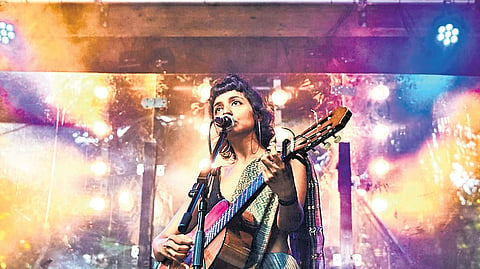

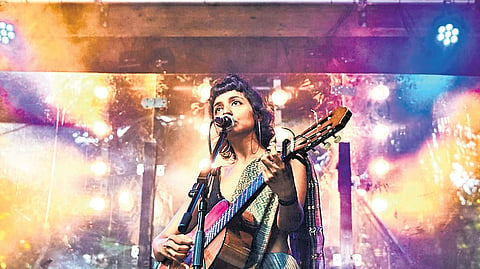

When I sing parvaton ki khamoshi ko samjhon na tum buzidili (don’t mistake the silence of mountains for weakness), I’m speaking of freedom from all kinds of oppression,” says Aditi Veena, popularly known as Ditty. The Delhi-born, Berlin-based artist is a presence in the Indian indie music scene with her atmospheric soundscapes and haunting reflections on environmental crises and social justice. In India to tour with her recent single, ‘Azadi’, whose video was shot in the Aravalli Biodiversity Park near Delhi, the melancholic anthem calls for liberation not only for people but also for nature and all oppressed beings. The track is part of her upcoming album, Kaali.

From Delhi to Ceylon

“It’s so easy to put someone in a box and say, ‘Oh, they’re an environmentalist; it’s their problem to talk about,’ and then keep working as if these issues don’t affect you,” Ditty says, reflecting on her path. “But I’m just engaging with my times. I’m choosing not to always write love songs.” She acknowledges the influence of artists like Bob Dylan, Joni Mitchell, and The Carpenters in her journey. At 13, she was inspired by a senior who performed a Carpenters song for a crowd of 12,000. “I still remember her, so shy, but as she sang, it cut through the crowd. I thought, I want to do this, too.”

Ditty has always dreamed of being a musician. “I dreamed of being a songwriter, but not for Bollywood. I wanted to write my own songs and sing them,” she explains. Her young adult years in Delhi were marked by the loss of her father to a lung disease—a painful reminder of the city’s toxic air and environmental neglect. This experience brought home the urgent realities of climate change in South Asia. “Our postcolonial reality became pretty evident,” she says. “I realised our cities are under so much pressure, and I didn’t want to practise mainstream architecture. It all felt so messed up.”

Architectural education gave her an early understanding of how South Asian cities have inherited infrastructural struggles rooted in a colonial past, but she grew frustrated with her field’s narrow focus. “In university, if you wanted to use bamboo or build with mud, to go back to traditional ways, it was always considered an alternative,” she recalls. She eventually moved to Sri Lanka to work on restoration projects with renowned architect Geoffrey Bawa, hoping for a fresh start. “I thought I’d escaped it all—the pollution, the rush, the maramari—but Sri Lanka had its own brutal realities,” she reflects.

While working on an independent project with Nike, she was struck by the environmental cost of the fashion and dyeing industry. “The clothes we wear are all dyed with chemicals so toxic you can’t put them in the ground or release them into the air without risking severe environmental harm. In places like India, Sri Lanka, and parts of Africa, massive wells are dug specifically to bury this waste, and many European companies outsource their waste here. I thought, I can’t be part of this. I started thinking about how I could reshape my life to be a better influence, and that’s when I began writing songs,” she recounts.

Her pain and observations materialised in her debut album, Poetry Ceylon. Through her songs, Ditty expresses her love for nature and voices the urgency of environmental issues. “My most famous song, Deathcab, is a love song,” she says, “but I have written a lot about the cities, about forests and oceans.” Her producer recognised the environmental themes, calling them “Earth songs,” which inspired Ditty to embrace her role as an environmental artist.

“Delhi is always present in my work,” she says. “There’s a song in Poetry Ceylon called ‘Eulogy for a Sparrow’, where I talk about how the sparrows went away. It’s a reference to the changing face of cities like Delhi, where pollution and urban sprawl have erased the natural world I once knew...Bengaluru, Chennai, Kochi—these cities are choking. We built over lakes and rivers, and when it rains even a little bit, cities just shut down. My father used to tell me about lakes in Dwarka, Delhi, that are now gone.”

A call for freedom

Inn vadiyon ko jeene do (Let these valleys live), was the first line Ditty wrote for Azadi. “I was writing about Kashmir, but also about letting live, the idea that we are a country that came up with non-violence. What happened to us? I wanted to write about letting live, being peaceful to each other, to women, to children, to the elderly, to people of all castes, to nature,” she says. Her inspiration evolved from this line into a full melody, and Azadi became her first song in Hindi, marking a return to her roots. “In Hindi, a mountain becomes a parbat, and there’s weight in that word, a heritage. I was surprised by how strong that felt.” The song is then both about liberation and about a homecoming.

A fascination for choirs led her to collaborate with Youth for Climate India, a climate activism collective based in Delhi. “Singing together is something I’ve always loved,” Ditty shares. “I wanted to bring that sense of solidarity to this song.” The sounds in the video were recorded in nature, giving the music an immersive quality.

Navigating the industry

As an independent musician, Ditty balances creative freedom, recognition, and financial stability. “The life of an independent artist is tough, especially if you’re not constantly on tour,” she admits. Her eco-conscious lifestyle reflects her values: she buys a single round-trip ticket from Berlin to India, explaining, “I’m trying to build a rhythm where I tour in Europe in the summer and India in the winter.” This approach aligns with her environmental goals. “It’s about setting limits in sync with nature.”

Regarding the music industry and platforms like Spotify, while recognising their reach, she notes, “Spotify has been reducing payments to artists. I have millions of views, but as an artist, I barely see any of that revenue,” she reveals. Despite the viral success of her earlier song ‘Deathcab’, which garnered over 4 million streams, financially the returns were less, compared to the publishers, producers, and the platform itself.

Ditty sees herself as an “artist of the times,” compelled to address these issues in her work. “It’s hard to stay motivated, especially with the numbers game. Validation today comes from metrics, which are often manipulated. But I don’t censor myself,” she says. “I won’t compromise on my art or my message.” Through her music, she has carved a space for reflection, resistance, and connection. Singing ‘Azadi’ in Hindustani was a breakthrough for her. For Ditty, her journey is as much about finding her voice as it is about helping others find theirs.

For tickets to Azaadi India Tour visit ditty.co.in