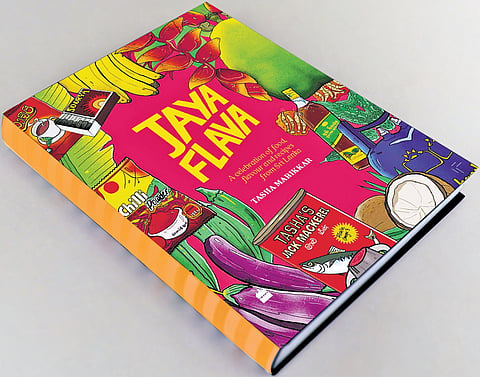

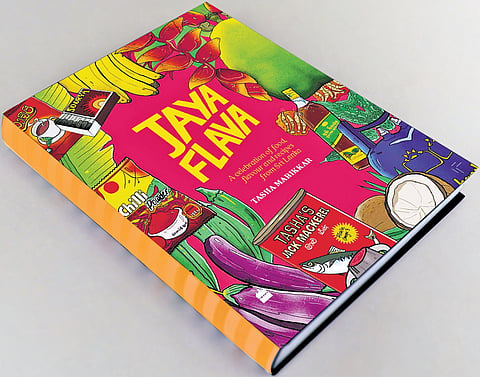

CHENNAI : In our adulting phase, living alone, managing expenses, and learning the daily grind of life, we have all missed our home-cooked comfort food at least once. We might have tried to replicate the recipe by taking guidance from our mothers or a cookbook. But what do you do when you don’t have enough materials to walk you through to make your favourite dish? You write your own cookbook. That’s what London-based Tasha Marikkar has done with Jayaflava, A Celebration of Food, Flavour, and Recipes from Sri Lanka.

The colourful, bright, hardbound book works as an encyclopedia of our neighbouring country giving the reader an insight into the different communities and their cuisine. “I want people to take away one key thing. Sri Lanka is an ethnically diverse country, and our cuisine is rich and has been shaped by the many communities that live there. Despite our bad press in the last few decades, food has always been our great uniter,” says Tasha.

Excerpts follow

Your first book on a cuisine close to your heart…

To say that I love Sri Lankan food would be an understatement; it became a passion for me while living in London and when I needed a recipe, there were no authentic recipes in any of the cookbooks I owned. I had a few cookbooks written by legendary ‘Aunties’ but their measurements are so hard to follow — some would refer to a ‘mundu’ of rice which is essentially an old can of condensed milk as a measure. These kinds of recipes are so open to interpretation, and it made it difficult to get a consistent outcome.

I also started to notice that a lot of people my age and younger in Sri Lanka did not know how to cook traditional food, and I knew, that if I did not try to record these recipes, the methods of cooking them would get lost over time. It became a personal mission, ensuring I preserved our key techniques and highlighted what made each recipe so special.

I had a lot of advertising jobs in London. There was one where I worked late nights and the only respite I had was coming home, cooking a comforting Lankan meal. It made me feel connected to my home and culture when I felt drained. Commuting after one long day, it hit me that all these recipes I was collecting should be shared.

Is Sri Lankan cuisine less explored compared to other South Asian countries?

Since the last decade, some light has been shone on Sri Lankan food, but not in the depth that it deserves. It is far less explored than other South Asian cuisines, and much less so when compared to Southeast Asian and East Asian cuisines. It might be controversial, but the Sri Lankan hospitality industry doesn’t fully understand the value of the island’s food; the flavour, the balance, and the health benefits that are huge. If you want to eat a good Sri Lankan meal in the country, it’s mostly in people’s homes and Colombo. Very few restaurants celebrate our cuisine. This is the systematic reason that a cuisine that has centuries of heritage has been largely undiscovered. Sri Lankans themselves need to be bigger cheerleaders and shout about how amazing our food is. One of my goals with the book is to make every Lankan feel proud of our iconic dishes and empower everyone to take them across the world.

Tell us about the research.

This book took a long time to write, about four years. There were months where I would go watch different women cook and watch their techniques. What I learnt while writing the book was that a lot of our food heritage has been recorded as oral history, and that was a large challenge to overcome; I had to understand our colonial history as well as research from Robert Knox and the English interpretations of Mahvamsa to understand when and where our food was impacted. Different communities, like the Arab traders, the Javanese soldiers, and the Europeans (to name a few) have left an indelible mark on our cuisine, introducing their dishes and changing our food forever. It was a fascinating exploration into what makes Sri Lankans who we are today, as a people and a culture.

