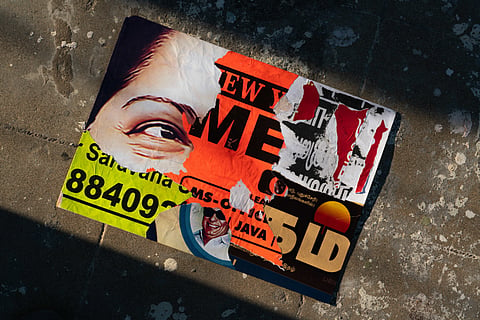

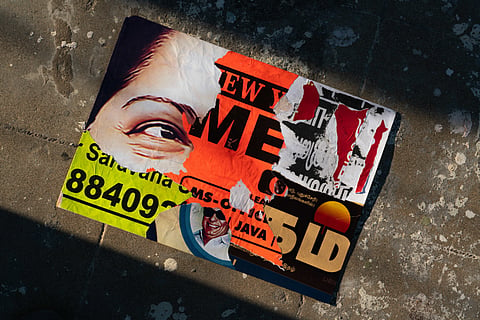

Walk through Chennai, and its walls speak in fragments. Torn Tamil letters overlap one another. Fluorescent paper curls at the edges, sun-bleached and rain-worn. Headlines fracture mid-word as newer posters are pasted over older ones. A woman’s eye peers out from behind a strip of red paper.

For visual artist and graphic designer Girivarshan Balasubramanian, this everyday typography is a language in itself, shaped by use, and neglect.

Everyday tactile materials, he says, draw his eye, listing receipts, bus tickets, parking slips, newspapers, and wall posters. What interests him is not polish but presence. The appeal, he explains, lies in imbalance. Perfect design rarely holds his attention. “When something is out of place a bit, you start to notice,” he says. Torn edges, fading ink and overlapping posters reveal something unmistakably human.

This fascination with wear and repetition forms the backbone of Girivarshan’s collage practice, particularly his work rooted in Chennai’s streets. Using fragments of posters collected from walls, tea stalls, and public spaces, he reconstructs the city’s visual language into layered compositions that mirror how the city functions.

The city’s typography

Ask Girivarshan what Chennai’s typographic culture says about how the city communicates, and he speaks of sameness. “There’s an unsaid visual language which exists right from commonly used materials and design styles,” he says. Newsprint advertisements, tea stall posters, and hand-painted notices often share the same paper, the same scale and the same urgency. This shared grammar allows the city to speak quickly. Whether it is a political campaign, a cinema announcement, or a handwritten signboard, the intention remains consistent. “They all want to communicate. They all want bypassers to look instantly and be like, ‘hey, that’s amazing’, or just read whatever they’re trying to communicate and then take that message.”

What emerges is a collective visual habit rather than an imposed rulebook. “It forms an unsaid rule, but it’s so beautiful, and everyone keeps doing the same thing over and over again,” he says.

Craft and convenience

This visual culture, however, is changing. Girivarshan is candid about the loss that comes with digital dominance. “It’s a bit disheartening to see the use of handcraft skills slowly disappearing,” he says, pointing to hand painters whose demand has declined with the rise of flex prints and digital banners.

His interactions with hand painters during his master’s research left a lasting impression. Speaking to painters in Chennai, he was struck by their skill. “They’re extremely skilled with very limited access to technology, and they have an insane amount of craft,” he says. One painter told him that when he was learning, he could not afford paint or brushes and practised by using water on the floor to understand how letters moved.

While Girivarshan acknowledges that such shifts are inevitable, he is critical of what replaces them. “Lot of the visual elements we interact with nowadays have no soul,” he says, describing banners and flex signs that simply scream their message. In contrast, older signage carried intention.

But this artist is drawn to what happens after intention fades. That is when he feels compelled to collect or document them, a process that eventually led to his Streets of Chennai (collecting the typography of the city) series.

These observations eventually shaped ‘Stick No Bills’, Girivarshan’s master’s thesis project at RMIT University. Conceived as a publication rather than an exhibition, the project acts as a guide for emerging Indian street artists. “My intention behind doing that research was not to tell people to leave their jobs,” he says. Instead, it was about showing that “there is this art scene which is coming up in India” and that there is space for artists.

The choice of print was personal. “A publication is very simple because I just love designing books,” he says. Designed to resemble a photocopied guide, the book brings together interviews, case studies, and visual references drawn from his research and fieldwork.

Though the project is not publicly available, its ideas continue to inform his practice. Today, Girivarshan works as a designer in Melbourne, carrying Chennai’s streets with him through collage, typography, and an enduring respect for materials shaped by time.

To follow his work, find him on Instagram @giri.varshan.