There is always a hammer about to come down on a piece of metal, a block of brick, or a sheet of iron in Patparganj. One deadbeat building or warehouse goes down, another comes up— other than that, not much moves. Digital creator Prateek Arora, 33, who grew up in the ’90s in this East Delhi neighbourhood, has put a rocket— but not in every frame—in the middle of his fictional town.

‘Rocketganj’ is modelled on Patparganj. Through it, Arora explores another ‘new India’ story, part of his constant thought experiments with image and technology in which the human being is usually seen a little out of step, or creeped-up, about the future. Sometimes they are the horror element in his visuals—in a family album, a veiled ghoul is a relative among other relatives; smog spirits, who were once humans, teeter around neighbourhoods with faces afire; a half-werewolf ’s other half is a woman in a night-dress.

According to his Insta feeds, some of these were created at 2 am. Rocketganj, the title of the exhibition at the Photoink gallery, which has hung 36 AI images, was, however, created in the unflattering light of day. “Rocketganj may not have been inspired by a beautiful or a curated part of Delhi, but I’ve filtered it through my pop-cultural references. It is but the first chapter of a story, and I’ve just arrived in it. It’s my sandbox,” he says.

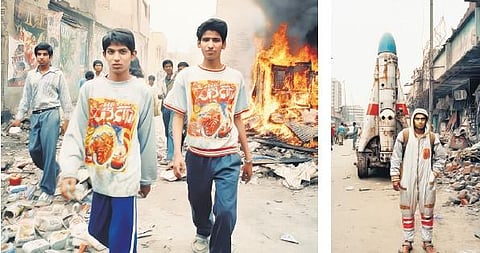

Arora imagines it as a suburban town across the Yamuna where the main livelihood is the making of rockets. The flip side of this being its economic engine is the danger of people living among rockets as they whiz overhead, or crash, or fail—evoking the picture of a William Gibsonian disaster, where ‘the future’ could be the evil twin of a present-day world that is trying to go hi-tech, where too many things are being tried with ‘progress’ as a thumb rule.

Many questions

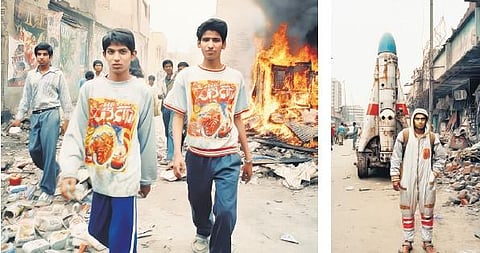

Arora says he is hedging his bets on this. “I’m just posing a question, trying to explore what happens if you turn a knob this way or that,” he says. In Rocketganj, he has shown some of the kids as angry, their faces pulled in a grimace as the sky lights up overhead with zooming rockets, or they tie themselves up around one in brutal protest in a suicidal mission. And yet there are some who are alright with going with the flow—aping astronauts, making the space flight a part of everyday fashion or business.

A discarded rocket, for instance, becomes a kiosk to place tea-coffee items for a young vendor in Rocketganj. “In Rocketganj, there is a programme for children of parents who are workers at the rocket factory. If they excel, those kids get a shot at being astronauts–so it does have a fable-like premise though I wasn’t thinking of happy endings like in a Pixar movie. The place has people who are aware of discrepancies,” says Arora.

Tech and the nation

Arora, who now stays in Mumbai, is VP, Bang Bang Media Corp, a broadcast and storytelling company. He says he is drawn to tech as an index of capturing change. A millennial of the post-liberalisation age, he describes his generation as people who “grew up with a different taste profile, from having nothing to watch on TV to television with Dexter’s Lab [a hit Cartoon Network animation series], mutants, superheroes…. We have really seen life and culture change in the last three decades but not that big a conversation around it, which is surprising given our obsession with science and technology”.

This is because unlike America where technology was part of a post-War boom that eventually established their supremacy with NASA, India’s origin story was about gaining self-respect and independence after being a colony, he says. For Arora, ISRO’s Chandrayaan seems to be an important reference. At the meeting in the gallery, he wore a sweatshirt with an ISRO monogram. Arora also describes himself as a “world builder”. The stories he puts up on Instagram shows that he wants to build a conversation around South Asian settings. His cyborg woman wears a bindi. His aliens are in Made in Heaven ensembles.

In Rocketganj, he points out, he did not give it a Hollywood direction and make things sleek, but rather kept them real. “The boys don’t look like Ironman and I’ve placed them in a realistic East Delhi setting versus a futuristic hangar from an escapist space sci-fi movie.” Arora also puts himself in the world he builds. In Rocketganj, he is the middleclass boy in a hoodie beside a pile of bricks—not the boy who will chuck stones; for, he does have in this series, some boys who look as if they will. Arora is perhaps looking for India’s foundational story in art— not in a dystopia but in a world of equal opportunities.

‘Rocketganj’ is on at the PHOTOINK gallery,Vasant Kunj,till December 2.