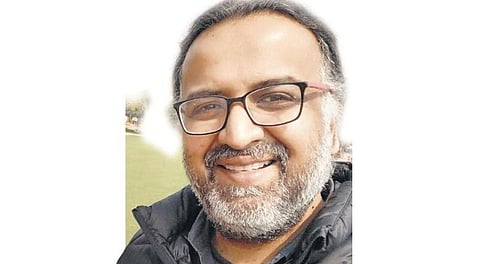

Amitabha Bagchi recently picked up the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature 2019 for his novel, Half The Night Is Gone, described as ‘a post-colonial saga that unfolds over three generations, exploring human relationships and the intertwining of fates and cultures, in a thoroughly Indian context’. We spoke with Bagchi about his book, and the far-reaching changes apparent in Indian society lately.

Excerpts:

Do you imagine there’s a novel in you that is not based in Delhi?

For me, setting a novel in a particular geography only becomes possible once I feel a sense of intimacy with it, once I get a sense of how people live in that place and what specifically they are dealing with, and feeling in that space.

As such, it is hard for me to think of setting a novel in a place I haven’t lived in. For me, the idea of writing a novel doesn’t precede the creation of intimacy with a place, it probably springs from the process of creating emotional links with a particular geography.

Having said that, I should also clarify that I have never lived in Old Delhi, nor have I spent a lot of time there, but still it is the primary setting of Half the Night is Gone. It is not necessary to inhabit a place to make emotional links.

In the last few years, you’re easily the one author who has given us the most number of references from Hindi literature. Does it come naturally for you to write in English?

English is not only my first language, but also the language I am most comfortable in. It is also the language I think in. Hindi and Urdu are both languages I love dearly, they affect me the way music affects me.

When I banter with my friends from college, it is always in a specific dialect of Delhi Hindi as inflected by the language of IIT-Delhi in the 1990s. That was the dialect whose power was the engine for my first novel, Above Average. But meetings with college friends happen infrequently, so most of the Hindi I get is from day-to-day conversations at work, or from books, or by overhearing people on the street, which I love to do.

In the story, when it comes to ideas of a feudalistic society, and its remnants in the modern-day, many of us related to them in different ways. Looking around, how much of that culture is disintegrating, with youngsters more prone to voicing opinions as against settling down?

The fundamental tenets of a feudal and casteist society are still in place, I feel, although the ways that these are expressed may change with time and with the intermediation of changing technologies.

Regarding young people, I think in every generation, the youth raises the banner of revolt. Every now and then, a generation does cause a far-reaching transformation. Whether the current generation will do so or whether they will continue to articulate regressive ideals in new ways, is something to be seen.

Following the DSC Prize, have you begun to fantasize about bigger awards?

Having been shortlisted a number of times in the past, and having never got an award, my first feeling was that of relief. I was relieved I wouldn’t have to go through the aftermath of a rejection, never a pleasant sensation.

As for bigger fantasies, I’ve learned over the last 10-12 years as a published author that hankering for literary success doesn’t get you literary success, it just gets you down. Best to keep doing the work you are doing, keep following the internal logic of your own writing process, and hope that external factors align in such a way that your rejection to validation ratio remains reasonable.