In the white wooden interiors of Vadehra Gallery, usually the home of India’s modernists, there is, this month, a bit of a disruption. Tractors piled up with well-worn blankets; a bamboo shell of a structure from which a door and a window have been hived out; barricades used to anchor a trailer with a rope so that it does not drift – these are some of the frames hanging solo, or in twos, triptychs or clusters, and entire walls have been given over to them across two floors of the gallery.

Common to all of them is the image of home and the attempt to keep it together from possible collapse—perhaps a metaphor of farmers’ lives buttressed by the temporariness of tarpaulin, thermocol, bamboo, rope, and hope.

One way of looking at it is, you give these structures a push, and they will come down. Another way of looking at it is, they can easily be made to stand again.

Three years after the farmers’ protests—November 2020 to December-2021—stormed the national capital and entered our living rooms, the work of photo-artist Gauri Gill hanging at Vadehra Gallery till March 8, shows the farmers’ ‘homes’ that enabled the farmers' protests.

Gill, whose immersive work in rural communities is done in collaboration with indigenous, marginal and diasporic Indian communities, says she visited the farmers at the Singhu border in 2021 “just to see for myself what was going on” and was filled with awe at “…their spirit, the way those with no power came and sat down on the highways for a full year. If the centre won’t go to the periphery…”, she says trailing off as we meet to discuss her work. For Gill, these homes are “speaking structures and the architecture of resistance…they literally came out of thin air to serve dire necessity”.

Where are the farmers?

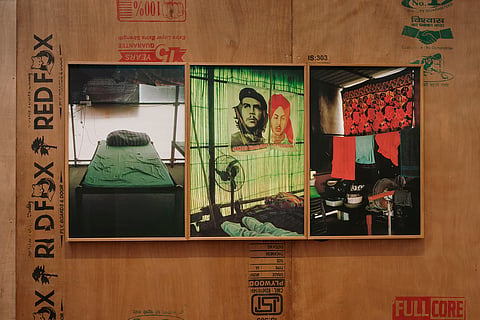

A striking feature of the exhibition is that the photos are mainly faceless except for a pair of feet facing a Che Guevera-Bhagat Singh banner, the back of a farmer lying like a sleeping Buddha, or a circle of slippers outside a curtained door suggesting a gathering for a meeting indoors.

“Absence can be as powerful as presence. I don’t have to have a shot of a protester's face necessarily…. The ingenious structures built by the farmers are their faces too. I was trying to highlight the survival strategies of people in precarity. I am not interested in people drowning.” And that fighting spirit was much in evidence as farmers laid siege to Delhi on the highway in the autumn of 2020.

The event led to new solidarities as farmers from Punjab were also joined by farmers and farmer unions from Haryana and Western UP, among other states, artists and activists. Together they became a community that faced seasonal extremes—searing heat, dengue-fostering rains, a harsh winter and Covid-19—erected ingeniously built homes where there were none, learnt to live besides strangers, made plans, and opened up the possibility of any space, be it a highway, a border, or a back lane, and not just designated protest areas, to be turned into public platforms, and places of resistance.

Gill’s exhibition, ‘The Village on the Highway’, accompanied by additional programming—the performance of Tanashah based on Bhagat Singh’s diaries by Navtej Singh Johar and screenings of talks and films on agrarian crises—serve to remind us that some of the urgent issues faced by the farmers remain, and these houses may come up again; it forces us to encounter them as questions. “The world may go the way of temporary habitations. Gaza through war, the climate crisis migration, decimation of people’s lands…homes sprouting through exigency, sadly may become the norm,” says Gill.

The protest idiom

All over the world, resistance, however, is no longer about overturning the status quo, or taking down of governments, but of negotiating with them. Protests and their manifestations are watched for their form as much as their message and legacy. The art of the Occupy movement—graphic novels, posters, light shows—at times, seems to have laid down more roots than its aims and outcomes. The inflated cube made popular by protesters to throw at cops instead of hard bricks has moved into exhibition spaces as ‘objects of disobedience’.

Protests, in any form, however, are not nothing. In the autumn of 2020, and through all of 2021, