CHENNAI: Inspiration came to Himmat Shah in Garhi at a time when the Lalit Kala studios in a fringe South Delhi colony were the haunt of artists on the cusp of fame. Here, you could hope to find Krishen Khanna working on the murals for ITC Maurya, cadge a cup of tea off Manjit Bawa, watch Paramjit Singh struggle to capture the haunting light in his landscapes, drop in on Mrinalini Mukherjee for a chat, head for J. Swaminathan’s addas that were known for their fiery rhetoric, or join a queue of printmakers waiting their turn at the printmaking unit.

When Swaminathan moved to Bhopal to set up Roopankar Museum in the Bharat Bhavan complex, Himmat Shah inherited his studio. Ved Nayar was next door and believed that Shah’s elongated terracotta Heads were inspired by his practice at the time.

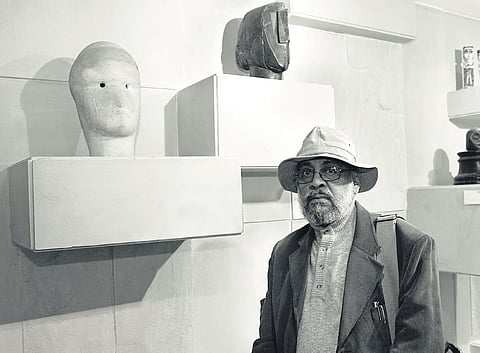

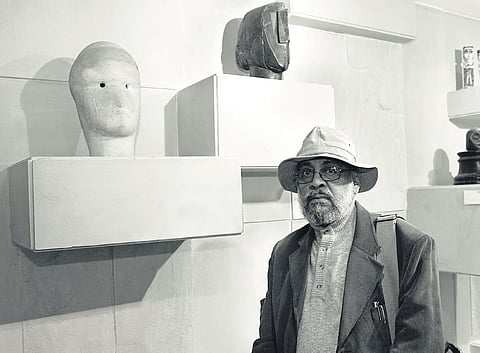

Himmatbhai never cared too much for the proprieties of the art world. His dour expression was part of his demeanour to warn the world that he suffered no fools. His early inspiration came from the excavation sites of Lothal in Gujarat, where he was born, and the primordial mysteries of what had gone before remained with him till the end of his time…which came following a period of ill-health, on Sunday.

But Shah was never oblivious of linear time. In his studio, you would find clay that he had cured decades ago, using a little bit of it every time he kneaded a new stock, not unlike a sourdough starter. For the sculptor, though, it was in this continuity that he hoped to connect with the past.

Having trained in Baroda at the fledgling Faculty of Fine Arts, Shah set his eyes on clay as his chosen medium and sculpture as his genre, challenging the template of India’s decorative aesthetic. In the 1960s, as a member of Group 1890 into which he was inducted by Swaminathan, he burnt paper to turn into collages. It was understandable that critical interest did not generate into buyer interest.

His drawings from the same period are examples of detailed cross hatching. At any rate, Octavio Paz, who had seen his work as Mexico’s ambassador in New Delhi, recommended him for a scholarship to train in printmaking at Atelier 17 in Paris.

Shah always recalled his Garhi years as his most experimental, a time when he drew, painted, worked with found objects and began to be noticed for his terracotta sculptures that would establish his reputation as one of India’s leading sculptors. But Himmatbhai did not care much for the cultural ennui that he experienced in New Delhi and chose to escape to Jaipur, where his studio soon became a meeting point for local potters and painters.

At Garhi, Himmatbhai had escaped my attention as a rookie journalist but I was introduced to him in Jaipur by Kripal Singh Shekhawat, the two having struck up a close friendship even though their practices were vastly different. Kripal Singhji was a fount of information on local cultures and practices for my research on the state’s history.

Shah’s studio, where I met him, was like a kabari shop with mounds of clay resting under wetted jute, strewn with unused tyres, nails, empty bottles, boxes and jars that would serve as an improbable muse for his sculptures. He extolled objects of daily life in the same way that Prabhakar Barwe did in his paintings, and though he was admired, local interest in terracotta tyres and bottles was understandably low.

Nor was Himmatbhai easy to talk to, sullen in his answers but excited, always, about his work. He had the patience to work with and fire clay but was hard put to extend the same courtesy to his fellow humans.

He seemed always in a hurry, frenetic, and cared little for social graces. He enjoyed the spotlight on his work but never on himself, his absence from exhibition openings or panel discussions taken, over time, for granted. It frustrated gallerists but freed up curators, critics and collectors to look at his work purely on its merit.

His physical absence may therefore go unremarked amidst his legions of admirers, but the touch of his hands on his works will retain a bit of Himmatbhai in each of his sculptures, serving as the bridge across time that he worked so hard to create throughout his life.

(Kishore Singh is an art writer, curator and former columnist who has authored a number of books on a range of subjects including travel, history and art.)