What does it mean to be raised in a society where your position has already been determined, only because of an unfortunate event? At the age of 14, Arali is pushed to live in a world constructed by societal norms. She finds herself stuck between tradition and change, childhood and adulthood.

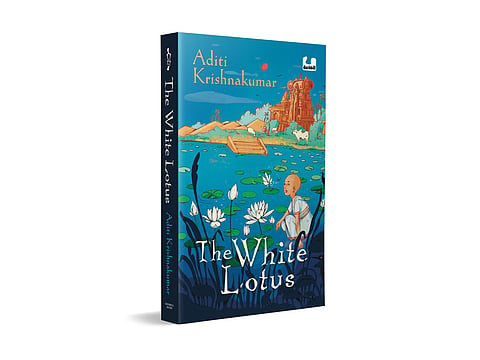

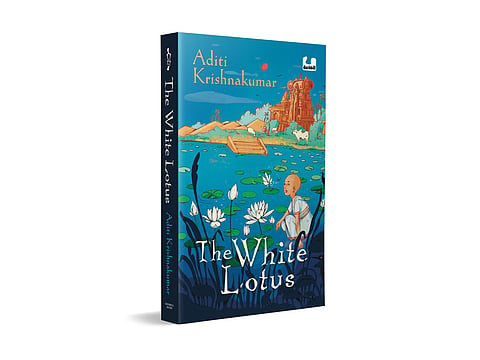

Arali, the protagonist of The White Lotus, published by Duckbill (An imprint of Penguin Random House India), tries to defy the norms and is set on a quest for agency, identity, and to clear her dead husband’s name. Sundaram, Arali’s husband, is nothing but honest, gentle, and dutiful — the very qualities that guide Arali to build a life on her own, day after day. “I had a general idea that I wanted to do a period setting. It was going to be about a young woman and her quest for agency and identity,” says Aditi Krishnakumar, the author of the book that is set in the 1900s.

This historical fiction with a murder mystery twist echoes across time and addresses the issues of choices and womanhood that are still incredibly pertinent today.

Excerpts follow:

What drew you to set the story in Tamil Nadu and explore a historical timeline through your characters?

The story is set in Tamil Nadu, partly because I have had the chance to have a lot of experience at my grandparents’ villages, and I have been there often. With this particular book and this particular character, I was coming from a place where people still have the same or similar ideas, hopes, fears, and everyday worries. I think the book was coming from a place of exploring the experiences that my great-grandmother’s or great-great-grandmother’s generation would have had while growing u,p and what that might have been like.

Did you always want strong female characters?

To some degree, it was intentional. Because I have heard a lot of stories, and the thing that always came through for me about women, especially, is that they were strong. They had to be strong characters because they were, in some way, living in a harder world where there was infant mortality, and they did not have modern medicine or facilities. I always found that very impressive about them.

Ultimately, I feel that it is important, especially when you are writing for young people, for children. Not just to start with a character who is strong from the beginning, but to show that growth is happening. It shows how your circumstances and events that happened to you, and how you react to them, make you a strong person.

How did you write Arali, a 14-year-old caught between childhood and adulthood in a different era, yet dealing with feelings that are relatable today?

It probably happens with all of us when we are facing a major life change, or maybe when we are growing, we tend to do something new, and then we feel a bit scared, and then we try again. Sometimes it is about taking a step forward and back. Fourteen-year-olds then and now, in some ways, would have been very similar because that is an age when you are trying to find out who you are.

Now, of course, children do not get married that young. But at that time the story is set, if the husband had not died, there would have been another factor, where she would have been a mistress of her own small family. To some degree, that would have propelled her to grow up.

At the same time, if her husband had been alive, she would have been his wife and considered a mature woman or a grown-up woman by society. So, there is this interplay going on in her mind as well as in the thoughts of people around her.

Unfortunately for her, Arali’s husband had always had to exit the picture fairly early in order to allow that side of the story to happen, in order for children to take an interest in Arali and all that followed.

Given that Arali was growing up in the 1900s, where most decisions are made for you, do you think she would have comprehended what it means to be a ‘widow’ and accept her husband’s death?

One thing that is going in Arali’s favour is that she is going to get an education and presumably going to have financial independence. Child widows, aside from the grief of losing their husbands, how well did they know their husbands to actually love them? What was the level of personal grief for them? It is hard to say. But they were definitely losing something very big in life. They have, perhaps, seventy, eighty years ahead of them. They are going to be dependent on various people who may not treat them very well again. So, that part of her life, the daily unhappinesses and people making remarks about her...hopefully, Arali will not have to face because she is going to have a career. But at some level, I think she will understand.

I do not want to say she will never get married and never have children, but everyone always has to make choices, and perhaps she will feel a little melancholic for what could have been. But I do think she will get over it because she is young and people are resilient..

Fantasy gives room for metaphor, but politics necessitates precision. How did you bridge the gap between them?

Probably everywhere in the world, and India, life is like that. At some level, all of us are engaging with the whole social structure or the gender structure, and the class structure. It is not something you can opt out of. Or if you can opt out of it, it is purely because you are in a position of privilege.

At the same time, when you are writing a story, you do not want that to take away from the plot. It is simply a question of striking a balance between the elements of moving the story forward and what is going on. The key to that is looking at how the existence of various social and political structures would have affected people in their everyday lives and being aware of that. You do not necessarily push it, but you are aware that it exists.

Even if you try to make this perfect society where everything is equal, at some point, power structures will emerge. What may change is the equation between who has the power and who does not. Even now, there are, of course, power inequalities based on gender, economic background, and class. But if these were not there, let us say four hundred years into the future, we have eliminated all of this, then there will simply be some other basis on which there is a power inequality. The functioning of a society is based on how a lot of people try to write these inequalities and other people try to achieve equality, which then, at some point, becomes inequality again. That is just a cycle that keeps happening.

Did you have an ending in mind, or did it evolve when you were writing the story?

Very often, the ending evolves while writing the story. One thing I was not sure of at the beginning, which ultimately was what happened in the end, was whether I actually wanted Arali to leave the city. That seemed to make sense, because for her, as a widow, she would probably have had to travel to get away from the past and get opportunities. Perhaps she would have come back later when most of it was forgotten, and as she became older.

Do you think the quest for identity and the struggle against inequality are timeless human experiences, no matter the era?

People do go on a quest for identity. Especially now, because the school system encourages children and adults to find out who they are. In the timeline the book is set in, if your father is a farmer, you’re a farmer. If you are a woman, then you are a farmer’s wife. So, there are definitely more opportunities for people to find themselves & discover who they are, now.

The book weaves themes like identity, selfhood, and social roles. Can you list a few themes that are important for the readers?

One of the major themes, for me, is coming-of-age and discovering yourself, discovering your agency. Probably a lot of novels that are written for and about children of that age will have the same message because that is also the teenage years, and one may discover oneself. You could discover agency at any age. But this is perhaps when it starts happening, when you really start thinking about who you are, and who you want to be.

One thing about historical fiction is that, I think, it is a mistake to characterise all people in the past as unenlightened or awful because they did many things that we do not approve of now. I am sure we do many things that people two hundred years later will not approve of. Most people then were good people who were just doing their best to live their lives in a society that existed then.

Just like now, not everyone is a moral philosopher; everyone was not a moral philosopher then. Some people bring change by marching on the streets. Some people are the ones who bring change quietly into their lives simply by doing things differently. And both are valid.