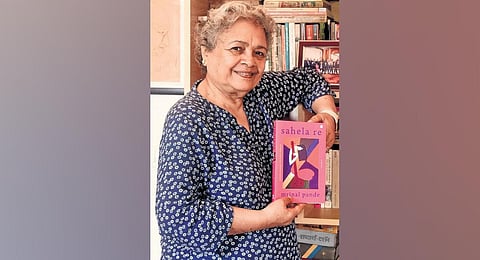

BENGALURU: Can you retrieve lost history if you chase it? Vidya Tripathi, the Delhi girl and the sutradhar of writer Mrinal Pande’s recently translated Hindi novel, Sahela Re (HarperCollins), was going to try. Vidya’s quest to seek out the sights, smells, gossip and insights of pre-Independence India’s musical gharanas and uncover the reasons for their decline is for a book.

It mirrors Pande’s search – a trained musician in Hindustani classical music herself – to understand the “great fracture in Indian society” from the 19th century, after the 1857 rebellion ending the dominance of the Mughal Durbar and Delhi’s hold on the arts, sending it to live or breathe its last, in the music rooms of north India’s small principalities.

“I began my formal music training under my first guru Dipali Nag of the Agra gharana in my thirties, standing at a cusp when this culture was all but gone,” says Pande. In the early 2000s, as the first woman chairperson of Prasar Bharati, she was also privy to the stories and the plight of musicians jockeying for a position in government-administered cultural institutions for survival. “Sahela Re is an attempt to record the last cry of a lost aesthetics, an art form, a way of life,” she says.

The epistolary novel captures the nomadic flow of life of women performers such as Hira Bai and her daughter Anjali Bai of Benaras and Husna Bai and her daughter Allarakkhi of Sherkothi close to Rampur. “Today, people say, ‘we go home after work and forget it all’, but for these women, their art form couldn’t be taken off as one does a ghungroo.

Their lovers, ustaads, children, patronage networks, all moved with them,” says Pande who knew artists Begum Akhtar, Kishori Amonkar and Naina Devi. In the novel, the shared confidences between singers and their closed circle, bound by unspoken codes and etiquette, carry the whiff of Pande’s personal encounters. “Nainaji once taught me seven bandishes in a day. When I said that I had come to her just to learn a few she said ‘Take now what I am still able to give….’ If you had limited knowledge of their music, you could be shown the door.”

As Pande’s protagonist travels around mofussils and cities and pries open closed doors to collect material for her book — old letters, photographs, records — she is a crusader for a lost cause. But there is no giving up. Vidya is the daughter of an upper-class north-Indian father. His orthodox views about women’s participation in private mehfils or public concerts, whether as artiste or audience, denied her mother a career; all of this makes Vidya’s search for artists of a disappearing world deeply personal. She regrets the place Bollywood music and Punjabi pop have in independent India and that technology is “destroying” the ecosystem of the old world by “liberalising” the borders of traditional music — these are also Pande’s own concerns.

“What Vidya is really after is to gauge how much of the old music is still left in the country. When I think of Vidya’s journey, I imagine her among Pompei’s ruins trying to piece together gaps in history and memory with broken mirrors,” explains the writer. Some of Pande’s short stories such as Bibbo have passing references to music.

For the first time, in Sahela Re, she has created a world in which the link between an artiste’s personal history and the production and circulation of her music and legacy are explored. The novel also considers those who practise the art of survival — Amaal, Husna Bai’s great-granddaughter, for instance, is part of a fusion group that performs in Brooklyn’s pubs—but passes no judgment.

Pande writes most of her fiction in Hindi. Sahela Re translated by Priyanka Sarkar in English, is also a memorial to lost languages. “The Hindi I grew up with used to be laced with Urdu, Awadhi, Braj Bhasha. The Hindi spoken now is linear and bureaucratic. It reminds me of what Kishoriji (Amonkar) told me once, of a dagger piercing her heart if she had to listen to even a single unmusical note,” she says. With Sahela Re, Pande has pulled off a rare book that is unsentimental even as it is marked by pain.