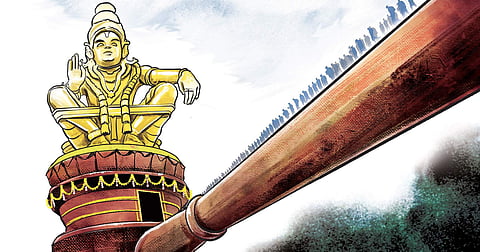

The country heaved a sigh of relief after the Sabarimala temple of Lord Ayyappa in Kerala closed on Monday at the end of a five-day ritual without any mishap despite the palpable tension on the subject of entry of women in the age group of 10 to 50 into the ancient shrine. Now everybody is thinking about next month, when the shrine is slated to reopen for a three-month pilgrimage season in mid-November.

In a recent 4-1 judgment, a Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court, consisting of then Chief Justice of India Dipak Misra, Justice Ajay Manikrao Khanwilkar, Justice Rohinton Fali Nariman, Justice Dhananjaya Yeshwant Chandrachud and Justice Indu Malhotra, overruled a Kerala High Court order, and lifted a traditional ban on the entry of menstruating women into the Sabarimala temple.

The devotees follow a vrata (penance) for 41 days prior to the pilgrimage. The vrata begins with the donning of a special mala made of rudraksha beads. The penance requires following a lacto-vegetarian diet, being celibate, going off alcohol and controlling anger during the period. They also see everything around as Lord Ayyappa, bathe twice a day and visit temples regularly.

In short, a devotee’s pilgrimage and what comes before it are no picnic. These practices are born out of ancient traditions, and are beyond the comprehension of the uninitiated.The court also ruled that the devotees of Lord Ayyappa are not a separate “religious denomination”. The verdict came just days before the opening of the temple of the “perennial celibate” for five days from 18 October. The only dissenting view came from the woman judge Indu Malhotra.

The court held that “the heart of the matter lies in the ability of the Constitution to assert that the exclusion of women from worship is incompatible with dignity, destructive of liberty and a denial of the equality of all human beings. These constitutional values stand above everything else as a principle which brooks no exceptions, even when confronted with a claim of religious belief.”

Justice Malhotra, in her dissenting verdict, said, “The equality doctrine enshrined under Article 14 does not override the Fundamental Right guaranteed by Article 25 to every individual to freely profess, practice and propagate their faith, in accordance with the tenets of their religion.”

“Constitutional morality in secular polity would imply the harmonisation of the Fundamental Rights, which include the right of every individual, religious denomination, or sect, to practise their faith and belief in accordance with the tenets of their religion, irrespective of whether the practise is rational or logical.”

Justice Malhotra also said that a “pluralistic society and secular polity would reflect that the followers of various sects have the freedom to practise their faith in accordance with the tenets of their religion. It is irrelevant whether the practice is rational or logical. Notions of rationality cannot be invoked in matters of religion.”

In this case, the “manifestation is in the form of a Naishtik Brahmachari. The belief in a deity, and the form in which he has manifested himself is a fundamental right protected by Article 25(1) of the Constitution.”

She further said, “What constitutes essential religious practice is for the religious community to decide, not for the court. India is a diverse country. Constitutional morality would allow all to practise their beliefs. The court should not interfere unless if there is any aggrieved person from that section or religion.”

Soon after the verdict, thousands of women took out rallies protesting against the verdict in many parts of the country. The Kerala government, however, has ruled out filing a revision petition before the apex court and said women devotees will be given protection to enter the 800-year-old temple.

Since Sabarimala’s Lord Ayyappa is a Naishtik Brahmachari practising the severest form of celibacy, he keeps away from the company of women. The temple ban on menstruating women is also in keeping with the wish of the deity, who is believed to have laid down clear rules about the pilgrimage. In the wake of the apex court verdict on this vexing subject, it is pertinent to ask whether courts are equipped to decide on matters of faith. And what the implications are if the paradigm enshrined in the verdict is taken to its logical conclusion and extended to other faiths.

Can the courts ask why Catholic women are banned from becoming priests and solemnising weddings? Or why Muslim women cannot become muftis or say namaz along with men in mosques?

Obviously the apex court resents Lord Ayyappa feeling shy about seeing menstruating women. In Hinduism, God, in the form of any symbol or statue, is a living being. The Lordships are silent as to what happens to Lord Ayyappa’s right to not see someone. According to the court, He cannot exercise any such discretion.

It is best for the courts to leave matters of faith alone. However, the system (including Parliament and courts) has to work for the elimination of social practices inconsistent with modern values.

For example, sati, which was prevalent in India, has since disappeared, thanks to social reforms and laws passed against it. Similarly, dowry, child marriage and infanticide of girls have been banned by the government. And it was the same with triple talaq.

Balbir Punj

Former Rajya Sabha member and Delhi-based commentator on social and political issues

Email: punjbalbir@gmail.com