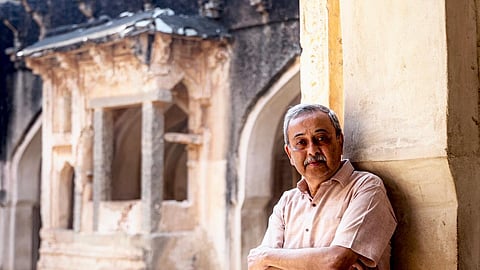

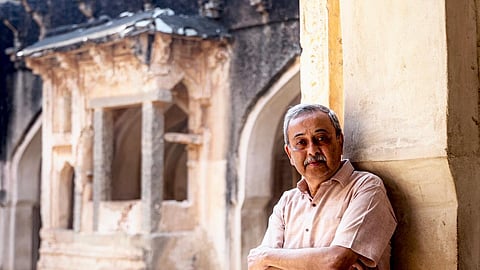

Riding his scooty into the ancient sprawl of Hampi, photographer Saibal Das let the wind, the light and the silence guide him, his camera always ready to capture the best shots. He moved by instinct, stopping whenever a shift in the sky or a glimmer on stone suggested that something was waiting to be seen. It was a relationship more than a project, rooted in a much earlier encounter.

“My first visit to Hampi was around 2001. Later, I felt the urge to return and truly look at Hampi. Whenever I had money to buy film and the weather looked favourable, I would fly from Kolkata to Bengaluru and take a train to Hampi. Then I’d come home, process the rolls and anxiously wait to see how they had turned out,” he says. That uncertainty, he insists, was part of how the place taught him to look.

When Hampi: The Rituals of Time was finally released at Raj Bhavan recently, the moment felt both surreal and grounding. It was also a moment shaped by the support of those who believed in the book’s quiet

power. Among them was parliamentarian Lahar Singh Siroya, who saw the project from vision to publication. His belief ensured that the photos Das took through the sun and monsoons would reach the right hands.

Das’ Hampi was never the Hampi of brochures. It was not the stone chariot repeated endlessly on social media or the famed pillars. “People asked me, ‘Where is the stone chariot? Where is the Vittala Temple?’ I would tell them that they have seen those things a hundred times and that there is so much more to look at in Hampi,” he recalls. What he sought was a more intimate conversation between stone, myth and time.

Across 700-800 frames, shot entirely on black and white film, Das searched for Hampi’s pulse. Standing behind his camera, he felt the place speak through stone and sky. “The ruins are full of energy and it was transmitted to me, helping me capture Hampi’s true essence,” he says.

He photographed what many others walked past. The riverbed of the Tungabhadra, carved into natural sculptures by water that had flowed thousands of years ago, textures on the walls of the Queen’s Bath that carried the weight of age, the marks of time and scratches left by modern visitors engraving their names. His frames were full of quiet presences – a dog beside a great crack in stone, a lone tree with a bird perched atop, a lamppost beneath a sky streaked by a jet’s fume, a woman in saree at

Kodandarama Temple, the quiet corners behind Vittala that most people never see. “One of the hardest shots was the lamppost with the jet plane’s fume. That was how I showed the presence of human beings, not just physical humans but their traces in today’s world,” he says.

His emotional connection with the site began years before he saw Hampi. As a teen, he had read a Bengali novel, Tungabhadrar Teere (1959) by Sharadindu Bandyopadhyay, a love story set on the river he would one day photograph. That sense of romance lingered in his frames, softening the hardest granite. Nature itself often intervened at the right moment. “There is a panoramic Bhima Dwara, where a cloud was passing and the one from Hemakuta Hill with a black rain cloud above the monument. Those two images feel closest to me,” he shares.

Another influence deepened his way of looking at Hampi. Das had long admired photographer Prabuddha Dasgupta, but encountering the latter’s work changed something fundamental. The starkness, the restraint, the way the late photographer allowed space and silence to speak felt uncannily close to how Das himself was beginning to look at the landscape. “When I looked at his work, it opened my eyes. Some of my pictures were influenced by Prabuddha. When I saw his pictures, I realised I was looking at things the same way he did,” he shares. If there is a single thread

that binds the book, it is devotion – to texture, to patterns, to silence and to myth. Above all, devotion to a place that kept calling Das back. Or as he puts it, in his own gentle way, “My love letter to Hampi lives in a few frames. Those moments feel deeply mine.”