COLOMBO: Despite the existence of a unified “Tamil” identity, Sri Lankan Tamil society is rent by caste inequalities and is dived into “Oppressing and Oppressed Castes.”

But issues thrown up on caste inequalities do not find expression in the public domain for a variety of reasons, campaigners for social justice and researchers say.

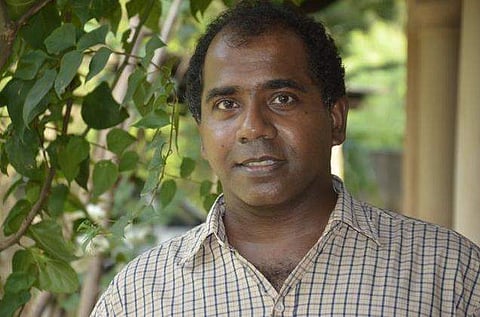

Basically, there is a lack of awareness among the oppressed castes themselves, points out Ahilan Kadirgamar, a Jaffna-based economist who is a member of the Collective for Economic Democratization. There is also no platform to air views which clash with the need to assert Tamil unity, he adds.

The Tamil struggle for territorial independence or autonomy has necessitated the sinking of caste differences among the Tamils in the face of unrelenting opposition from the Sinhalese majority which is perceived by the Tamils to be a united group so far as the Tamil issue is concerned.

Lastly and most importantly, there is a general de-legitimization of issues which are perceived to be injurious to “Tamil” nationalism. The Tamil intelligentsia and the Tamil media have a tendency to ignore or to discourage discussion on the internal problems of Sri Lankan Tamil society, especially caste inequalities. The 30 year long militant movement took an active part in suppressing the expression of caste discrimination even as it banned the grosser manifestations of discrimination.

As a hangover of the past, universities in the Tamil area do not encourage research on caste inequalities, Kadirgamar points out.

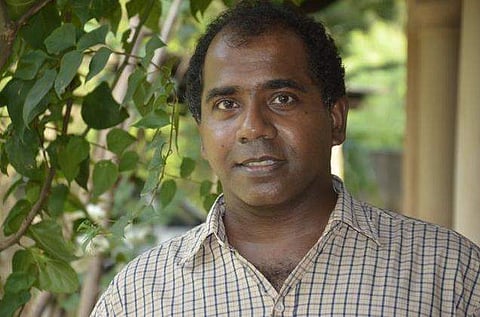

This is basically because Tamil nationalism, and the traditional and modern institutions of Tamil society, continue to be in the hands of the dominant caste of Vellalas, observers Murugesu Chandrakumar, former MP and now a campaigner for social justice. With the educational institutions in their hands, the dominant caste has captured the commanding heights of all modern institutions including those of the government.

Chandrakumar points out that only a tiny fraction of the elected representatives of the Tamils are drawn from the Oppressed Castes. Only a small fraction of the officer cadre of the 36,000-strong bureaucracy of the Northern Provincial Administration is drawn from the Oppressed castes. And this is reflected in the distribution of the government’s resources, he says. Chandrakumar related a case in which an Oppressed Caste man he had appointed as Principal of a school in Kilinochchi was removed by a dominant caste MP, the moment he lost his seat in parliament in 2015.

Kadirgamar says caste discrimination is reflected in the distribution of space in villages. The dominant upper castes occupy the best lands and the oppressed castes are given the worst. Some oppressed caste persons go to the Middle East as laborers but these come back with just enough to pay off their debts or build a house. There is very little evidence of social or economic mobility among the Oppressed Caste Gulf returnees.

However, thanks to the struggles between the mid-1960s and the mid 1970s, led by pro-Maoist Tamil Communists, the grosser forms of discrimination have ended. The right to enter temples and to eat together in public places were secured. But the struggle was not entirely peaceful. According to Kadirgamar, as many as 30 people were killed in caste clashes in a decade.

But the disappearance of the grosser forms of discrimination, has resulted in a lack of motivation to continue the struggle for social justice, Kadirgamar observes. Since there are no sentimentally touchy issues now, the Oppressed Castes have ceased to pay attention to their overall condition and seek remedies in tune with modern ideas of democracy, equality and justice, he says.