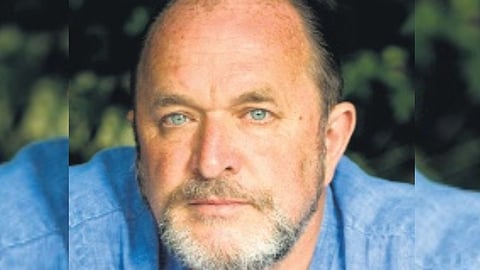

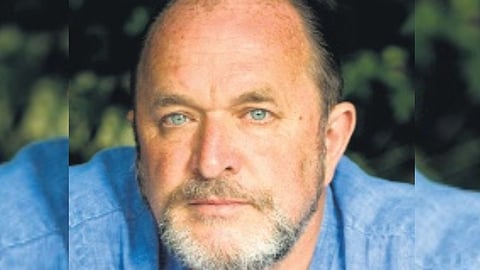

AT the recent launch event of his next book set to hit the stores in September, historian, curator and broadcaster William Dalrymple, in conversation with author Anirudh Kanisetti, unveils more than just the book cover.

As a counterpoint to the Silk Route, Dalrymple pitches the concept of a “Golden Road”, an Indian corridor of influence—“an Indosphere” that stretched from the Red Sea to the Pacific, down which travelled ideas that had a lasting impact on the world. Arts and artists, Indian religions, priests and monks, technology, astronomy, mathematics, and mythologies—all this will be part of Dalrymple’s literary caravan this time around in The Golden Road How Ancient India transformed the World (Bloomsbury), and they will be written up in his trademark style of history writing, one that is imbued with a sense of adventure, that has the pace of a novel, and through which new facts and people will come out of the cold.

The City of Djinns (1993) made his name but it was The White Mughals (2002) that made Dalrymple truly famous. His podcast, ‘Empire’ (2022), with journalist Anita Anand, had over five million downloads in its first six months. Each of his ten books have won numerous awards and prizes, including the Wolfson Prize for History, the Duff Cooper Memorial Prize, the Hemingway Prize, the Thomas Cook Travel Book Award and the Arthur Ross Medal of the US Council on Foreign Relations. Not a bad haul for “the last boy in class to go abroad”, as he describes himself on Wednesday before the audience at the British Council auditorium in Delhi to much mirth.

Being India-centric

As an author and the much-loved co-director of the Jaipur Litfest, Dalrymple, who now lives mostly in Delhi, writes history standing firmly in India’s corner. Even before the Silk Route, India was “the fulcrum” of the world, he says, adding that Marco Polo, the Venetian explorer who travelled through Asia in the 13th century, never mentioned the Silk Route in his accounts; it is China that runs with it, keeping itself at its centre. “And we swallow it, it’s just not historical. In classic conception and maps of the Silk Route, India is missing, which is nonsense,” he says to appreciative sighs from the audience.

He also points out that India’s economic heft is of an cient vintage; it was the main trading partner of Rome, then the rising power of the world. Kanisetti, the author of Lords of the Deccan: Southern India from the Chalukyas to the Cholas, offers another point of view: the give and take that makes nations and civilisations. He tells the audience that while trade with India may have funded Roman armies, the exchange “also fed into south India’s urbanisation”. Roman legionnaires or retired Roman legionnaires who stayed on in the south after being hired by local kings, helped build Buddhist institutions.

Radiating influence

An interesting disclosure of the evening was how Buddhism, one of ancient India’s first “exports”, extended its influence both in the realm of arts and ideas, and in the sphere of politics. Statues of Coptic saints [belonging to the Christian church of Egypt] had Gandhara chins [following the Gandhara style of art]. A Chinese Empress, Wu Zetian, was also receptive to Buddhist ideas and supported the establishment of Buddhism in China—this, Dalrymple admits, was due to political motivations, to beat down the Confucian establishment—making it, however briefly, the state religion. Hinduism’s passage in Southeast Asia was also due to the socio-political ideas it lent to other regions. For a millennium and a half, from 250 BC to 1200 AD, the “Indian takeover” was on the strength of sophisticated ideas, not a military conquest, he adds. Rulers of Java took from Brahmins, who had migrated there, the Hindu model of kingship; kings like Purnavarman cast himself as Vishnu on earth building large Vishnu temples to legitimise himself as god-king. Similarly, Dalrymple underlines his surprise at the many gigantic enterprises of temple building outside the Indian landmass. “The largest Hindu temple is not in India, but in Angkor Wat, a temple complex in Cambodia,” he adds. This Dalrymple book, like all his works, is likely to be interesting for its points of emphasis. He says at the launch, the text is going through the last tinkering. Will its final shape be any different than what he has been presenting? Will there be, to use the celebrated phrase, any scope of ‘a rescue of history from the nation’? On September 12, read to find out.