As a four-year-old, Zeyad Masroor Khan had once flipped a switch, not attached to any switchboard and hanging down from wires, near a window, in one of their rooms, that overlooked the Hindu area near Upar Kot, a Muslim ghetto in Aligarh’s old area. For a while, nothing happened. No lights came to life, no fans turned on. And yet moments later, he heard, “The Hindus are coming”.

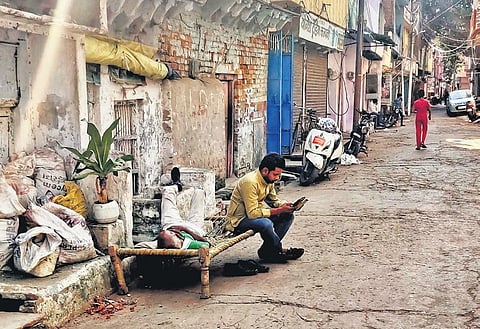

Khan, 34, now a journalist, learnt that day that an innocent act of flipping a switch could trigger a communal riot. Far from the romanticised image of it being a university town and the home of poets, Khan’s Aligarh had narrow lanes filled with violence; here he had learned to use pseudo-Hindu names to enter the ‘Hindu part’ of the town. Nevertheless, it is a city he finds strangely comforting and he is “madly in love” with it, writes Khan in his recently published memoir, City On Fire: A Boyhood in Aligarh (HarperCollins). With this memoir, Khan traces his life as a “time traveller” from Aligarh to Delhi and back and how the city’s tryst with violence and its normalisation have shaped him. Excerpts of a conversation with the author:

What made you write a memoir and why did you choose to write from a child’s perspective in the first section of your book?

The story was burning inside me, waiting to come out for at least five years. Most people in small towns like Aligarh and in Muslim ghettos have dramatic lives. I wanted to write it because so little had been written on growing up in a Muslim ghetto. However good their intentions might be, when someone else tells your story, you unwittingly turn into an object—mute and powerless without the means and spirit to tell your own. That’s why it becomes critical for writers from marginalised groups to tell their own stories.

A child can often say things adults can’t, as adults are way too afraid of society. In most of my reporting for Reuters and Vice, I have tried to bring the stories of my subjects with empathy. But for some reason, I was afraid to extend the same kind of empathy to myself. Immersing myself in the perspective of a child was also an attempt to escape the grim realities of the present world. I am a bit of an ostrich that way — escaping to my mind when the world becomes unbearable.

Your book felt like a journey that balanced seriousness with moments of levity.

Writing this was an utterly traumatic and therapeutic experience. Conveying the process of normalisation of violence sometimes came naturally while describing the events with honesty, sometimes it was deliberate. For example, I did deliberately bring up incidents of violence when I was describing my mundane childhood — it had to be naturally woven in like it was nothing special for us. Often, if one chapter was slow, the subsequent one was pacy. I had to immerse myself in the mood of the chapters.

How did you approach writing about your family, especially Saad, your elder brother? Did you ever feel the need to withhold certain information?

Writing about my own family seemed like a dangerous task. I had to be truthful and unbiased towards them and myself. Sometimes, I just wrote what I remembered, and at other times, I tried to empathise with their side of the story. The good and, probably, the bad thing about my family is that we are brutally honest with each other most of the time. Saad wouldn’t shy away from the reality that he’d bully and beat up children at his school and home. But at the same time, as a writer, I had to be fair to him. So, I made myself accountable for the times I had been irresponsible. Honestly, I was very afraid of how they would react upon reading the book but until now they have taken everything rather sportingly, a storm might be brewing in silence, though. I have held back many things to respect the privacy of my near and dear ones, writing only the anecdotes which were important for the narrative of the story and my evolution from a child to a youngster.

You describe yourself as an “arrogant” kid shaped by Aligarh experiences, where does this individual now stand amidst the normalisation of violence and the aspiration to become a journalist to report that violence?

I am now a very practical person. I do try to fight the normalisation of violence within my psyche, but I do also aspire to change things, in a very realistic way, thinking of myself as a cog in a big wheel, and not a saviour or messiah of some sort. I am not a politician or an activist. I am merely a writer who documents what he sees.

How did you approach the victims, considering the challenge of sharing their information publicly, for the book?

Most were neighbours who were rarely approached to tell their side of the story, even by close family members.So, they were very forthcoming even when told this information would be put in a book. “At least you are talking about this. Nobody does now,” one person told me. They told their stories and I just listened.

In what way did being in Delhi make you rediscover your affection for Aligarh?

Delhi, for me, symbolised an escape from Aligarh, offering me freedom, new friends, the pursuit of dreams and economic opportunities. As a student at Jamia Millia Islamia, I met people from diverse backgrounds and expanded my horizon and social skills.I also saw Delhi as a place where humans are not valued just because of their humanness, people were often valued only for their utility. After

seeing this side of Delhi, I began to value Aligarh and its innocence, the value given to human connections, and most importantly, its slowness.Delhi made me realise that I was madly in love with the warmth of Aligarh.