Islam ke log par unka jaanwaro wala kaam dekh ke mujhe itna gussa aata hai. Islam main kidhar likha hai ki doosre ke biwi ko oota ke ye karo? [They are people of Islam, but seeing them behave like animals makes me so angry. Where is it written in Islam that you can covet another’s wife and have your way with her?” fumes Feroza Haidari, 33, an Afghan refugee living at Malviya Nagar. For the uninitiated, Taliban hardliners are looking for women from 15 to 44 years to marry them off to their fighters. Haidari was eight months pregnant when she fled to India with her family in 2013 after her brother-in-law was kidnapped and released on ransom, even as other family members were threatened with the same fate. Another Afghan refugee, Razia Asas, 45, delivered her fourth child within a week of landing in India after her reporter husband started getting threats for his anti-Taliban coverage. “The Taliban are Sunnis and despise us Hazaras, as we are Shias. We still have friends there, and we are very worried for them.”

Both women work at Silaiwali, the UN refugee agency which employs Afghan woman refugees to make cloth dolls from leftover fabric. The unit is based in Khirki Extension, one of the bustling pockets for Afghan refugees in Delhi, along with Malviya Nagar, Lajpat Nagar, and Bhogal. As of March 2021, Afghan refugees account for 37 per cent of refugees and asylum-seekers registered with UNHCR India. The numbers are expected to rise in the coming months, given the country’s current socio-political climate.

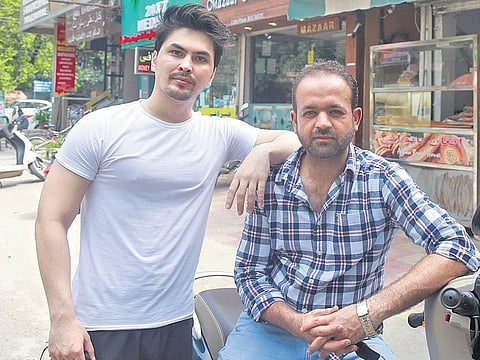

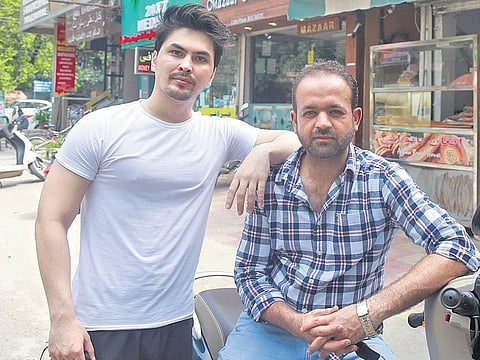

Best friends Hameed Muhtashami, 25, and Haroon Yaqobi, 35, from Lajpat Nagar, have their eyes peeled for every news update coming out of the warzone. “In Lajpat Nagar, we have access to Afghanistan news channels Tolo News and Lemar TV, and I fear for my family living in Kabul when I see the news. I call home on WhatsApp or Viber every night as the Internet speed is better then. People in my country are dying every day, either from Covid or at the hands of the Taliban,” says Haroon.

Hameed, who holds a student visa for pursuing an MBA, does not mince words for the insurgents. “So many have been widowed and orphaned, as the Taliban continues to blast mosques, education institutions, government buildings, roads, and bridges. backed by Pakistan. In addition to suicide bombers, they use magnetic bombs to destroy vehicles of most government employees. Pakistan and the Taliban are always trying to bring dispute and racism among the tribes such as Tajik, Hazara, Pashtun because they are scared of our unity more than an atom bomb. Also, we are unlucky to have bad neighbours,” he notes obliquely. Pakistan is funding the Taliban and sheltering its base camps, he says. “Both Pakistan and Iran are stalling the peace process, as they know we have the potential to develop our country. But India is with us. This is why we Afghans love India so much. I know people back home who have never visited India, but can speak in Hindi as they love watching Bollywood movies and Hindi TV serials.”

