Cyanotype photography: newest in the analogue revival

The last few years have seen a revival of all things analogue. From vinyl records to polaroid photographs, the post-Covid years have awakened a need for something tangible – physical objects that hold our memories; objects that cannot be lost to cyberspace. Cyanotype photography, an alternative printing process first invented in the 1800s, is the latest in this wave, with Bengalureans trying their hand at making these striking blue and white photo prints. “In this age of digital photography and putting everything on Instagram, I feel like the hands-on process, and seeing the image on paper – that’s what is interesting to people,” says Greeshma Patel, an artist and photographer, who occasionally sells her cyanotypes, including a collection of shots of Cubbon Park, at pop-ups. “The minute they walk by my desk, and see the blue and white, everyone says, ‘Oh, this is so beautiful!’ I think there’s something about the blue and white colour schemes that is soothing and appealing to people, even though most of them did not know what cyanotypes are,” she adds.

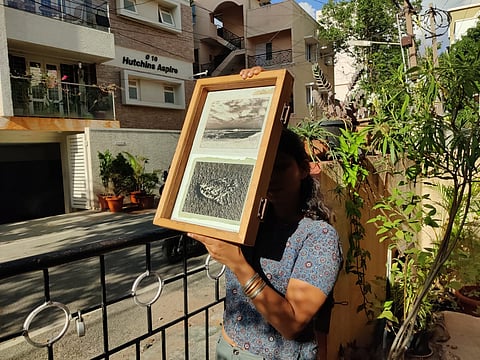

Workshops held regularly across art venues in the city teach both beginners and seasoned artists and photographers this easy-to-pick-up process that doesn’t require expensive equipment or a professional dark room like film photography does. Workshops generally involve teaching two methods of making cyanotypes – with digitally created photographic negatives that are printed out, placed on chemically treated paper, and exposed to direct sunlight; or using physical objects that have interesting shapes. “You can create something called ‘photograms’ by placing objects on a sensitised piece of paper which, when exposed to UV light, will give very interesting silhouettes and sometimes also render the translucence of the object in very interesting ways,” says Vivek Muthuramalingam, the co-founder of Kanike Studios, adding, “If people want to get into analog photography, they should perhaps try their hand first at making cyanotypes.”

The popularity of cyanotypes in recent years can partly be attributed to accessibility, says Mohit Mahato, the co-founder of Pagal Canvas Backyard, an alternative print studio in Sanjaynagar that hosts cyanotype workshops. He says, “Until recently, these chemicals were only available in chemical stores, and very regulated so they were not accessible for people to buy. With the growth of print culture and art colleges doing it more and more, these chemicals in diluted and mixed forms are being sold online – you can buy cyanotype photography kits now that have the chemicals, paper and detailed instructions on how to do it.”

Some enthusiasts in the city are making the best of this access and pushing the boundaries of cyanotypes beyond photographs and photograms, printing them on tote bags, postcards, sticker paper and even making animations out of them. “I’m not a photographer but I draw, so I thought, ‘what if I make negatives out of my drawings?’ I drew on 4×2 cm small transparent sheets of paper, 120 of them, I turned them into cyanotypes, took photographs of them and turned them into a short animation,” shares Radha Patkar, an illustrator. She adds, “If you mix up the proportions of the chemicals differently, or add another hue to it like coffee or tea, it’ll turn outdifferently… developing any image like that is a new surprise every time, that joy is what people love about cyanotypes and why it’s the new happening print-making method!”