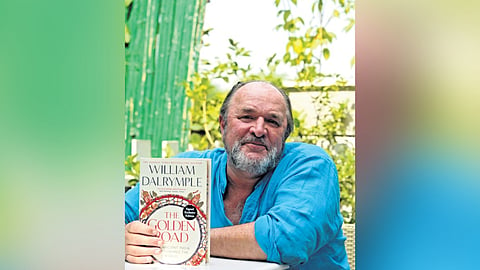

India has not been just a career for author William Dalrymple. He has engaged with it and particularly with Delhi from the peripheries, from its centre, and has followed its various masters and power flows through the centuries, with affection and empathy. The principal pleasure of his books, however, are the characters who might have wilted and become the ghosts of history had he not put them at the centre of his storytelling by crafting a narrative from available archival material. For The Golden Road: How Ancient India Transformed the World (Bloomsbury), his first history book outside the 18th or the 19th centuries, the challenge he faced, compared to the Mughal period or when he was working on the East India Company books, was of too few sources. The argument at its heart is an interesting one. It points to an Indosphere—the spread of Indian music, dance, mathematics, architecture and sculptural ideas for over 1,500 years (250 BCE – 1200 CE) across a vast area of Asia, acquiring local forms. Excerpts from a conversation with the author on the day of the launch of his book in Delhi:

City of Djinns, White Mughals, The Last Mughal. You’ve had quite a medievalist’s focus. What made you shift to ancient India?

The ancient world was always an original interest. My first trip to London from Scotland at about seven was to see the Tutankhamen exhibition. Every summer, I went around working on archaeological digs at Orkney, Dorset—archaeology has always been an abiding interest. What interests me about it? It’s a very exciting world of distant history. In fact, my teenage self would have been quite surprised that I spent 20 years writing about the 18th century, it was always the period my father loved most. My childhood was spent being dragged around 18th-century houses screaming to be taken to a stone circle or some ancient site.

When I first came to India, I visited the Ajanta and the Ellora, and it was much later that I got excited by colonial history, the East India Company and its interaction with 18th-century India, and the late Mughals. I worked with my sadly deceased friend Bruce Wannell on four Company books. But for the ancient period there was a lot more scrabbling around with epigraphy, coins and sculpture —it was much more fragmentary. Bruce was a great Persian scholar—he had this incredible ability to read late Mughal Persian, which is not like modern Iranian Persian; it’s closer to Dari in Afghanistan. So, I knew the history, he knew the language.

The Golden Road is long overdue, it is the first time I have written a history book outside the 18th or the 19th centuries— I have written scholarly articles on it in journals and magazines, though—and it’s a lot more difficult because there are such few sources.

Wu Zetian is a remarkable find of the book—a Chinese ruler quite sold on the geo-cultural region that is now India, importing from there not just Buddhism, and making it the state religion, but also appointing ‘Indians’ to positions of prominence in her court.

Not just Wu Zetian, but other rulers of east Asia were giving Brahmins and monks prominence in court because they introduced written scripts and numeracy. As for Wu, she wanted power in a Confucian system that doesn’t give women power. She relied on the Nalanda monks to give her legitimacy through Buddhism -- they came up with bogus prophecies anointing her Maitreya, a future Buddha. Their place in court came from their usefulness and not just because she loved Indian culture.

In your book in some places, you have used India and Indic interchangeably or switched between Hinduism and Shaivism while we know that it is only through the encounter with the East India Company and its conquest of Bengal that ‘Indians’ began to think in terms of India as a nation-state. Prior to that this was thought in terms of a far more variegated Indic civilisation.

There has always been a very clear idea of India as a single geographical, cultural and sacral unit. When Alexander the Great turns up here, in Roman geographer Strabo’s account, the sadhus give him a very clear answer of their homeland, as one that is bounded by Indus on the west, the Ganges on the east, an ocean in the south…. When Xuanzsang enters Jallalabad in 7th century CE, he says, I’m entering ‘five Indias’ made up of ‘more than 70 kingdoms’ so this was recognised as a coherent cultural unit by both insiders and outsiders, and it doesn’t matter that, unlike China, it was not a single political unit. But it is true that it is only with the advent of the East India Company you get ‘India’ as a single political unit.

