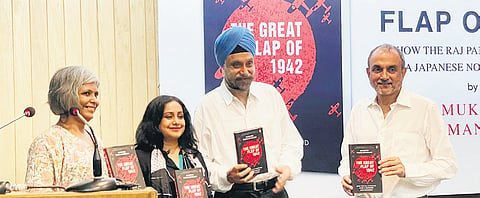

In many ways, Indian history writing is yet to come out of the Forties. Seen as the decade that delivered Independence, documentation of that time is usually in the nationalist mode. But there have been exceptions. Janam Mukherjee’s Hungry Bengal on the Bengal famine of 1942-1943 is a searing account of the tragedy that looks beyond ‘shortage’ of food by linking Britain’s imperialist strategies with the ravaging of the Bengal countryside – its pursuit of a scorched-earth policy in anticipation of a Japanese invasion and its indifference to human lives evident in the way it dealt with the dead bodies that piled up on Calcutta’s streets. Mukund Padmanabhan’s The Great Flap of 1942 (Penguin India), which celebrated its publication recently in the city, is an interesting and briskly paced account with the same players.

A veteran journalist and now a professor at KREA University, north of Chennai, Padmanabhan brings a keen eye to the tragic-comedy of a “non-event” – a Japanese non-invasion that nevertheless made the British Raj panic. Writer and former ambassador Navtej Sarna, who was in conversation with Padmanabhan at the event, pointed out how “you say 1942 and everyone says Quit India…”. The reason why the story of the “flap” – that is how British bureaucrats described the panic – and the mass exodus that followed all across India fell through the cracks is because it does not “fit in the grand narrative of India’s independence or decolonisation”, explained Padmanabhan.

The book is rich in little-known details, especially how the Japanese threat played out in the minds of British India governors, Indians, and local administrators, and how that prompted the fright and flight with almost entire cities emptying out, disrupting lives and livelihoods.

Pandmanabhan’s interest in the subject was piqued by the stories of his mother, who, like many others, fled Madras with her family in the last wave of the exodus to Coimbatore, returning to find their home ransacked, and her Intermediate degree unfit for a college she had applied to, which asked her to do the first year all over again.

Coastal areas such as Madras were also spooked by what they saw as British incompetence in matters of defence in the light of the bombing of Vizag and Colombo, and bizarre experiments being carried out in Delhi. John Bicknell Auden, brother of the famous poet WH Auden, and an official with the Geological Survey of India, set up braziers around South Block and filled them with tarry substances to drive up clouds of smoke, said Padmanabhan, in order to “obscure important buildings” from Japanese air attacks.

The Madras Governor’s Pongal day (January 14, 1942) message linking the fate of Singapore — which was to fall to Japan a month later—to that of Madras, was also an example of confused messaging and, in fact, triggered panic, said the writer. The Madras Corporation even donated `10,000 for Singapore, so crucial its security was seen to be for the security of Madras.

Though Japanese air raids would come a whole year later, the government of Madras, in a communiqué dated April 11, 1942, sounded the doomsday siren and advised residents other than those engaged in “essential services” to leave the city. Panic buttons were similarly pressed in Jamshedpur, Cuttack, Cochin with the colonial administration actively encouraging, or not discouraging, “non-essentials”, “non-effectives” or “useless mouths” from leaving. These included the “dangerous animals” in the Madras Zoo; a paramilitary force, which had crushed the Moplah rebellion of 1921, was drafted in to shoot them down. To these lost stories, Padmanabhan’s book also sheds light on divisions in the Congress about various attitudes to WWII – in how to support the war (or not) in exchange for freedom from British rule.

Padmanabhan’s book also asks the question whether the great flap, considering that it was brief, was painless. What was the extent of the impact of the Japanese threat on India’s freedom struggle in the year 1942? Were the shouts of ‘Quit India’ stronger because of Japan’s entry into South Asia? Would Japan have aided Indian independence? While Padmanabhan says he does not have a “firm position” on the last, the book will satisfy every anti-colonial heart that will know about a time when the famous Brit stiff upper lip visibly quivered, and, instead of taking charge, the Raj did the easy thing: hit the panic button.