The incident of rape and murder of the daughter of a naval officer in Delhi in 1978 and the death of her brother, who tried to save her, as they were on their way to participate in an All India Radio programme, was national news in the late ’70s and the early ’80s.

This brutality in the heart of the capital was seen as a hit on middle-class India; the Prime Minister had to answer for it in Parliament. The months-long chase of the killers, them being accidentally spotted by two army soldiers from Kerala and Tamil Nadu and their colleagues on the Kalka Mail, and their eventual hanging lend themselves, indeed, to great true-crime writing.

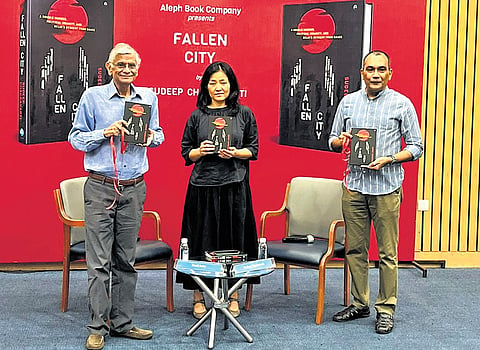

What makes Fallen City (Aleph) by Sudeep Chakravarti a riveting read is the way he has constantly drawn in stories of other instances and types of violence—from the violence of Emergency and the Sikh pogrom after Indira Gandhi’s death, to Kashmiri militant Maqbool Bhat’s hanging and the Paharganj murders of two children in under-construction houses and near a public urinal—and catches Delhi at one of its moments of unravelling. Chakravarti has painted a backdrop of executive high-handedness, administrative slack and civic rot, whose stench is yet to die.

Is the city any different now? For Chakravarti, the capital of India is, as he puts it, a “Love-Hate City”. But for those who treat the city as a pit-stop, or even those who call it home, its charms are many, and sometimes, murderous. Things fall apart, as William Butler Yeats famously suggested, when the centre cannot hold.

Excerpts from a conversation with the author:

Why did you choose the structure you have -- connecting the social and political history of the ’70s and the ’80s to the murder of Geeta and Sanjay Chopra? Why did you feel it important to link it to larger forces at work in Delhi and of India, and why do you think it was important to recall it now?

History never gets old. Political history in a country like ours perhaps even more so. The murders of Geeta and Sanjay have always stayed with me but I did not get an opportunity earlier to write about them, do a generational stock-taking, if you will. As I began to dig deep, the socio-political environment of the 1970s and the 1980s, beginning with the Emergency and ending with the anti-Sikh riots, provided a dark arc of a decade within which the murders were located. It seemed logical to frame the narrative within that arc to provide a full understanding of life and times, a compact history of among the most seismic phases of modernising India. Equally, continuing urban crime, and especially crimes against women, a slack criminal justice system, and chaotic politics show that a mirror from the past can offer reflection and retrospection.

Do you have any personal connection to the story? What were the challenges you faced in writing this book given that the parents refused to be interviewed after almost five decades, given that both Billa and Ranga retracted their confessions? One also gets the sense that you as an author felt that the police investigations were hurried and that the judgment given was one that suited the national mood of closure and wanting death of the two for having killed ‘one of us’?

I do not have a personal connection to the story beyond being of the generation of Geeta and Sanjay, and lived through those times in northern India and Delhi, first as a young adult and then as a young graduate. Those were formative years. They left a great impression that requires dealing with; I chose to do it in a literary manner.

Every book has its particular challenges, and this book, too, had several. I fully expected Geeta and Sanjay’s parents to decline to be interviewed on account of their deep and continuing trauma, and crafted the book by taking that into consideration. Billa and Ranga may have retracted their confessions, but they did legally confess, as repeatedly proven in court. Besides, they never denied the crime, but each continued to blame the killings on the other. I don’t suggest that the police investigation was “hurried”, but that it was clumsy in the beginning. The judicial system acted with the speed they ought to have. Certainly, public outrage had something to do with that speed. And that’s the irony. As we have seen with Nirbhaya and more recently with Tilottama, public outrage is sometimes just the push our interminable judicial system needs.

Since the Geeta and Sanjay Chopra murders, there have been many murders in Delhi, many of them involving young people of the middle class and the upper-middle class, either as victims or perpetrators or both – the Arushi case, Nithari, the Jessica Lall murder, Shivani Bhatnagar, Nirbhaya…. Any thoughts on why a certain kind of violence is endemic to Delhi?

Violent crimes in Delhi, or for that matter in any metropolis, are not just perpetrated against young people or against those from the middle and upper-middle classes; or by them. But these receive maximum traction with the media, and the reading and viewing public. Indeed, in Fallen City I provide glimpses of crimes committed against the poor and destitute that merited barely a mention in the media. It was true then and it remains true now. We seem to be class-conscious about both crime and punishment.

And yet you call Delhi a love-hate city in Fallen City speaking from personal experience. It seems to me quite a cautionary tale – for children, young people, for working women like us who travel home at night after work – never to trust strangers, thumb a lift, depend on police for immediate action.

Our public safety net and criminal justice system aren’t guarantees of a crime-free society. Daily indignities and atrocities committed against children, the young, and women of every age indicate that personal safety is best taken care of by ourselves. It’s also a continuing shame that policing focuses on protecting the powerful rather than the powerless, and civic and social awareness that could actually lessen crimes receive such low priority from governments.

Why did it take so long for you to write a Delhi book? Which are your favourite books set in India’s capital and why? What are you working on next?

Every book has its time and place, and time for gestation and birthing, and an opportunity. I have written several books, and more articles and columns that I can count, but it took this long for me to gather both the mind space and the opportunity to write Fallen City. I hope to write more ‘Delhi’ books; to better understand and even celebrate the place I called home for 25 years.

There are several fine books on, and set in, Delhi. But I particularly recommend two collections of articles and essays by Ronald Vivian Smith, Delhi: Unknown Tales of a City and Lingering Charm of Delhi. They are delightful, insightful and incisive. Smith is a chronicler who needs to be remembered and his work cherished. As for me, I am working on a book of history set in medieval India, a political biography of eastern India, and, far more quietly, a collection of poems.