News has just come in that inequality of income, despite all the government’s PR noises, is at its highest since 1980; simultaneously, latest income tax department figures confirm the tax base remains narrow – only a minuscule number pays taxes and tax evasion continues to be rampant.

India’s top one per cent of income earners cornered 22 per cent of the national income in 2014, while the share of the top 10 per cent was a whopping 56 per cent, according to the World Inequality Report 2018, released in New Delhi last week.

In comparison, in 1983, when inequality was its lowest since the British introduced income tax records in 1922 in India, the top one per cent accounted for only six per cent of the national income, while the top 10 per cent earned 30 per cent of national income. Here’s the irony: the 1970s and 1980s was a derided period of low growth and political turmoil; but then equality was at its best with the bottom 50 per cent earning 24 per cent of national income and the middle 40 per cent just over 46 per cent, according to the report.

Myths Exposed

The Inequality Report, data also blows up some deeply held economic myths. One of them is that rapid growth and globalisation necessarily leads to widening inequality.

Lucas Chancel, an economist of the Paris School of Economics and one of the authors of the

report, points out that from 1950 to the 1980s, when Europe saw the fastest rate of growth, it was the bottom 50 per cent who were able to increase their income fastest.

The Inequality figures put paid to the ‘trickle-down’ theory, first advocated by American comedian and commentator Will Rogers, and practiced by Reagonomics.

It advocates a slew of tax breaks and financial support specifically for the creamy layer. It is assumed that the larger incomes accruing to the rich class will be astutely invested and will thus ‘trickle down’ and benefit the masses.

Is it, then, essential to boost the incomes of the top one per cent, who have seen the fastest growths in India, to ensure growth for the bottom 50 per cent? “The answer is ‘no’. It is possible to have high growth with low inequalities,” says Lucas Chancel.

There are also caveats put out that absolute poverty has ceased to exist, and poverty in India has declined with 140 million people being ‘lifted’ above the poverty line by 2011. But poverty and inequality are after all apples and oranges. The poverty base is defined so low – earning of Rs 26 for rural and Rs 32 for urban per day as compared with the UN benchmark of $1.25 a day (Rs 84) – that it does not test the quality of life.

Narrow tax base

On the other hand, the income tax department’s macro data shows just three per cent of the censused adult Indians filed income tax returns for FY16; and of these, just half or 1.6 per cent paid income tax; the others filed ‘nil’ returns. In fact, the share of direct taxpayers has been steadily dropping in the overall tax kitty since FY13 and in FY16 fell for the first time below half to 49.7 per cent.

India’s glaringly narrow tax base limits the ability of the government to redistribute wealth and fund infrastructure and fund crucial social programmes such as health and education.

There has to be some rethinking on not taxing agriculture income. It is not the 95 per cent of the poor farmers who benefit from the waiver. They earn less than the Rs 2.5 lakh a year, and therefore would be anyway outside the tax net. It is the rich rural folk – the 4 per cent of rural households who own more than 10 acres of land but account for 20 per cent of the country’s agricultural income – and the agricultural companies who benefit from the waiver.

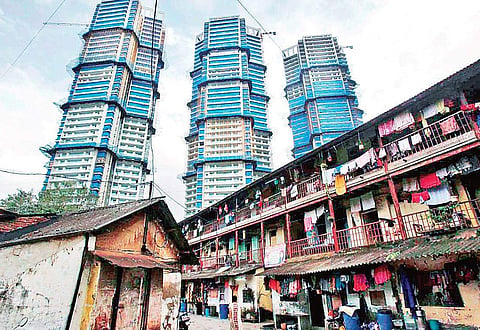

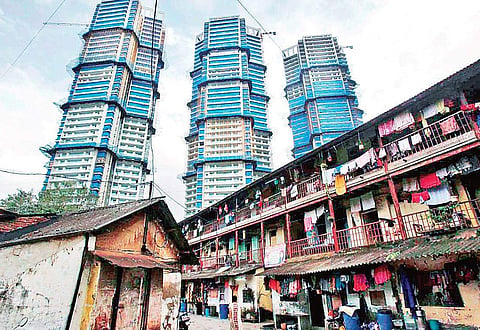

This was not the intended outcome. On the periphery of cities, thousands of these rich farmers trade their land to builders for crore; spending it on luxury villas and high-end SUVs without paying a cent to the government. The latest Inequality report should be treated with concern. Rising inequality is a threat to both growth and democracy. It is a threat to growth as it hobbles entire sections, and destroys their ability to compete and contribute their best. It is a threat to democracy as large swathes of the population find themselves marginalised from institutions of power, as the levers of decision-making go into the hands of those who best wield the power of money.

Defining Poverty

The poverty base is defined so low at an earning of H26 for rural and H32 for urban per day compared with the United Nation’s benchmark of $1.25 a day (H84)

gurbir@newindianexpress.com