A fifteen-year-old has been admitted to a burns ward filled with women who survived societal violence. Eyewitnesses, identified as his mother and sister, have given conflicting statements. Each claims to know the truth. Each denies responsibility. Investigators (that’s you, dear reader) are urged to examine all testimonies before deciding who bears the greatest guilt.

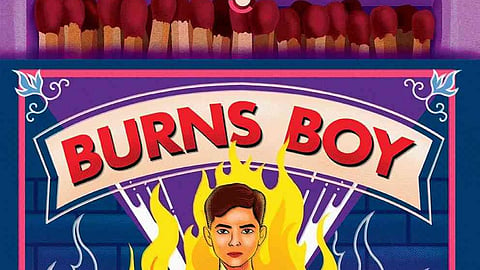

In ‘Burns Boy’ (Westland Books)w, the author Krupa Ge takes us to the 1990s for a family drama steeped in love, guilt, survival, and competing versions of the truth, set in Chennai. The author who has released her second novel walks us through the inception of Burns Boy, the memories associated with it, and more.

Excerpts follow

The book moves between memory, imagination, and reality quite fluidly. Were you conscious of blurring those lines, especially from a child’s perspective?

When I first had the idea, and then the structure, I tried to fit the idea into the structure and make it work. It was a looping process, where each informed the other. So I began with the idea, then asked — how do I make this novel work? Who’s telling the story? What are we going to hear? That became my second preoccupation. And each informed the other.

Can you walk us through how you conceptualised this book?

I first thought of writing another novel when my first novel, ‘What We Know About Her’ came out. I worked on the idea (of a burns boy in a women’s ward) during the second lockdown.

After that, I put it away in cold storage, intending to return to it later. In the meantime, I wrote a memoir with Sanjay Subrahmanyan — ‘On That Note.’ Once that was complete, this rewriting was also going on parallelly. So, it’s been almost five years in the making.

The book opens with a fire accident — an intense and harrowing moment. Did that restrict your writing flow at any point?

Not really. I had spoken to doctors and had some first-hand research. I now know exactly what happens from the moment someone is burned until they’re discharged. So I knew what to expect and didn’t restrict myself. Some people told me they felt pin pricks all over their bodies while reading certain lines. That was a very intense thing for me to hear. I suppose that meant I got something right there.

The burns ward in the novel is full of women who are survivors of domestic violence, acid attacks and other gender-based violence. Was placing a boy in that space always part of your plan?

Yes. It was a question of what it is like for a boy to be in such a space. These accidents do happen. What is a boy who has gone through something like this going to experience in that world? The book is set in the ’90s, when that sort of reality was even more common — gas cylinders exploding randomly. I had attended a burns conference during my MA in sociology, sometime between 2006 and 2008. It focused on how society reacts to burns victims. Doctors spoke about what they see among the mostly female patients. That conference had a lasting impact on me, and while writing the book, it was always at the back of my mind (that responsibility).

Each family member in the novel carries their own version of guilt. Did you ever feel more drawn to one character’s perspective?

For me, all of them are actually me. So, preferring one over the other wouldn’t be possible.

I did enjoy writing the daughter’s voice though, that’s not how I usually talk. But I wanted to capture people who do speak like that. I wanted to evoke this playful, Indian, casual way of speaking English. It doesn’t come naturally to me but that voice ended up being, at first, the most difficult and later, the most fun to write.

The book deals with themes of love and damage within families. Was this something you set out to explore?

Absolutely. I wanted to tell a story that was as close-up as possible. My previous novel (‘What We Know About Her’) was sweeping in that sense — larger, with more characters and themes. But here, I wanted to get inside someone’s skin and ask: how much do we really need to know about a person to care about them? There aren’t elaborate backstories in this novel. There are stories, yes, but not sweeping ones. You don’t know much about the characters apart from their thoughts and what they tell you. That’s what I wanted — to examine family dynamics from up close and see what emerges.

Did you draw on childhood memories for the book?

Oh, definitely. All my fiction draws freely from life. Nothing in particular, but I did recreate the feeling of a ’90s childhood, drawn from my own experience as a school-going kid in Chennai.

I wanted to create a flavour profile rather than a sightseeing tour of the city. Things like going to a friend’s house without informing your parents when there were no mobile phones, or sneaking off to a bakery after class. Sweet coffee sessions among government employees. The fact that many Tamil writers worked government jobs and wrote under pseudonyms. That sort of texture. I wanted the challenge to be, not just saying “I’m on this bus from here to there”, but to immerse the reader in that Chennai. That comes from having lived in the city all my life.

What kind of reading feeds your writing the most?

I read widely and variedly. For this book, reading Jayakanthan during college was a major influence — especially as the mother, a writer character, is influenced by him too.

This past year, I’ve read a lot of Tamil writers for a project, especially novellas. I think that influenced the short length of this novel. I’ve been reading intense but compact books. I enjoy Domenico Starnone, Elena Ferrante, Vivek Shanbhag, Jerry Pinto, Mieko Kawakami, and Yoko Ogawa.

You were longlisted for the JCB Prize. Now that it’s unofficially said to be discontinued, how do you view this development?

What’s missing now is a strong tastemaker who tells readers whom to read. Even that basic thing is vanishing in India. Writers like Perumal Murugan and S Hareesh being recognised by JCB mattered as they write in Indian languages and about urgent subjects. I hope something will fill that vacuum. I hope someone steps in or the prize reinvents itself and returns.

How do you see the current reading culture in India, with so many distractions and new mediums?

This ties into what I said about the JCB. We don’t have a definitive go-to for book recommendations. If someone wants to know who the best writers are — where do they go?

That said, reading culture is evolving. Some amazing independent bookshops are coming up — Silverfish is even giving away awards and curating books with staff picks. Champaca in Bengaluru, Higginbothams in Bengaluru and Chennai, Crosswords, Odyssey in Chennai, smaller shops like The Bookshop Inc and Walking Book Fair — all of them are all doing something vital. They foster reading. You sit in a bookshop, you read, you immerse yourself. I’m not convinced social media can do the same. Unless there’s a strong space for book conversations — which is hard, because it’s a visual medium. Maybe podcasts are helping.

Step Inside The World Of Burns Boy

Burns Boy Installation + Scavenger Hunt & Story-Building Activity

In collaboration with @kannadi.cupboard on Instagram

Date: August 23 & 24, 5:00 pm – 7:00 pm