Razia remembers a normal life before the Civil War. “We lived in sukoon (peace). I used to wear jeans pants with T-shirts, salwar-suits, graduated with a BSc degree from the Afghanistan National University, and taught science to students up to Class 8.” Then the insurgent infighting became “roz ki kahani (daily affair)”, and occasionally, the blasts splintered glass and mirrors, and sent shards flying about the house, and both adults and children and take cover under the table. She remembers her joyous wedding — “we had taken a lot of photographs and videos” — but had to destroy every trace when the Taliban started barging into homes, and smashing TV sets, cameras, and tearing photos.

While Razia never came face-to-face with the Taliban, Feroza did at age 5 in Mazar-e-Sharif, when she saw them shoot a man. “I was drawing water from a well and fell down in shock. One of them picked me up, dusted my clothes, and tried to console me, saying they had killed a ‘bad’ man. I came home and howled for an hour.” After a year, the Taliban picked up her father and his cousin from their farm and imprisoned them, she says. Her family fled, and during the three months they walked to their hometown in Bamiyan, they wore the same set of clothes and ate from leftover plates of food on the streets by those also fleeing the Taliban. Her father was released when the family coughed up a bribe, and they all fled to Pakistan in 2000, then returned to Afghanistan in 2009. But it did not end there as Feroza fled again — this time to India — after a kidnapping threat.

In an attempt at bravado to speak to at least one insurgent and make them see light, Hameed tried to interact with a group of Islamic Emirati [what the Taliban identity as] that he spotted in Paghman on Eid, three years ago, when the customary ceasefire was observed for the occasion. “We youngsters call them ‘brother hai naarazi’ — upset/unhappy brothers — not the Taliban. I greeted them that way, and one of them laughed. I wanted to go back to meet them, but as always they violated the ceasefire and we were stuck indoors. “

Despite holding an AADHAR card, bank account, and driving licence — legal amenities that most refugees in India have been unable to do so — Haroon is struggling to find a permanent source of income. “My Indian friends helped me secure job interviews, but I would get rejected on showing my refugee card.” He even opened a store for imported dry fruits, tried his hand at an import-export business, but then came the pandemic. The Covid-issue travel ban also killed his other source of income as translator and guide for Afghan medical tourists coming to India. He would pre-book appointments, guest rooms around Lajpat II, and schedule tourist attractions if requested. “I know doctors in every area of specialty and reasonably priced clinics. The patients would pay me anything above 5K before their return.” Now, his family sends him money to tide in these zero-income days, but despite these hurdles, if given a chance, Haroon is willing to take Indian citizenship “because the people here are so lovely and non-interfering.”

Unlike Haroon and most refugees in India seeking residency status in the US or Canada, Hameed wants to seek employment in Afghanistan after his course ends in 2022. This despite rushing to India after his father, a former civil servant, was issued kidnapping threats by warlords and the Taliban. “India, being the largest democracy in the world, living here is a dream for citizens of Middle East countries that are a warzone. But my country needs young, educated people like me. My family disapproves this decision, fearing for my safety, but I will convince them.” Hameed also feels privileged with a student visa, as he can exit or re-enter the country without a hassle. “But given the success of Digital India plan, I wish the Indian government allows refugees to at least avail of online money transfer and EMI services.”

These are two of the many issues that Razia and her family continue to battle. Her eldest two dropped out in Class 8 when the fees became unaffordable, and now take online English tuitions from home as an added source of income. The restaurant her husband was working at shut shop in the pandemic, and since then he is without a job. Razia still gets paid via cheques, which she encashes at the bank after showing her refugee card.

On the 19th day of their landing in India, Feroza’s father-in-law went missing, and the family fears he was kidnapped by the African contingent, back then a sizeable population in Saket. “Our landlord let us open a restaurant on his name, but after two years the business failed.” Feroza went into depression and was put on medication for two years.

Her husband and brother-in-law are still jobless, her sister-in-law works as a restaurant cook, while her kids aged 10, 9, and 8 are completing their education online. She works as a part-time cook and at the center, makes cloth dolls and knits. Feroza says as Pakistani refugees, they were allowed to buy a house, open a bank account, get a driving licence, and complete higher education, “but if we took the identity card (CNIC, Indian equivalent of an AADHAR card), we could not leave Pakistan.”

She has exhausted every possible option to give her family a better life here. “Our house has no curtains and rugs, because all our lives we have been running, and leaving everything behind. Only my life has been my constant.”