in Assam. After all, who wouldn’t like to know how many illegal immigrants are around, especially after decades of turmoil over the issues of illegal settlers and ‘Bangladeshis’.

When the NRC exercise began, many hoped it would finally lay decades of fatigue, bitterness, harm and suspicion to rest. What has happened has created more confusion even as credible reports emerge of land being acquired for purposes of a detention camp in Goalpara district, even as the home minister declares no one will be placed in detention camps.

Everyone in Assam wants a clear NRC. But the process has been mired in confusion from the start and created acute tension. This is not the way it should have been done. Upholding the law is one thing, but the technicalities of law cannot be divorced from facts on the ground.

Let me cite a few cases of which I have personal knowledge:

● A relative who happens to be married to a Muslim man of Assamese lineage—the entire family was off the list because there’s a discrepancy in the spelling of his grandfather’s name between the record and the application.

● Another friend found herself on the list, but her adult sons and one daughter-in-law off it (now all of them are on it, but the cook is not).

● Prof. Monirul Hussain, formerly of Guwahati University and now holding a chair at Jamia Millia Islamia in Delhi, a top scholar and as Assamese as they come, found himself summoned to Guwahati for verification of his identity. Prof Hussain has spoken of this publicly and the sense of humiliation and hurt that it caused to a teacher of decades of scholarship.

● There are others, in my family, who are on the list and who haven’t had a problem.

So it’s a mixed record of inefficacy and correctness.

That is why the Supreme Court’s decision to extend the deadline till December 15 to file contestations to those who are out of the list and re-allowing five documents including the 1951 NRC is not just welcome but critical to clearing the clouds of confusion. But the number of those earlier excluded who have filed for their inclusion is but a trickle of the 40 lakh shut out of the list and officials hope this will speed up. However, my view is that not less than six to 12 months should have been provided for examining details and cross-checking references.

In addition, the NRC is afflicted by discrepancies and factual inaccuracies that have crept into name spellings as also the family lineage, which are critical to the establishment of identity. Parents are on the list and children are not, or vice versa. As far back as August, recognising such concerns, the Supreme Court ordered a pilot project on re-verification of 10 per cent of the people in Assam who were excluded from the draft NRC. It is to be noted that is staff at the lowest rung, data operators at NRC centres, are key as they control passwords and access to personal data.

Going by the statements of various political leaders, there is a profoundly mistaken and widespread perception that the 40 lakh are illegal immigrants—this is incorrect. There are illegal immigrants, but having researched the issue in Assam, the rest of the Northeast as well as in Bangladesh, my view is it is likely to be far less. This can be partly explained by the changing pattern of out-migration from Bangladesh as its domestic economy improved, decreasing the attraction of a risky trip away. However. movement still continues out of the country to West Bengal and from there to other parts of India as migrants seek to cross into Pakistan, reach the Middle East and even Europe. They also take perilous journeys to Thailand and Malaysia and even Indonesia on risky vessels.

In all of this, it is worth noting Bangladesh’s position—a senior retired military official wrote that the exercise of detection and possible deportation from Assam was a security threat to his nation. An adviser to Bangladesh’s PM said Sheikh Hasina had been assured by none other than PM Narendra Modi that the NRC would not be an issue.

What can be done after the tumult has died down and the process of claims, counter-claims and judicial challenges is over—which could take years? We can rule out deportation as there is no deportation agreement with Bangladesh. Only those recognised as Bangladeshi nationals by their diplomatic missions can be sent back. The proposal of detention camps represents a failure of due process and an assertion of arbitrariness. It would lead to national and international opprobrium.

One option is the disenfranchisement of those of voting age from the non-Indian category. But again, this cannot be held in perpetuity for it would institutionalise statelessness, which is unacceptable. India’s experience of handling statelessness is poor, whether it is accommodating Sri Lankan Tamils or Bengali Hindu refugees of Dandakaranya or the Chakma/Hajong refugees (the second and third groups from East Pakistan, now Bangladesh) who landed up in Arunachal Pradesh. At most, such disenfranchisement can be done for a decade or so as was Assam’s experience with the Bengali Hindu refugees who fled East Pakistan between 1966-71 and defined in the Assam Accord of 1985.

I had designed a Work Permit regime about 20 years ago to enable a regulated labour flow into Assam of people who would be permitted to stay for a maximum of two years and would not be allowed permanent settlement, access to vote or citizenship. They could access healthcare, education, labour rights and repatriate funds home under a special arrangement. Of course, it never went beyond the National Security Advisory Board!

Today talk of Work Permits has emerged in Assam—but it cannot be a panacea for depriving people of other rights. If Indians are deprived of their rights through the NRC, it would show the process as flawed and unacceptable.

Experience of border-crossings and migration patterns worldwide show detection and deportation is most effective at the border. Over 3,000 km of the Indo-Bangladesh border of 4,096 km is already fenced. However, there are extensive marshes, rivers, streams and sandbanks where fencing is difficult. Once migrants slip in, the process becomes complex and wrapped in legal knots as the experience of Assam shows. Border management is key, with investments in better intelligence as well as infrastructure such as sensors to detect physical movement.

Sanjoy Hazarika is International Director of the Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative (CHRI), commentator and author. His most recent book is Strangers No More: New Narratives from India’s Northeast. Views are personal.

Email: sanjoyha@gmail.com