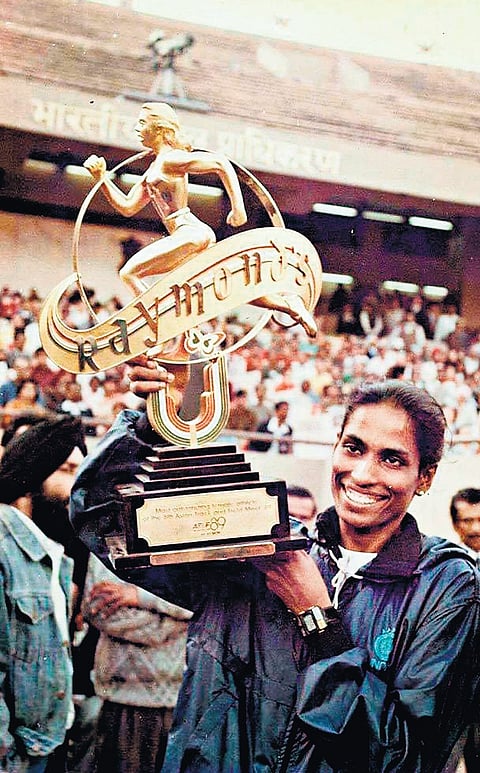

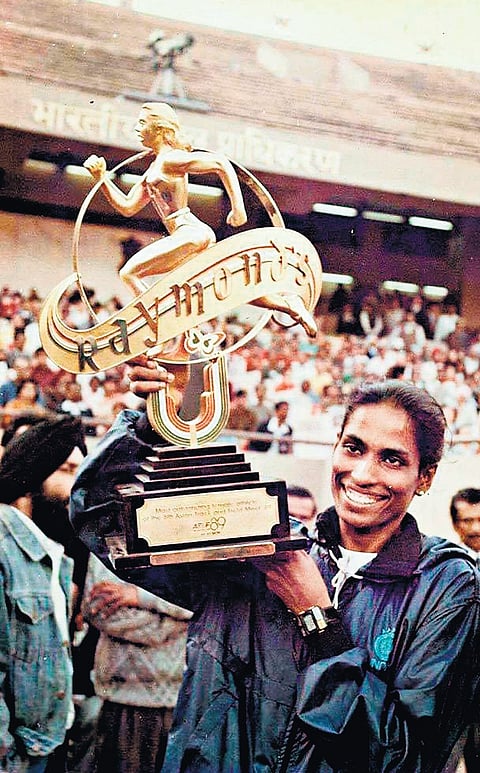

A girl running around like a boy,’ the neighbors used to say of Indian middle-distance runner Pinki Pramanik while she was growing up in the riverside village of Tilakdih in West Bengal. They felt that it was obscene. So, she would train herself at night instead, out of sight, running on the sandy shores of Subarnarekha. Pramanik won a silver medal at the 2006 Commonwealth Games in Melbourne, a gold at the Asian Games in Doha and three golds at the South Asian Games in Colombo that year.

Women running is still a rare sight in India, except when they are on a track, in a stadium. Here, no one goggles at them; they don’t have to be concerned about their outfits or their ‘domestic duties’. They are training to excel so as to win a medal and make the nation proud. Or secure a government job.

As a “hobby runner”, journalist Sohini Chattopadhyay, who is now settled in Kolkata, noticed early on that she along with a handful of other women who were out jogging in Delhi were “unusual figures”. She could never shake off the feeling that she was out of place, always hesitant to ask people, especially men, who seemed so irritable, to make way. She had to stick to running inside the boundaries of residential colony parks.

The Day I Became a Runner: A Women’s History of India through the Lens of Sport (HarperCollins), Chattopadhyay’s newly released book, is a chronicle of the lives of eight women athletes, including Pramanik, and a Maharashtra school’s athletics project, which act as a window into her exploration of questions regarding women’s citizenship in India, the politics of space and the public sphere.

A regular runner for over 15 years now and someone who finds it “meditative” after she started running to cope with the grief of losing her grandmother, Chattopadhyay interweaves personal accounts, history and thorough reportage in sketching intimate portraits of the eight women—Mary D’Zousa, Kamaljit Sandhu, PT Usha and Lalita Babar, are some of them.

The sporting lens

The idea for the book, says Chattopadhyay, was birthed in the “collective anger” she witnessed after the gang rape and murder of a 22-year-old paramedical student in Delhi in 2012. “I wanted to go out and occupy space in the world. Put me on view and say ‘I exist- so get used to me’,” she says about answering the “inevitable question” that comes up in our patriarchal societies after women are assaulted in public about what she was doing there. She wanted to explore the relationship between women and public space in a “viciously gendered” country like India, and sport proved to be the perfect lens to look at it through.

“Sport is a project of nationalism. It offers women a solid, respectable reason to put themselves and their bodies out there in the world: for national service…sports appear to bestow a higher degree of citizenship in the public sphere to women,” Chattopadhyay writes in the book.

Sport and gender

The book touches upon a gamut of issues ranging from female foeticide to sex tests in sports. Researching and writing about the three athletes--Santhi Soundarajan, Pinki Pramanik, and Dutee Chand--“who were called out for not being women”, was, for Chattopadhyay, the hardest part. “The science of sport and the science of sex is complex. And sophisticated. I wanted to make people understand the complexity of it without prying into anatomical studies or intruding into the athlete’s sense of privacy,” she says.

Santhi Soundarajan, one of the finest middle-distance runners in India, was disqualified from the Asian Games of 2006 in Doha over a sex test in which she had failed, which also effectively ended her career as an athlete. “To this day, no report of what was tested has been given to anybody, including Santhi,” says the author. In the chapter titled, ‘The woman who was erased’, she talks about how Soundarajan, a Dalit woman from Tamil Nadu, was abandoned by the Government of India and the entire sporting establishment. Despite the social stigma and threats to her due to her identity, Soundarajan still coaches youngsters on the track. “Santhi epitomises the spirit of sports, of striving,” says Chattopadhyay, who has also dedicated the book to her.

Accidental feminists

The book also gives due credit to a line of men, the “accidental feminists”, like Usha’s coach OM Nambiar or Babar’s Bharat Chavan or Chand’s Nagapuri Ramesh, “men who had somehow escaped the endemic patriarchy of the subcontinent” and felt that the young women who came under their supervision had the same promise as the young men under them.

Recalling times when walkers in a Delhi residential colony park made way for her, seeing her running, saying that she was their “PT Usha”, Chattopadhyay notes, “We can run because she ran so well”. The book is also a homage to these women who, despite monumental odds, had kept at it, for whatever reason or desire, setting precedents for young girls who find themselves exhilarated in sprinting at full speed and leaping over hurdles.