When misogyny is the joke: How gendered humor is flooding Instagram reels

Laughter, at its most primal, can be read as a feral animal instinct rather than a refined social response. We laugh when we see someone fall, not always out of cruelty, but out of a reflex, since at that moment, our body and mind reacts before empathy arrives. This kind of laughter is involuntary, erupting as a quick emotional discharge that precedes moral reasoning.

That raw instinct is what humour has long harnessed as a catalyst, especially in cinema. Tamil films, for decades, relied on side-kick comedians who amplified this reflex through slapstick and mockery. Today, many of these comedians are losing relevance, as audiences increasingly call out humour rooted in distaste; often made in demeaning, classist, or gendered fashion. Yet some of these jokes still work, not because they are defensible, but because nostalgia cushions them, and in some cases, slapstick’s physicality bypasses intellect, triggering laughter.

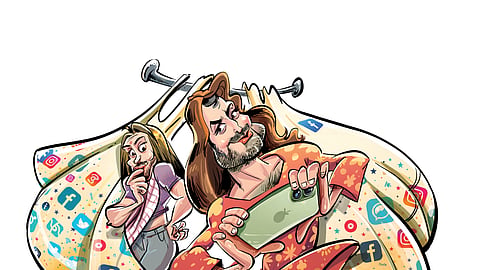

While cinema is gradually steering away from this brand of humour, something more pervasive and dangerous has taken its place: social media. Short-form videos now flood our screens with influencers performing gendered comedy, leaning on exaggerated props, clothing, makeup, and stereotypes to provoke quick laughs.

Much of this influencer-driven content relies on visual cues to signal “womanhood”. A wig or even a shirt draped like hair, lipstick, a bindi, a dupatta thrown across to mimic a sari, or a nighty worn over everyday clothes. These performances flatten women into caricatures and delegitimise their relationships and emotional worlds. In many such videos, mothers are reduced to nagging or melodramatic figures, mother-in-law–daughter-in-law dynamics become petty battlegrounds, and young women are portrayed either as frivolous man-rejectors or infantilised as ‘daddy’s little princesses.’ Across these skits, women are not individuals but tropes — ‘brainless cute girls’, ‘compulsive shoppers’, ‘gossipers’, or ‘women who undermine other women’.

Consumed in isolation these may seem harmless, but collectively they normalise offense at scale. Swapna Gopinath, professor and academician, explains the harm. “Earlier, people would go to theatres to watch a film, encountering its humour in contained doses. But with the arrival of television and multiple channels, the same comic scenes began to play again. What was once occasional entertainment, is turned into consistent exposure. Today, this repetition has multiplied across platforms and formats,” she says, adding how the same jokes resurface as clips, memes, reels, and remixes, embedding themselves through rote learning “reinforced by vivid visual imagery”. Over time, repetition doesn’t just entertain, it conditions.

Maya S Krishnan, actor and comedian, seconds this. “Repetition normalises ideas. When millions consume the same jokes again and again, it subtly reinforces the belief that these stereotypes are “natural.” That’s how inequality survives. Through laughter. It may seem like ‘just jokes’, but jokes shape culture more than we admit.”

Repetition marketed as relatability

Many creators justify such gendered content by claiming it is drawn from “observing the women around them”, often reinforcing the claim by running polls that ask viewers whether the skits are “relatable.” Yet, who is actually clicking on ‘relatable’ — women, men, queer, or gender non-conforming individuals — remains unknown, since platforms like Instagram withhold such data from the viewers.

Archanaa Sekar, Chennai-based feminist activist, writer, and researcher, says she is hardly convinced by such observations and relatability. “After watching their content, I feel that they either don’t research at all or are really disinterested in understanding how women’s worlds operate,” she comments.

Swapna, however, argues that both “observation” and “relatability” are shaped by prior consumption. She explains that when creators claim they are merely reflecting society, the assertion itself is flawed as observation is never neutral, and in matters of gender it is inevitably coloured by biases. What is presented as “observation”, she says, is often what they have consumed on screens or exposed to in patriarchal spaces like Indian homes where, stereotypes are endlessly recycled and masqueraded as the truth.

As someone who writes comedy, Maya believes that humour should question power and not “babysit it”. “When humour relies on reducing women to tropes, it becomes lazy, predictable, and honestly boring.”

Double exploitation

Much of such misogynistic viral content created by men thrives on portraying women as infantilised, expected to look and behave in an immature fashion, remain dependent, and unserious. All of these are characteristic expectations that have long been enforced by patriarchy itself. Yet the same society that demands this performance is quick to ridicule real women for exhibiting those very traits. This results in a double exploitation, Swapna observes, as women are first shaped and reduced into childish tropes [such as daddy’s little princess] for control, content creators are then given credit for the same portrayal and somehow still, women are shamed for conforming to the same image imposed on them. “It is a kind of systemic violence,” she asserts.

