Rahiman Dhaga Prem Ka, Mat Todo Chatkaye, Tute Pe Phir Na Jure, Jure Gaanth Paree Jaay.

(Says Rahim do not snap ever the thread of love, once broken, it does not unite, if it does, knots appear.)

Many of you might have studied this doha (couplet) by Rahim in school. But only history buffs would know that Abdul Rahim Khan-i-Khanan was one of the Navratnas (nine gems) in Akbar’s court, and had built a tomb in the memory of the love of his life, his wife Mah Banu near Humayun’s Tomb in Nizamuddin East in 1598. It was the first monument of love and was built 50 years before the Taj Mahal.

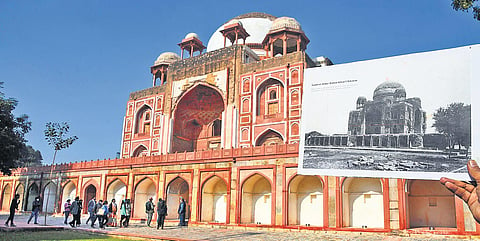

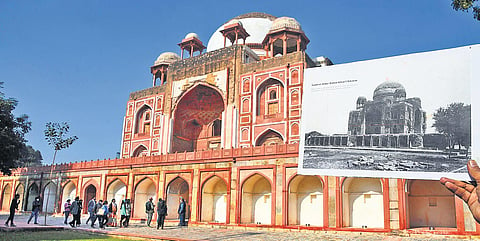

Known as Rahim’s Tomb, the mausoleum stood in ruins with a risk of collapse until 2014, when the Aga Khan Trust for Culture in partnership with InterGlobe Foundation and the Archaeological Survey of India – began their conservation efforts.

The work got completed recently and the tomb was thrown open to the public on the 464th birth anniversary of Rahim on Thursday, December 17.

AKTC CEO Ratish Nanda says, “We are doing restoration work in the Nizamuddin area. Here, we had to strengthen the entire foundation, without which this building would not have stood. In a nutshell, we did emergency conservation.”

Was a quarry in the 18th century

Similar to the Humayun’s Tomb in appearance, this tomb’s dome had been largely removed and even the canopies had fallen.

“We did exhaustive archival research, but all our evidence was at the site itself. The marble was removed from here in the 18th century, and we had to put back some of it to stabilise the base of the dome and to indicate what its original finish was,” adds Nanda.

Some elements went already missing before conservation could begin as the building was used as a quarry between the 18th to 20th century. Mostly the structure has been restored using marble and laal patthar (red sandstone), and The vaults and parapet were reconstructed using Delhi quartzite and red sandstone.

1.75 lakh man-days generated

Nanda says, “We used local craftsmen, local building traditions and local employment. Sadly, there are no craftsmen from Delhi. Since laal patthar is available in Dholpur, Rajasthan, men were called from there and for the marble, craftsmen were brought in from Makrana.”

It took 1,75,000 man-days of work to restore the grandeur of the tomb.

Geometrical and floral patterns

The principal chamber (main hall) on the first floor is largely original, adorning floral and geometrical carvings done in cement, plaster, and layers of paint. First repairs of the tomb were done when Lord Curzon took over the ASI in the 20th century.

“Back then, cement was the modern material used across all heritage sites. Only in the late 20th century we realised that cement eats up the original lime plaster. It was painstaking cleaning work as 80-85 per cent of it is original,” says Nanda.

Rahim’s love for water

Rahim patronised the construction of canals, tanks, enclosed gardens in Agra, Lahore, Delhi and Burhanpur, among other Indian cities. To the rear of the main hall are three water structures at a height of six metres from the ground.

Conservation architect with AKTC Ujwala Menon says, “We did a whole study to find out how did he lift the water, but did not find enough evidence to recreate it. So we restored these structures as it is.”

They found that the tanks would have also interacted with the gardens around the tomb. “What is now called the Barapullah Nallah, was the tributary of Yamuna.

The tomb was built along the river. We found a terracotta pipe that went straight into the foundation, which also indicates that he had planned the water system, even before he had executed the building. But going deep would have weakened the foundation,” adds Menon.

The main hall has the sarcophagi of Banu and Rahim, who was placed at the tomb in 1627. But the real graves are on the ground floor, below the sarcophagi. The main crypt is in the centre with four crypts around it. Only the main hall and crypt is open to the public, the four crypts are not. Menon concludes, “Rahim probably intended this to be a family mausoleum, and these chambers would have been for his family members.”