The Silk Road is commonly thought to be a network of trade routes connecting China and the Far East with Europe. You say it’s a myth. Please elaborate on this, and also do detail what is the arc of the Golden Road? Is the Golden Road your invention?

Yes, the phrase 'Golden Road' is my invention and with it I have tried to express what to my mind is a more accurate account of ancient trade based on India as the centre rather than China. In fact, the Romans and the Chinese had no idea about each other’s existence. No single Roman coin hoard was ever found in China; Rome and China simply did not trade with each other. On the other hand, southern India and Sri Lanka were the largest trading partners of the Roman empire and there is ample proof of that.

Ferdinand von Richthofen, a German geographer and traveller, is credited with popularising the term ‘Silk Road’ in 1877. The Silk Road didn't enter English before 1936; in the 1980s it became a popular phrase. Now it’s almost an academic fact but it simply isn’t true before the Mongols created a highway running East-West between the Mediterranean and the South China Sea in the 13th century. A Silk Road trading with the West is a myth in the classical period. And yet, there are two exhibitions in London this month about the Silk Road and both almost completely ignore India."

The Silk Road only got going in the 13th century when the Mongols smashed through the middle of Asia and linked the Mediterranean to the South China Sea. So, Marco Polo in 13th century could move from the Mediterranean to Xanadu without leaving the Mongol empire so at that point the Silk Road was a real road moving from East to West. But in the Roman period, there was no direct East-West trade at all. But there is plenty of evidence of traffic between India and the West.

Strabo visited a port where 250 vessels left in a great fleet to go to India. And Pliny, a famous Roman naval commander, talked of how India was ‘the drain of all precious metals of the world’. The Muziris Papyrus, an invoice of an Alexandrian importer that has survived, is another astonishing document of proof. Here is an inventory of not only all objects, including 2 tonnes of ivory and pepper, he was importing in a single first-century ship from India, but it also gives the prices and custom rates, and shows that had this container reached its destination safely, it would have generated enough cash for the importer to buy one of the largest estates in Roman Egypt or Tuscany with enough money left over to join the Senate.

The Golden Road gets going in my view with the Roman conquest of Egypt -- the Battle of Actium with the death of Marc Antony and Cleopatra leads to the integration of Egypt into the Roman empire and you had ships sailing in both directions. So, 1st century BCE to the 5th century CE is when the western branch of the Golden Road was at its peak. Then Rome collapses and you have Tamil trading guilds turn eastward majorly from this point and ships start moving through the Malacca Straits to the Mekong Delta, and eastern ports open up, and you find wooden Buddhas turning up in Thailand, Malaysia, and Shivalingams in Vietnam, Cambodia. And suddenly, you have south-east Asian chieftains giving themselves Sanskritic names with their temples growing larger than any in India such as the one in Borbudur (Indonesia), the largest Buddhist monument in the world, and Angkor Wat, the largest Hindu temple in the world and ten times the size of any temple in India—all this pointing to an Indosphere where Indian music, dance, mathematics, architecture and sculptural ideas spread for over 1,500 years (250 BCE – 1200 CE) across a vast area of Asia acquiring local forms.

In fact, when Tagore visits Angkor Wat he remarks: “Everywhere I see India but I cannot recognise her.”

The Indian right looks at the ancient Indian civilisation and sees the modern nation-state as its continuum. Do you think The Golden Road has certain strands that run the risk of a similar reading?

There is a view in India that those who write about the Mughals are somehow Marxist Lefties and those who write about ancient India are RSS wallahs. I am of the belief that no one political persuasion should be allowed to appropriate an entire period of history. History is to be studied and examined critically, and looked at sceptically, which is why one quarter of the book is footnotes of primary and secondary sources.

I don’t think this story of ancient India has been told before in this form—earlier they were pigeonholed in different silos—in one narrative. For example, up to now the Buddhist story was told as part of the Silk Road story so it became a story of China, or the story of Indian numbers was told as part of the story of science. I’m saying that India in this period had an empire of spirit, not of the sword. So, I would like to believe that the effect of Indian thought at this period is like a huge stone thrown in the middle of a still pond and the ripples are running outwards in all directions. That politicians have arguably misused the past for political ends should not stop historians from giving an accurate account and set the record straight.