Even before the crack of dawn, Chennaiites wake up to the musical notes of birds, the winter wind so chilly that it demands a woolen armour to brave the streets that stir to life as the day progresses. Men, women, and children gather to sweep their respective thresholds and sprinkle water as a ritual and then create pattern of curves, grids, dots, lines, and loops.

This art form — kolam — holds a special significance during the Tamil month of Margazhi, which falls in December. Traditionally, kolam is believed to symbolise prosperity, good luck, and welcome goddess Lakshmi into homes. It is also said that kolam wards off evil energies and spirits.

Kolams are practised differently in different parts of the country: Pookalam in Kerala, Muggulu in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, Alpana in West Bengal, Rangoli in Karnataka, and Sathiya in Gujarat.

Mention of this practice in Tamil lit can be traced back to Sangam literature, dating from the third century BCE to third century CE. “In this literature, the description of drawing kolams exactly matches the visuals seen on the streets of Chennai today. This shows how age-old the practice of kolam is,” shares historian Meenakshi Devaraj.

The 15th verse of the second chapter, 518th verse overall, in revered poet and saint Andal’s Nachiyar Thirumozhi reads, “Vellai nunmanal kondu sittril visiththirapada”, which roughly translates to: using fine white sand, we carefully draw beautiful kolams on the streets. There are also literary sources that show men indulging in this exercise. A 12th century poem mentions a ghost, presumably male, making “decorative patterns” from pearl dust.

According to Meenakshi, “The practice of drawing kolam has evolved over centuries.” This shows the dynamic nature of this custom. The other characteristics include constantly changing in terms of its designs and colours. Adding to the list, Meenakshi notes, “It is therapeutic. It brought some healing in me.”

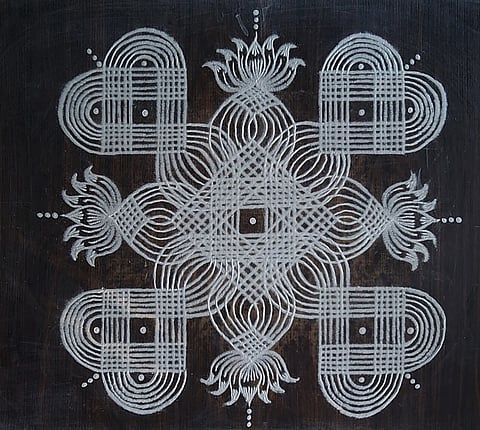

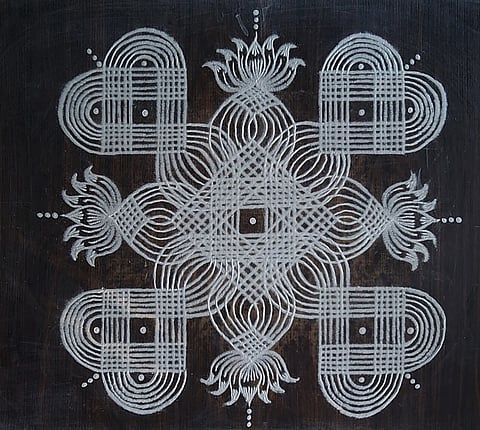

Sacred patterns on streets

This ever-evolving art form finds its expression during Margazhi as this Tamil month brings with it “positivity and happiness”. Vardhani KL, a software analyst (@kolamveri on Instagram), shares, “I always look forward to Margazhi. It is one of my favourite months because it is winter. When you wake up, you see how beautiful the climate is. It is also the season of bhajans and keerthans. And when you do the kolam, you hear them.”

She describes kolams as a habit of “decorating our homes. It is an extension to the decoration we do inside.” Vardhani urges that everyone should come forward and take up this habit and it shouldn’t be restricted to a particular religion or region.

Meenakshi echoes the same thoughts. “Schools should recognise this practice and encourage kids to take it up. Kolam shouldn’t be shrunk to a particular religion, and to women,” she says.

“Usually there is a gender restriction that it should be done only by ladies in the family but the case is not like that for us because it’s just an art form. The main point here is that tradition should not be lost,” says Jayashankar Sreenivasan (@mrsandmrkolam on Instagram).

Jayashankar learnt this skill from his chithi (aunt) and his mother. He shares, “Every morning, they put kolam on the threshold. Sitting there and watching them raised an interest in me. I thought this form should not be restricted only to the female community. Why should girls have all the fun?” His family was supportive and encouraged him in building this talent and excelling. “With respect to my wife, she has the leverage of doing it. Nobody is going to stop her,” he remarked. His wife keeps the dots and he continues the kolam, he says, adding, “We discuss what kind of designs to draw the next day. It brought a uniqueness in our collaborative creativity.”

Visual grammar

In any pattern, keeping a symmetric dot is pivotal. “If the dots are haywire, your design goes haywire,” points out Jayashankar. The dots are then followed by designs and patterns. “I bring geometry into my designs. Celtic designs are popular in foreign countries especially in Europe and the UK. It’s looked upon as a symbol of oneness. Our temple carvings have celtic designs. We brought such kinds into our kolam designs,” he shares.

Once the intricate designs are outlined, it is then filled with colours, not every but a select few, each carrying a symbolic meaning. The popular kaavi (red) colour represents auspiciousness. When added with white, it brings in the value of Shiva and Shakti. “The white is Shiva and the red is the Shakti,” explains Jayashankar. Additionally, manjal (yellow) adds a devotional aspect to the kolam. To please the eyes, green and blue colours are included. “Green is pasumai. Blue is water, neer. It is also associated with agayam,” he says. Nowadays using grey and black has become a common practice.

The 2025 Margazhi

This Margazhi season, while Meenakshi will follow her tradition of showing the verses of Thiruppavai in her kolams, Varadhini is excited about her chikku kolams, Jayashankar and his wife are are working on a series of new designs, something on aspects of Andal Pasurams. “We want to depict it in the chikku kolam and padi kolam. Ensuring we keep it traditional rather than trying something with the latest trend,” he concludes.