Ancient and connected with nature, the folk music tradition of Western Odisha is unique in more ways than one. Gifted folk musicians from across the region, many of who are in their 60s and 70s, have

formed ‘Adi Dhun’ – Odisha’s first folk music band – with an aim to preserve this dying traditional music culture.

Bringing them together is 36-year-old Bhubaneswar-based folk dancer and researcher Rabi Ratan Sahu, who has been working towards rekindling people’s interest in the fading folk musical instruments

and bringing them to the mainstream.

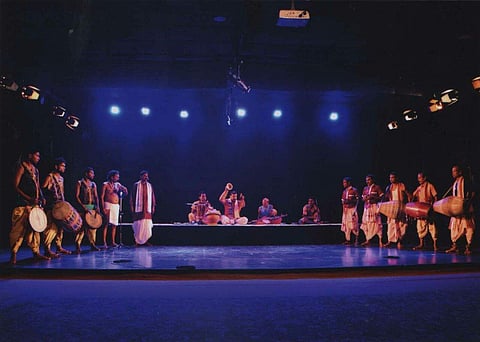

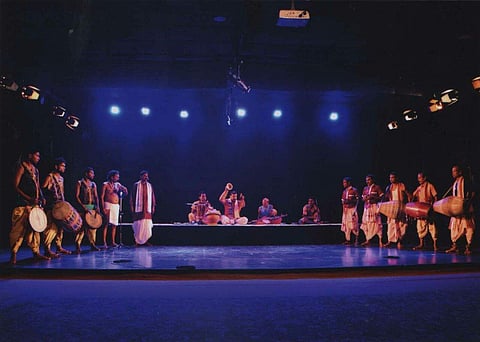

The band comprising 25 folk artistes recently performed in Bhubaneswar at a music festival hosted by the Indian Council for Cultural Relations (ICCR) and Culture Department. Their oeuvre included

instrumental music and songs weaved around nature and folk tales. While each artiste played a folk musical instrument, sounds of which are rarely heard today, together they performed traditional songs that are intrinsic to the cultural fabric of Western Odisha – be it child birth, a new season, rains, crops and even death.

Sahu, a recipient of Ustad Bismillah Khan Award, has always been fascinated by the sights and sounds of folk musical instruments. Having started his journey into the genre a decade back with research

on folk art traditions of Odisha from the Guru Kelucharan Mohapatra Odissi Research Centre, Sahu has collected some of the rare traditional and folk musical instruments from different parts of the State in the last five years. “Adi means ancient or first and Dhun means rhythm. These folk music instruments have been associated with folk cultures through their rhythm or music since ancient times. Since long, the folk music instruments have remained an integral part of the folk cultures of Western Odisha. Around 80% of all the folk music instruments that are or were used in the State have originated from Western

Odisha. However, with advent of modernity many folk music instruments are lost and some are on the verge. So to resuscitate these instruments and restoring their lost glory, I formed this folk band along with the musicians,” Sahu says.

He travelled across villages of Western Odisha to find out folk musical instruments that have either become extinct or are on the verge of extinction. Along the way, Sahu met musicians, many of whom are now a part of the band that he put together in 2017 with the help of Central Sangeet Natak Akademi. His motley group of musicians includes 78-year-old Alekh Sahu of Bargarh, who has been playing Sanchar Mrudanga for the last five decades. While Alekh is the oldest member of ‘Adi Dhun’, the youngest is 26-year-old Ajit Badhei of Bolangir who plays Khanjani. “Our band includes some of the best folk musicians of the region, who are in possession of musical instruments that are rarely seen or heard today,” says Sahu.These instruments include Brahma Veena, Ghudka, Khanjani, Sarangi,

Dhunkel, Birtia, Bhalu Bansi, Aad Bansi, Kathi, Kubja, Jhanza, Singha, Todi, Mrudanga, Madala, Sanchar Khola, Dhol, Nishan, Tasha, Mahuri, Ghumura, Dhap, Bir Kahali, Dibi, Timkidi, Mati Mardala and Gopiyantra. Among these, the rarest are Bhalu Bansi, Singha and Brahma Veena, played by 56-year-old Nirmal Rout of Nuapada, 72-year-old Ananda Bag of Bargarh district and 48-yera-old

Repa Majhi of Sundargarh respectively.

“Bhalu Bansi is an instrument like the flute which produces sounds resembling roar of a bear when air is blown into it. It’s a large instrument, 2.5 ft in length, which is played by the cowherd community in Nuapada and areas bordering Bargarh and Chhattisgarh. They usually play it while grazing cattle to keep wild animals at bay in the forest. Traditionally, it is also played during festivals and marriage ceremonies by the community members,” informs Rout.

Similarly, Brahma Veena is played by a community of priest-musicians present in Bargarh and Bolangir districts, who do so to appease local deities. “Very few musicians in Sundargarh district have Singha

instrument with them today. It is made from the horns of Gayal and people have stopped making the instrument ever since government imposed a ban on killing the animal for its horns,” says Majhi. The musicians feel their art forms are dying a slow death as the new generation is not showing interest in learning them and government is doing precious little to preserve the folk culture.

Sahu, who has set up the Sambalpuri Folk Academy at Bargarh to preserve folk dance and music, feels fortunate to have found the traditional artistes for the band. Although, it took him a lot of time to

convince them to be a part of a formal band and showcase their talent throughout the country. He says repertoire of the musicians is vast and what they perform is just tip of the iceberg. “Their music may be raw but is pure and beautiful. This folk music culture needs support of connoisseurs and government to survive,” he adds.