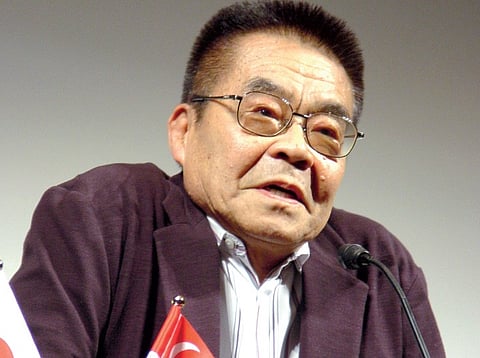

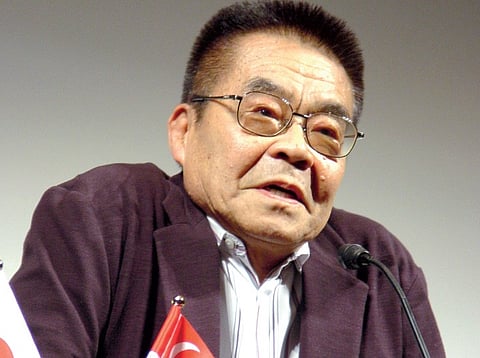

Yoshihiro Tatsumi was born on June 10, 1935 and died on March 7, 2015.

In the 79 odd years of his life, he wrote stories that included a motley crew of characters including garbage haulers with difficult mothers, sex workers with cloying fathers, over-involved window cleaners, petty scamsters and more. Yoshihiro Tatsumi was the grandmaster mangakka who crafted unsettling and unsentimental stories with such characters, and coined the phrase “gekiga” to describe the style of their telling. With his passing, he leaves behind an impressive body of work and a polite argument with Tezuka Osamu.

The Japanese, led by the West, are seen as consumers of some very weird entertainment. Much of this, like all good old-fashioned racism, has to do with their out-of-context caricaturing. Yet, one particular object of this mockery, which has more to do with the assumption that picture storybooks are for children, is the association of suited white-collar salaryman (the term for the Japanese man of business) reading comics on his commute to work.

In Japan, however, comics are not exactly adolescent picture books. They’re manga.

“Manga are not comics, at least not as most people know them in the West,” writes Paul Gravett in his book on the form. “The Japanese have liberated the medium’s language from the confining formats and genres of the daily newspaper strip or the 32-page American comic book and expanded its potential to embrace long, free-form narratives on almost every subject...”

Comic historians acknowledge that several factors predispose Japanese culture towards illustrated stories. There are classical art-forms like ukiyo-e paintings or netsuke miniature whimsical sculptures that combine object and story. The logogram-based Japanese script equips the mind to decode abstract symbolism that is the basic grammar of comics. However, all of this cultural heritage found expressive style and a phenomenal work ethic in a medical student named Tezuka Osamu — the father of manga.

Tezuka’s oeuvre contained a mind-boggling variety of characters and themes: from Astro Boy to Kimba the White Lion, as well as an eight-part biography — the famous Buddha series. However, Tezuka, working in the aftermath of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki, seemed to have an Asimovian project of re-connecting science to its humanitarian roots.

While the mid-1950s mainstream market in Japan was dominated by an obsession with Tezuka, taking advantage of the growth of a perpetually thirsty “red-book” press (these were the cheap comic book presses with their covers etched in gaudy red ink) and the rise of the cheap kashibonya rental library, a different breed of artist found a distribution channel and emerged from the shadows. They pushed manga towards an entirely new direction. And Yoshohiro Tatsumi grew to be one of the best known of them.

Gekiga—dramatic pictures — as opposed to manga was a noir film that inspired one to dive into the darkest parts of the Japanese soul. The social criticism of this school of artists and their wild popularity showed us that the Japanese, far from being some sort of child-robot hybrid, were more than willing to shine light into areas and subjects disallowed by the mainstream. Gekiga became a form of history and public education not told in school text-books. Later, Tezuka himself was inspired in Message to Adolf to borrow from Tatsumi’s playbook. The student had become the sensei.

Tatsumi’s thick autobiographical graphic novel A Drifting Life has been widely read in translation. His other work could be of use in another Asian country, where history is tightly repressed, the asking of questions increasingly banned and its mainstream entertainment dripping with nothing but sap and sentimentality. It could do with a bit of indigenous gekiga.

( www.zombiesandcomputers.blogspot.in)