The question is searching but the answer rests within it. Each one of us has to peek inside ourselves to speculate how the Indian letterform, specifically Devanagri script, never made it to contemporary times. After all, each one of us is guilty of letting our written legacy slip to global aspirations. Artist Rajeev Prakash Khare, however, has taken upon himself to investigate this great loss that he feels India is still oblivious to. Along with artist Shubhra Prakash, he studies how much is lost and what remains from the time when history was written in stone and metal, to now, when the letterform has found itself dangling on various technical mediums in an exhibit titled Fontwala: Stone to mobile, what remains?

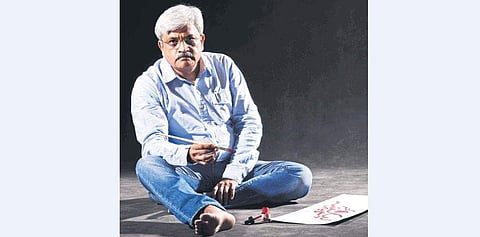

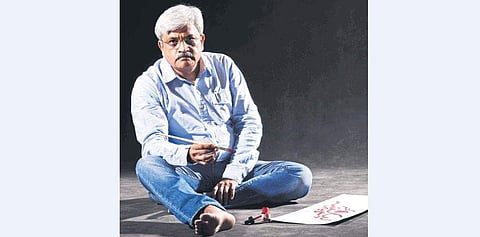

Presented by Kaleidoscope Digital Art (KDA), there are seven videos in the exhibition. They trace the development of Devnagri from Brahimi, the mother of all scripts. “How it evolved from stone pillars to digital screens. We see the rudimentary linkages of akshars and the beauty of the script with its maatras and accents,” says Delhi based 57-year-old Khare, who was mentored as a calligrapher and typographer under by well-known calligrapher and father of today’s digital Indian language typography, the late Prof RK Joshi and Gopal Bhai Modi, Founder of Gujarat Type Foundry, Mumbai.

Loss of language results in the loss of culture, he believes. This makes language preservation a national priority. “From engraving on stones to tampatra to paper to the screen of your computer, lettering has changed dynamically,”

If you wanted to search for a book you read in the first grade, would you be able to find it? No, because the syllabus has changed and the old one isn’t archived. Will your CD drive work faultlessly after a decade of having been kept aside? No, it would have developed a snag.

The old becomes obsolete but not in the case of engravings, he says. “The Ashoka Pillar, for examples, can never be gotten rid of its engravings despite floods or torrential rains,” he says, believing that language is going through fragile times.

He is also deeply discouraged that local scripts have been substituted by the politically dominant script pointing to the dilution of the indigenous writing approach.

The need of the hour is to include typography in the syllabus of design schools. And it should not be English typography or Roman, but local language ones. Otherwise, how will our students understand and appreciate their script, questions Khare.

He fondly remembers the time when his father would make him write sulekha or creative writing in Hindi with his bamboo kalam (pen). “I still write with a similar pen. For me, it’s about continuity. And that’s exactly what we need from this generation to protect our written legacy,” he says.

On: August 17, At: Digital Art Gallery, Triveni Kala Sangham