BENGALURU: One, two buckle my shoe, three, four shut the door…We all know how it goes. But what are these one and two and three and four? As students, we learned that they are Arabic numerals. But we had learned wrong. If you rewind the chronicler’s tape a couple of centuries before the Islamic Golden Age (8th century CE – 14th century CE), you’ll find these symbols found their home in modest Indian allies by 6th century CE. And yet, most of the world and even most Indians err in its origin.

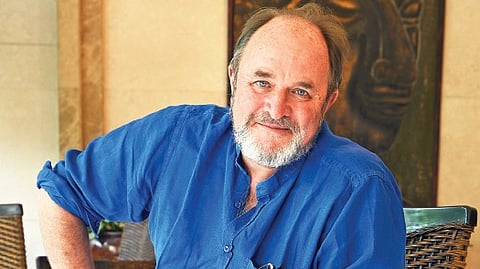

India-based Scottish historian and author William Dalrymple believes that it is because India has never been great at promoting itself. “I’m baffled by it, but it’s true. No one outside India knows names like Aryabhatta and Brahmagupta. But every single one of them will know about Pythagoras and Archimedes. People should look at why that is.

That’s one of the things this book is trying to do – make the case for this export of Indian ideas. The lack of which is why you get those WhatsApp forwards about nuclear weapons in the Mahabharata. People know this is a great culture. But they don’t have the raw information to flesh it out into facts. The true story is extraordinary. You don’t need to make anything up,” says Dalrymple.

The book he’s referring to is his latest, The Golden Road: How Ancient India Transformed the World (Bloomsbury, `999), discussing the ways India influenced Eurasia from 250 BCE to 1200 CE, in what Europeans call the Dark Ages. The ‘Golden Road’, the book argues, was a route through India that connected Eurasia. The Indian influence in the region is what he calls the ‘Indosphere’.

“The fact that Buddhism and Hinduism are all over the world is an example of Indian influence. It’s an empire of the spirit, which is much rarer than empires of the sword. Ideas passing peacefully by means of their sophistication and attractiveness is a rare story. In places like Singapore and Hong Kong, no one is offended when I talk about it.

When I was in Kuala Lumpur, there was a performance of the Ramayana in this Muslim city. Everyone knows that Angkor Wat was originally a Hindu temple. There are images of the Ramayana and the Mahabharata all over Southeast Asia. Everything I’m saying is hiding in plain sight,” shares Dalrymple.

The historian, who was in Bengaluru recently first came to the city in 1984. “I had just spent my 19th birthday night sleeping on a temple floor in Hampi with a sleeping bag. Then I woke up, walked across the banana grove, and jumped into the Tungabhadra river on the morning of my 19th birthday and caught a train to Bangalore. Back then, everyone seemed to have horses and stables. It’s a completely different city now but it’s very buzzy,” reminisces Dalrymple.

“Karnataka is one of the most underrated states in India with many wonderful sites near Bengaluru.” The book discusses in detail the Indo-Roman trade. So, when he learned about Roman coins being found in Bengaluru back in 1965, he was not surprised.

“India was the number one trading partner with the Roman Empire so much so that when Rome fell it led to an economic crisis here. One of the arguments in my book is that we’ve got to forget this idea of the Silk Road, which didn’t exist in antiquity but in the Middle Ages. Back then, Rome and India were principal trading partners.

People have been finding Roman coins since the East India Company reported finding them in large numbers around Madras (present-day Chennai) in the 18th century. I came across a report in one archive talking about someone who’d found seven coolies (laughs) of gold Roman coins, south of Madras,” he concludes.