What is your first Sri Lankan food memory?

Probably my first food memory when it comes to Sri Lankan food was being hand-fed by my mother. She recalls feeding me rice and curry with lots of nutritious greens, and offal-like brain cutlets because it aided brain development. I started seriously cooking Sri Lankan food when I was 18, in my first year of University in London, and I finally realised how integral it was in my diet. That fuelled my passion for learning and cooking Sri Lankan food.

In your quest, have you come across forgotten dishes or unearthed long-lost recipes from the cuisine?

I could speak about this for ages. In fact, I am focusing my second book on the forgotten recipes in Sri Lanka. Many of my family members hail from the western coasts of the island, from a town called Puttalam and the food there is just unreal. I love to go there just to eat — they prepare stingray curry, catfish roe omelettes, and bone marrow curry like nowhere else in the country!

My uncle hails from a southern town where they make beef curry only once a season in Sri Lanka — and it is one of the tastiest things I have ever eaten! He layers a rich, slow-cooked curry with thin slices of daikon and daikon leaves, raw onion, and fluffy white rice; that’s it — no additional dishes can be eaten with it other than a cucumber salad. You cannot get it anywhere else and only the Muslim community in Sri Lanka knows how to make it.

These dishes and the knowledge behind them are likely to get lost because there are very few people remaining who know how to prepare them and that is a scary reality to face.

Though the names differ, the recipes share a certain thread with the coastal regions of South India…

There are so many similarities between Southern Indian food and Sri Lankan food, that we are inextricably linked. So many of our most popular dishes are an evolution of Southern Indian food; appam and hoppers, indiappam, and stringhoppers — these are just a few examples. Sri Lankans have evolved these dishes over time and made them their own — our hopper is a deep-shaped bowl crispy appam whereas its Indian counterpart is shallower and hence the approach to getting the end result is different. I look at the similarities as a positive thing. It represents our long history together and how at the end of the day, we are all connected.

Tell us about your solutions to fight hunger in Sri Lanka.

Sri Lanka is faced with malnutrition on both extremes, wasting and obesity. It all starts with agriculture, and the way we produce needs to systematically change. This is a much bigger issue across the island and will take quite a few years to resolve; our production methods, and why we grow what are challenges the Government of Sri Lanka needs to face and help fix. The market is flooded with the same kind of vegetables every season, and that economically means the farmer earns poorly and that has a ripple effect throughout the country. These men and women are the backbone of our country, and they need to be helped and empowered, and that is one of my key missions.

The other trend that has gone out of fashion in Sri Lanka that I want to revitalise is growing food in your garden and foraging; when I was little, a lot of Sri Lankans grew nutritious greens, flowers, vegetables, and fruits in their gardens or a shared plot of land. Every family and neighbourhood would share their excess crops. This does not tax our soil and provides us with free food, and this is lost art that needs to be turbocharged again.

Furthermore, it seems like fast food is becoming more and more popular and I think that there is no place for it in Sri Lanka. So I want to make eating fresh, home-cooked meals as the coolest way to eat.

As an unofficial ambassador of Sri Lankan cuisine, how do you plan to popularise the recipes, apart from the book?

There are a few projects in the pipeline that I am not at liberty to speak of yet, but the book is the main vehicle. I find spending time with people and starting showcase food events sparks the conversation, so that’s an area I would like to focus on. I want to invest in the Sri Lankan hospitality industry to get them to start building the cuisine across the island and work with women and men in smaller towns and villages to help them bring their food dreams to life. The more that Sri Lankan food wins, the more Sri Lankan people win.

Red Chicken Curry

Ingredients

Marinade for the chicken

500g bone-in chicken thighs (or whole chicken pieces cut up), skin on

2 tsps red chilli powder

1 tsp unroasted curry powder, ½ tsp turmeric powder, ½ tsp salt

20g tamarind or 1½ tsps tamarind paste

360ml thin coconut milk (if tinned, 240ml coconut milk diluted with 120ml water)

2 tbsps coconut oil

1 small red onion, diced

10 curry leaves

½ stem lemongrass, lightly pounded with the back of a knife,

5 cm piece of a pandan leaf, 1 tsp mustard seeds, ½ cinnamon quill, 1 tsp fenugreek seeds

20g garlic and 20g fresh ginger, pound to make a paste, 3 cloves

2 cardamoms, pounded

1 fresh green chilli, diced, 1½ tsps red chilli powder

120ml thick coconut milk

Method

In a bowl, add the chicken, red chilli powder, curry powder, turmeric powder, and salt. Massage the spices into the chicken and marinate for 10 minutes.

