For many stretches of storytelling, when the silence mingles into the sound of the humdrum, the camera simply stands and stares at the goings-on.

It’s not the way an outsider looks into a world he isn’t familiar with. It’s the look of ‘One Who Knows’.

Mrinal Desai’s camera is a quietly observant and an unobtrusively attentive entity in debutant director Chaitanya Tamhane’s amazing work of unalloyed documentation. And that’s the way it ought to be. This is a wise film that carries the knowledge of life, the burden of existence and the unbearable lightness of being on its shoulders without expecting to be congratulated for it.

Court scoffs at all classification. It is neither a “film” nor a “documentary”, neither all-knowing nor naive, it hovers in a sphere of utter unselfconsciousness, creating for itself the kind of narrative compulsions we have never seen before.

Nothing really ‘happens’ in Court. Nothing that would be considered cinematically defining or a moment of revelation that could be used as a screenshot at the awards functions.

Tamhane leaves behind all the things that they teach filmmakers in film schools and plunges into real life. Forget other courtroom dramas that you’ve grown up watching on screen. Tamhane takes us into a world that is so accessible it seems to exist in a realm that is the opposite of virtual reality.

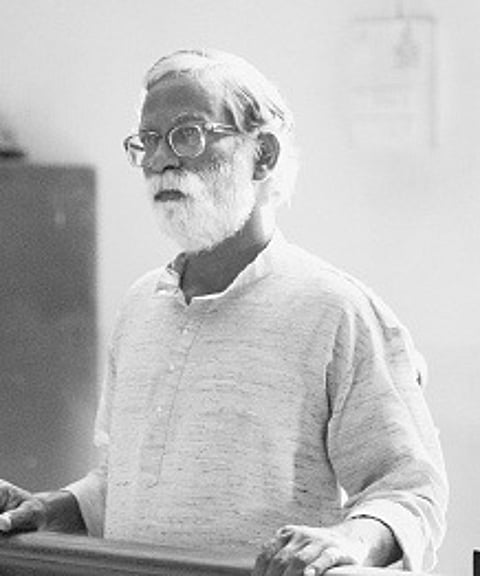

The story of an old street balladeer Narayan Kamble (Vira Sathidar) who ends up in the dock on charges of sedition is so bizarre, it can only happen in real life and certainly not in a film. That Tamhane actually films those pauses from real life where cinema cannot penetrate, is a measure of how innovative his vision is.Public prosecutor Nutan (Geetanjali Kulkarni) is a woman of steel whose face melts into unexpected housewifely gossip when discussing children and food habits with a female friend on the local train back home after a hard day of grilling and arguing in the session’s court. The understated perfection in the detailing of the public prosecutor’s household conveys a level of mastery over the medium where self-congratulation seems like a joke. This is the world we know and recognise and probably never associate with the heightened drama of cinema.

Leaving behind the rabble-rousing rhetorics of the best courtroom dramas — from B.R. Chopra’s Kanoon to Saeed Mirza’s Mohan Joshi Haazir Ho to Rajkumar Santoshi’s Ghayal — Tamhane’s Court creates a perfectly recognisable world of biases, prejudices, malice and inequality punctuated by rare bouts of compassion.

The film avoids Indians’ tendency of looking away from trouble. The court proceedings are seen through a series of hearings that capture the progressive futility of a system of governance that cannot see and hear the sheer absurdity of the bookish language, that is adopted with myopic directness.

While the narrative looks at the irony of an old decrepit man being tried for crimes that he has probably never heard of, it also looks at the lives of those sitting in judgment on Narayan Kamble’s life. The unvarnished beauty of this tale about the process of the law is that it doesn’t allow itself to get judgemental about the lives of the any of the people involved. It does allow itself the occasional smile, though.

At one point when the honourable Judge Sadvarte (Pradeep Joshi) yet again adjourns Kamble’s case, middle-aged woman Mercy Fernandes’ case comes up next. The judge, in all seriousness, refuses to Mercy’s plea (Mercy plea?) because — and I quote the honourable judge — “she wears a sleeveless blouse which is against the rules of courtroom behaviour”.

Oh yes, the judge too has his own life. And we see him on a holiday at the end of the film. A holiday that ends with a slap whose resonance we’ll hear for a very long time. Court is so true to life as to almost make us forget there’s a camera capturing the lives of normal litigators, lawyers and other tax-payers grappling with never-ending court sessions and the dreariness of everyday life.

The storytelling is stripped of all artifice to create the opposite of cinematic splendour. And yet, “Court” conveys just the opposite of theatricality. Nothing like this has been witnessed before in our cinema.

Court speaks several languages, many of them unspoken. Some of them unheard.