CHENNAI: In May this year, India’s Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change announced at the United Nation’s Forum on Forests that the country’s green cover has been consistently increasing over the last 15 years, and that “Globally, India ranks third in the net gain, in average annual forest area, between 2010 and 2020”.

In the same month, Global Forest Watch released a report that said India lost 2.33 million hectares of forest, equivalent to approximately the size of Meghalaya, between 2002 and 2023. In 2017 alone, the loss was 1,89,000 hectares. The National Green Tribunal has filed a case for the Centre’s response. The Conference of Parties (CoP) 9-Kyoto Protocol lets nations define “forests” for themselves.

According to the India State Forest Report 2021, the legal definition of an Indian forest is: “…all land, more than one hectare in area, with a tree canopy density of more than 10 percent irrespective of ownership and legal status. Such land may not necessarily be a recorded forest area. It also includes orchards, bamboo and palm”. Crown cover needs to be only 10%, and trees on the land need to have a potential minimum height of just two metres.

The Indian definition of forest allows for an inflated calculation of how much forest we still have left. Threats to green spaces are offset optically through initiatives like encouraging “micro forest” growth on megacorporate-owned land. These contribute toward the illusion that India has growing, not rapidly depleting, forest cover.

In February, the Supreme Court of India issued an interim order upholding the landmark Godavarman case of 1996, which fought deforestation. This is in light of amendments in 2023 to the Forest (Conservation) Act, which will lay vast tracts of wilderness vulnerable to destruction (which is one synonym for development). Those with an eye on the environment know that contrary to the optics, India is losing actual forests. Even those without a deep concern ought to be aware of what links the heatwaves and the highways…

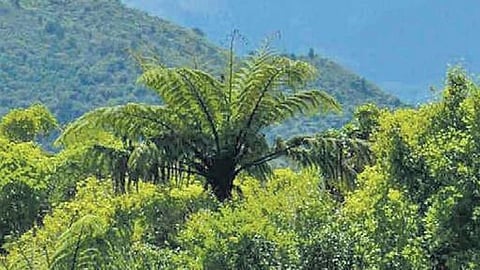

As I write this, I can hear a chainsaw somewhere not too far away from me. I think of how legally, and not just poetically, by the terms defined by the Indian government, I live in a forest.

Ten percent coverage of foliage at least six feet high in a non-congested area is not that unusual. But the forest I am in is changing, and changing, and I keep trying to inure my heart to how it will only continue to. There was a time when I naively thought that all people inherently love and enjoy nature, intrinsically crave sunlight through leaves, canopy-shadow, soft susurrus. Let us define love using the official calculation of “forest”, then: let us say most love trees only 10% as much as I do, and that would still be enough.

If only. I have yet to forget how an officious neighbour, eradicating native shrubbery, defended himself by saying “it was like a forest!” It is, and it should be, but here in my corner of a country where verdure shrinks and shrinks — and everywhere in the world where concrete rises where roots once held strong — so much eco-violence persists.