Mix the tamarind pieces in the thick coconut milk. Strain and set aside. If using tamarind paste, simply mix into the coconut milk, ensuring all of it is dissolved.

In a deep saucepan with a lid or a Dutch oven, heat the coconut oil over a medium fire. Add the red onion, curry leaves, lemongrass, pandan leaf, mustard seeds, cinnamon quill and fenugreek seeds. Fry for two minutes before adding ginger-garlic paste, cloves, cardamoms and fresh green chilli. Cook for a further 2-3 minutes, before adding the chicken.

Sauté the chicken pieces until it turns golden brown. Pour in the thin coconut milk and cook covered for 20 minutes.

In a small pan, roast the additional 1 ½ teaspoons of red chilli powder for 1 minute or until it turns a little darker. Quickly add the roasted chilli powder into the chicken curry and mix well. This brings the ‘red’ colour to the chicken curry. Cook covered for 5 minutes.

Next, add in the thick coconut milk and mix well. Cook covered for a further 15 minutes on a low heat until a beautiful red gravy has formed and the chicken is cooked through.

Tip: If you want a redder curry, stir in 1 teaspoon of tomato paste into the curry when you mix in the thick coconut milk.

Jackfruit (Polos) Curry

Ingredients

For the curry powder

15 dried red chillies

15 cloves, 6 cardamoms

1 cinnamon quill (5g)

1 levelled tsp pepper

2 levelled tbsps coriander seeds

1 levelled tbsp cumin seeds

For the rest of the curry

½ tsp turmeric powder/paste

2 tsps salt, 500g young jackfruit, cleaned and cut into large equal size pieces

2tbsps coconut oil

50g red onion (½ onion), cut as half moons

4 large garlic cloves (30g), chopped, 8g goraka fruit

2 fresh green chillies, chopped into large pieces

4X7cm piece of pandan leaf

20 curry leaves (5g)

½ tsp fenugreek seeds

½ tsp mustard seeds

500ml thin coconut milk (250ml canned coconut milk, 250ml water mix)

530ml thick coconut milk

Method

Heat a frying pan over a high fire, and roast the curry powder ingredients for 3-4 minutes. Once browned, remove the spices from the heat immediately and set aside. Cool for a few minutes and grind into a fine powder. Set aside.

Combine the turmeric, 1 teaspoon salt and the young jackfruit pieces in a bowl, making sure to coat each piece thoroughly. Set aside.

In a deep saucepan, heat the coconut oil over a medium heat. Add the onion, chopped garlic, goraka, fresh green chillies, pandan leaves, curry leaves, and fry for 3-4 minutes. Stir in the fenugreek and mustard seeds, and fry for another 2 minutes.

Mix in the seasoned young jackfruit, and fry for 4 minutes, making sure to brown it on all sides. Add in 4 heaped tsps curry powder (reserve the spare for later) and fry further for 3 minutes. Stir in the thin coconut milk. Cover and cook for five minutes, then tip in ¾ of the thick coconut milk and stir well.

Allow the curry to come to boil (approximately 5-7 minutes), then turn down the heat to low and cook covered for 20 minutes, stirring occasionally. Stir in 180ml thick coconut milk and cook for 30 minutes on low with the lid covered. Add in 2 heaped teaspoons of the curry powder, 1 teaspoon of salt and mix well. Cook covered for another 10 minutes on low until you have a reduced, thick, dark brown curry.

Pol Sambol

Ingredients

2 tsps ground maldive fish (optional)

1 clove garlic

2 small shallots, roughly chopped

½ tsp salt

2 tbsps red chilli flakes

1 whole coconut, freshly grated (200-250g)

Juice of ½ large lime

Method

Powder the Maldive fish in a spice grinder and set aside.

In a pestle and mortar, pound the garlic, shallots, and salt until you start to form the beginnings of a paste. Add in the chilli flakes, the grated coconut and the pounded Maldive fish. Make sure you mix well and the grated coconut is turning orange.

Once all the ingredients are well combined, pour in the lime juice and pound into the pol sambol and mix again. Serve with stringhoppers or yellow rice.

Book: Jaya Flava

Publisher: HarperCollins Publishers India

Pages: 266

Price: Rs 1,499