The Andaman and Nicobar Islands have been a fortress for the Sentinelese and Jarawa tribes for over 60,000 years. Settled in the thick forests of the Sentinel Island, away from the bustling human colony, the Sentinelese are renowned for avoiding any contact with outsiders.

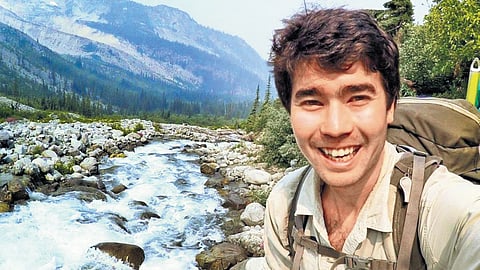

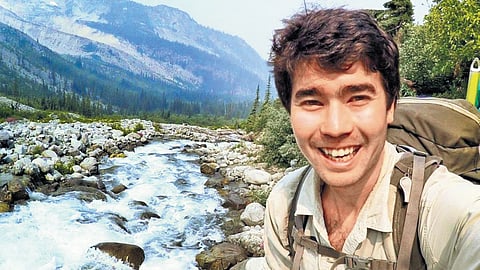

Five years ago, an American evangelical Christian missionary was killed by them after illegally travelling to the North Sentinel Island in an attempt to introduce the tribe to Christianity. Author Sujit Saraf weaves a tale around this 2018 incident and breathes life into the untold stories of the tribe in his new novel, Island (Speaking Tiger).

Nirmal Chandra Mattoo, an acknowledged expert on the tribes of the islands, is Saraf’s protagonist. Mattoo runs a souvenir shop selling fake ‘tribal artifacts’ until an American missionary comes to him seeking his help to visit North Sentinel Island, hoping to bring the Sentinelese to Jesus. Mattoo, who agrees to help, gets embroiled in a bleak turn of events thereafter, setting the tone of the book.

In a chat with TMS, Saraf, who runs Naatak, an Indian theatre company in America, and is the author of The Peacock Throne, which was shortlisted for the Encore Prize in London, talks about Island and how it gives a glimpse into the simple life of the Andamans, the people, its politics while examining the life of those who live on the margins.

Excerpts from the conversation:

How did the Sentinelese spark your interest to write the book?

The 2018 incident was all over the news, especially in the Western media. The absurdity of it – that a missionary would travel all the way to the Andamans to stand and declare in English, to a tribe far older than Christianity, that “Jesus loves you and died for you”, was too delightful to pass up. I could not help imagining the many ways in which this incident might unfold, and the novel was born.

You wrote about the most isolated tribe in the world— what was your research process like?

The English were great chroniclers of the people they ruled. They travelled to far-flung corners of their empire, including the Andamans, and filled great tomes with every little detail about those they found there. These books are now a treasure trove for the writer. Combined with current research by Indian anthropologists, we know a good deal about the Great Andamanese, the Jarawa and the Onge, but not about the Sentinelese. Fortunately, it is believed that the Sentinelese are related – culturally, racially, and linguistically – to these other tribes, so some of this knowledge may be applied to them. I must admit that the Sentinelese will not read this book, so the mistakes in my understanding of them shall remain unknown.

There have been mentions about the current political (the local minister’s speech), religious (Steven’s missionary obsession) situations in the book, is it a commentary on the current socio-political landscape?

Yes. It is difficult to keep a story disconnected from the wider world around it. It so happens that the prime minster flew into Port Blair merely a month after the incident described in the book, to rename a few islands. Ross Island was named after Subhash Chandra Bose, and so on. One set of names – British administrators and naval officers – was replaced by another– Indian historical figures, and neither set has a proper historical connection with these islands. No one bothered to consult, if such consultation is possible, what the people who have lived there for thousands of years call them. It is as if you call my home Name One, and someone shows up to call it Name Two, while I have always called it Name Three but no one asked me. The irony was too rich.

And you cannot talk about the Andamans without noting the government’s push to “develop” it, whatever that means. So, modern politics crept into the novel as a sub-plot.

Who is the protagonist inspired by?

The protagonist is a composite of a few Indian and British anthropologists, English naval officers and administrators.

How long did it take for you to finish the book? Did you have to visit the island often to make the details more authentic?

The novel gestated for five years, but when I write a book, it is quick – the first draft took a week. I did not travel to the Andamans. My family members have gone a few times, and the casual visitor is drawn into the tourist world that has no connection to the tribals. If you go to the Andamans you are presented with its physical wonders and invited to enjoy modern pastimes – snorkelling and diving and sailing. It is not possible to meet the tribals or learn anything about them merely by being in Port Blair or Wandoor. The people of the Andamans have no interest in the tribals. They see them as curiosities or irritants, not as human beings living in their own world.

You are an IITian, how did you make your journey from an engineer to a writer?

I never made the journey. I am still a techie. I have always thought of myself as a writer who does engineering on the side!

Which writers and books have been your inspirations?

The books I admire keep changing as I read more. A novel I read on my flight here - Blue Nights by Joan Didion – affected me deeply, partly because I am partial to stories of deep loss.

What would you like people to take away from Island?

An understanding that there exist many civilisations we do not understand, and that we must practice humility towards the world rather than rampage through it to mould it in our image.