Do you follow a male content creator who dresses up as women and mocks women's behaviour for comedic effect? Here is why you should re-think double tapping on their content.

Many of these short skits are also set in women-only spaces, like women’s hostels, and in them, the female characters are made out as jealous back-bitters who don’t wish each other well. Archanaa says, “I think men have always been very curious about what goes on inside women-only spaces and that becomes apparent in such reels. They want to know what goes on in there and they have their own fantasies, but no one seems to know.” She adds that men, therefore, project what they think happens and that their projection of women fighting each other, is far from the truth. “Historically and practically speaking, it is patriarchy that keeps us competitive and wary of each other as women. But those of us who have broken away from it hold such spaces sacred and we want to keep those women-only spaces private. Not make content out of it,” she notes, adding, “Even if we did, it would be more real than how these men make it seem.”

The visual cues

These creators also rely on hyper-feminine props such as long hair, exaggerated nails improvised from stick-ons or petals, heavy makeup, and smeared lipstick, all of which Harish Subramanian, a queer resident of Chennai, refers to as visual “shortcuts” to “femininity”. In parodying women, these elements are stripped of agency and turned into cues for ridicule, teaching audiences to laugh at its visibility rather than respecting its legitimacy. Archanaa even comments, “Makeup by these men is not being used as a tool for empowerment, creativity, or statement. They are reducing it to what we have been struggling to fight, which is that wearing make up is associated with women only, it means wanting more attention, and as a woman trying really hard.”

Harish clarifies that the issue with these creators is not cross-gender performance itself but the intention and the gaze through which these performances are framed.

Such acts create a certain power imbalance, too. When men dress up as women for comedy, behind closed doors and in front of a camera, they do so without risking the harassment that real women or queer and gender-nonconforming people face in public and online spaces. That, Archanaa says, is a privilege these men have.

Harish expands, “For cis-het men in content creation, femininity is a costume, a caricature they can get in and out of just for engagement — likes, and views. But that’s not the case for women, trans persons, or queer people because it isn’t that easy. Trans and queer people take years to develop the ability and courage to wear the clothes we feel comfortable in and clothes that don’t give us gender dysphoria.” He further points out that the difference underscores the seriousness of the harm that content creators’ performance on social media poses as it teaches people to read, judge, and police identities.

At this point, the question also arises whether the intent of such creators deserves any weight at all. To this, Maya responds with clarity. “Firstly, intent is often used as a convenient shield, but intent cannot cancel impact. Secondly, observation without context or self-reflection is not neutral and such observations usually sides with the dominant narrative. When creators refuse responsibility but still benefit from virality, that’s not innocence,” she says, asserting, “Comedy does not exist in a vacuum.”

Harish seconds this and explains that a creator may or may not intend harm but if they are circulating a stereotype repeatedly it affirms a perception. “Like how colourism works or how what is good and bad hold ground in society. It doesn’t necessarily have to be a bad intention or a malice. It only requires you to constantly put it out again mechanically without any reflection on the action nor its consequences.”

The issue also lies with platform algorithms. Maya points out that gendered humour, especially misogynistic humour, is rewarded by algorithms as they trigger strong reactions such as laughter, anger, and even responses like shares or debates. This incentivises the creator economics as opposed to nuanced and thoughtful humour. Swapna talks about this by referring to the rise of manosphere’s relevance among the youth, pointing out how easily algorithms can be exploited, especially within digital spaces that are already gendered.

More troubling is consumers’ passive complicity. We watch, like, scroll, and move on without reflection, training the algorithm to serve us more of the same. The onus, therefore, shifts onto the consumers of such content, Archanaa notes. “If you think about it, we are mindlessly consuming such content. If a video makes us smile even for a micro-second, we are double tapping, offering the validation the creators need and that is incentivising them to create more such content,” she adds.

Swapna also believes that engaging rightly with such misogynistic content is very important. “Most people will just shut it out as “cringe” and they don’t respond. But people need to call out such creators or agree with someone calling them out in the comments, and not give them the likes that are validating them. Sometimes one may get hate for it but it is the only way to deal with it.”

Maya expresses that revolution here will only begin with disapproving such content as relevant, relatable or enjoyable. “That way, creators are posed with the question of, ‘Who is this joke serving?’ So, I believe that change doesn’t start with cancel culture. It starts with conscious consumption,” she concludes.