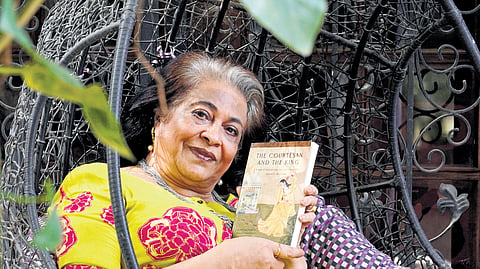

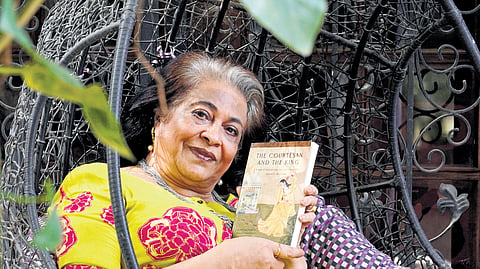

CHENNAI : The regal age of the maharajas was much coveted as it flourished with decadent art and lavish culture. But, with decadence comes power and ego capable of destroying multiple lives, and Sadiqa Peerbhoy’s latest novel The Courtesan and the King deals with one such tale of love, lust, power and destruction. “It is a historical fiction based on the murder of (Abdul Kader) Bawla who was murdered in Mumbai in broad daylight. The media reported it but nobody bothered to find out the small little cause behind this whole murder. A very unknown courtesan called Mumtaz Begum,” says Sadiqa, a seasoned advertising professional.

Twenty-five-year-old Bawla, one of the richest men in colonial Bombay and a corporator in the Bombay Municipal Corporation, was murdered on Malabar Hill on January 12, 1925. The subsequent controversy led to the abdication of Maharaja Tukojirao Holkar III, the ruler of Indore, to avoid an inquiry. Sadiqa’s personal connection to the story through her mother-in-law, who was familiar with the Holkar family and the maharajas, adds depth to her portrayal of Mumtaz.

“My mother-in-law knew the Holkar family which helped me give her (Mumtaz) a voice. I had heard her story many times when she mentioned it but it never occurred to me to write it, and I even knew where she stayed. When she was alive, I could have done such a wonderful job. But recently something triggered and I started doing my research on it,” she says.

After spending a year on research, which included going through newspaper archives, judicial records, and police files, Sadiqa’s book is a mix of historical records and her interpretation of how Mumtaz lived. “I tried to recreate her life, and why and how she became the pawn in this whole struggle of ego,” she says. While there have been investigative books looking at the Bawla Murder Case, this novel is a renewed attempt to look at the story through the eyes of Mumtaz Begum, a third-generation courtesan who became the mistress of Maharaja Tukojirao Holkar III of Indore at the young age of 13.

“She lived there for 11 years and after that somehow she wanted more out of life than just to be somebody’s instrument. So she tried to run away. Although her life was luxurious and everything was paid for, she didn’t want to be loveless,” shares Sadiqa. Begum’s attempt to flee and subsequent life events are central to the narrative. Sadiqa says the Maharaja’s relentless pursuits keep her running from Amritsar to Hyderabad and finally to Bombay. “That was Maharaja’s royal ego, saying, ‘How could she take up with a commoner when I want her?’”

The book also explores the broader context of courtesans in Indian history. “Courtesans were repositories of our culture, music and dance. The entire history of thumri was brought down to our age through courtesans. Begum Akhtar was a courtesan to start with and she became a great singer. They brought this culture down to us. There was no written heritage and at a certain time, youngsters from good families would be sent to them to learn culture and how to be social. Wives were always in pardah and many times were not even literate. But courtesans were literate in their arts. They held a unique position and they were never looked down upon,” explains Sadiqa.

One of the biggest challenges, Sadiqa says, was to piece together all the historical fragments to create a narrative. “Part of the book was about the courtesan culture and heritage and I also had to weave the story in the backdrop of the nascent Independence struggle in the country,” says Sadiqa, who is working on a new project, Partition’s People, which will be a series of short stories based on the lives of families affected by the partition of India.