Windows shape the way light falls inside the room. In Mughal-era buildings, the relationship of light with shadow, between man and God, was mediated in no small measure by the jali. On World Architecture Day, Navina Najat Haidar’s work of documenting the perforated stone or latticed screen found in palaces and tombs, in hamams and mosques, throws the spotlight on this ubiquitous yet hardly talked of ornamentation of Mughal architecture. And it has travelled well—through the Gujarat Sultanate and the Rajput kingdoms to central India and, also in the south, in the Deccan.

Haidar is the chief curator of Islamic art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art(MET) in New York. Her new book, Jali: Lattice of Divine Light in Mughal Architecture (Mapin), explores the delicate beauty of more than 200 jalis across India, from 17th-century examples in Agra to those designed by global contemporary artists influenced by historical styles to the private quarters of an American heiress. The model mostly followed everywhere was, however, guided by Mughal aesthetics.

Jalis in the buildings of Akbar and Jahangir showed preference for“geometric patterns evolved in the wider Persianate world”, says Haidar in the book. They also borrowed from auspicious Hindu and Jain motifs such as floral heads and swastikas. These perforated screens also had other functions—they were often the point of encounter between two communities, the Hindu and the Muslim, especially in Sufi shrines. Threads were tied on the jalis of the shrines to pay homage after a prayer had been answered or to submit a new prayer or to seek blessings. God, and an interest and an understanding of ‘the other’, lay in these details.

Excerpts of a conversation with Haidar:

How did you come up with the idea of an entire book on jalis? It is quite a lateral entry into the world of Mughal architecture.

The study of architecture incorporates a focus on elements of design, ornament and function as well as a consideration of the edifices as a whole. This volume places the jali within the larger language of Mughal ornament and architecture, while also drawing out the individual story of this feature in different contexts.

How was the jali interpreted in different regions of what we now know as India and the reason for its pan-Indian popularity? Which stone is most conducive to the crafting of jalis?

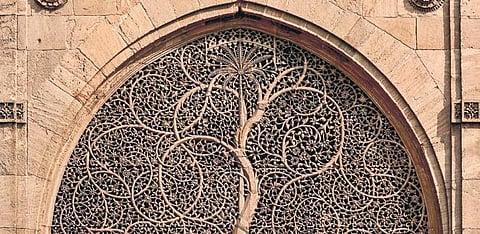

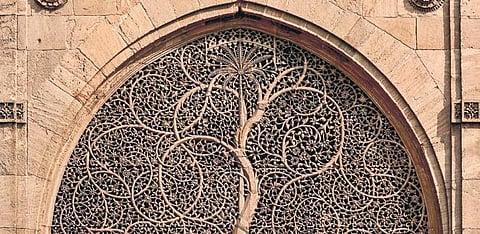

In historical structures, the jali may be carved in materials such as marble and sandstone, depending on the monument and the desired function of this feature. It can range from exquisitely carved elements - such as the ‘Tree of Life’ jalis in the Sidi Sayyid Mosque in Ahmedabad - to large-screen walls enclosing a sacred space in filtered light and celestially-inspired patterns - such as in the shrine of Sheikh Salim Chishti at Sikri.

For women on the other side of the jali were these hindrances to looking out?

Harem spaces were often screened so as to keep the women’s quarters private, but offered views outward.

How did God enter the equation when it came to jalis? There is reference to ‘divine light’ entering through the perforations of the windows.

The Mughal arts developed a sophisticated language of light symbolism and allusion, which is apparent in the ways in which jalis were designed and used. Celestial imagery in Mughal art exalted the power of the sun and the mysticism of the stars set in the heavenly sphere, which were evoked in the radiating sunbursts (shamsas), stellar (sitara) shapes and geometric knot patterns (girih) of jali windows and screens. The motifs of divine illumination were integral to Sufism as were allegories of light in Islam, such as the ‘Verse of Light’ where God is likened to a light from a lamp in a niche. In Mughal tombs, mosques and palaces, jalis mediated between heavenly light and the world of man through a sophisticated language of mathematical patterns, reflections and shadows.

The British too seemed to have been inspired by jalis. Why?

The jali was not a major feature in the architecture of the Raj but you can see interesting ones in Rashtrapati Bhavan, which combined old and new influences into distinctive styles such as lyres or star nets.

Which are your personal favourites when it comes to jali work in India?

I appreciate the great Mughal jalis of the Shah Jahan period, such as the openwork vase jalis in the Agra fort, which show superlative carving and European influence. I also like the ones in the National Museum building - which is about to be tragically demolished, according to reports. There are handsome, starry and medallion jalis in the inner courtyard, which is an attractive circular space containing sculpture and greenery.