CHENNAI : When CV Chandrasekhar (CVC) was sent to Rukmini Devi, he was only 10 years old. Chennai was still Madras Presidency then and the slogans of freedom struggle ‘Inquilab’ and ‘Vande mataram’ must also have been ringing around, keeping the spirit of independent India simmering. So CVC’s father, who was part of the British service in New Delhi, intending his child to learn the values and wisdom inherent to the traditional pedagogies comes as no surprise.

Contrary to the popular belief that CVC is a Kalkshetra student, he was in fact a day scholar at the Besant Theosophical school, visiting Kalakshetra only to study the Carnatic tradition. In Kalakshetra’s music programme, he may be the rarest in his generation to have learnt from stalwarts like Boothalur Krishnamurthy Sastrigal, MD Ramanathan, with visiting faculty likes Mysore Vasudevacharya and Karaikudi Sambasiva Iyer.

His daughter, Manjari recounts, “Appa was never a full-time student of Kalakshetra. The story goes that athai (Rukmini Devi) one day spotted him peeping into the classroom of dance; after which she wrote to my grandfather and asked permission for him can be taught dance.”

“My grandfather wrote back to athai saying, “He can learn anything as long as it is at your institution”.”

While under the mentorship of Rukmini Devi, CVC also pursued his undergraduate degree at Vivekananda College. In Kalakshetra’s productions, CVC played character roles as the kattiyakkaran (praise maker) in Kutrala Kuravanji, and as manmatha in Kumarasambhavam. When CVC left the institution in 1954, he not only had a postgraduate diploma in Bharatanatyam; but he also had a Botany degree from Madras University. The quintessential Ramayana productions of Kalakshetra were choreographed from 1955, only after he left.

From Madras, CVC went to Banaras Hindu University (BHU) to do his Master in Botany. Apart from being the housemaster of the hostel in BHU’s residential school, he taught science and music. His elder daughter Chithra comments, “At the time when appa was in Benaras, the society was still conservative. Girls were sent to learn dance, but parents were still hesitant to let them perform. So appa didn’t succeed in making anyone a dancer. However, he definitely seeded the aesthetic sensibilities in them to differentiate good dancing from bad.”

Manjari adds, “What he could not accomplish in Benaras, he did in Baroda. When appa took up as the Head of Department of Performing Arts at MS University Baroda, he had an uninterrupted period when a good batch of students were part of the dance department. That was when he came out with his own productions. Besides adding structure to the academic programme offered by the University, appa’s greatest accomplishment and contribution for Bharatnatyam was how he popularised the art form in North India during the 1960s and 70s in the Hindi heartlands where Kathak ruled supreme.”

Walking shoulder to shoulder with luminaries like Kamalesh Dutt Tripathi, professor emeritus of BHU, and Prem Lata Sharma, linguist, and musicologist, Prof Chandrasekhar absorbed the musicality of the Benaras gharana and the sensibilities of Indian languages. He used these wisely in his own music and dance compositions. Language was never a barrier for CVC; he was able to beautifully appropriate poetries in Gujarati, Kashmiri, and Urdu using the language of gestures. These were the attributes of his art that won him titles and accolades. Prof Chandrasekhar is not only a recipient of Sangeet Natak Akademi but a Padma Bhushan too.

What makes an artiste: The struggles of art or the socio-cultural disparities?

Prof CVC’s demise on June 19 has left a void in the music and dance circle in the city. He is respected, celebrated, and revered in his community because he demonstrated grace and dignity when life threw challenges at him. Praveen, a senior disciple of Prof Chandrasekhar recollects an anecdote that illustrates his moral stature. In his words, “I have done great tours of the US with him. But once, the organisers had promised him something did not keep their word; they had not honoured their financial commitment to him. Irrespective of what the organisers did to him, sir paid us for the tour. I refused to take the payment, but sir insisted that having chosen dance as a career, he wanted to treat them as professionals. That day I learnt how to be ethical as an artiste. He never taught us anything as right or wrong; we always learnt what was right only by observing him closely.”

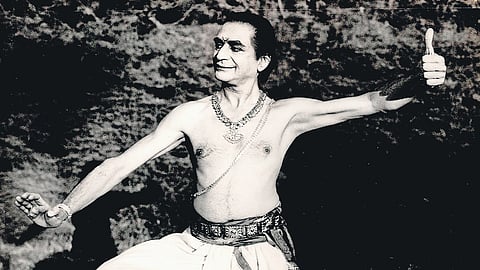

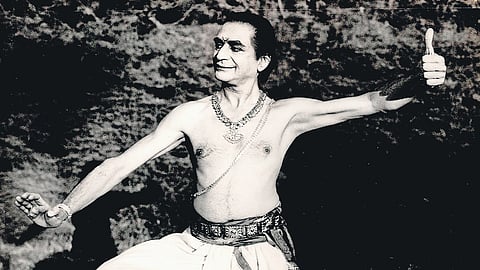

In the history of dance pedagogy and the evolution of Bharatanatyam, academicians of art history and dance will always see CVC’s life and story to be running in parallel. Jayachandran, a respected dance academic and scholar shares, “Chandru sir liberated Bharatanatyam completely from gender bias.”

Explaining how this was important for Bharatanatyam, he says, “The idea behind the dancing body is that it is a transcendental entity: having no physicality of form and therefore par gender. However, traditionally, the patrons of art were males, and in dance, belonging exclusively to the matriarchal community, the female body was getting objectified. So, not just Bharatnatyam, all Devadasi dance forms were trapped in this paradox.”

Jaychandran continues, “If not for Chandru sir this paradox would have remained in Bharatanatyam. He used to perform the nayika-based compositions repeatedly, and with ease. But, to do this, he has had to sustain the wounds created by some critics, who were still looking at Indian dance forms through a keyhole: tearing him up to pieces for his choice of presentation. In truth, what Kelu babu and Maharaj ji did for Odissi and Kathak, Prof CVC did for Bharatanatyam. The shift in vision from a male gaze to a neutral gaze for Bharatanatyam was much needed and happened only due to the tolerance, determination, and conviction of somebody like Prof Chandrasekkar. Otherwise, would we get to see Bharatanatyam as what it is today?”

(The writer is a performing artiste and practicing academic, her expertise extends from Indian art history to other traditions like yoga and Vedic chanting.)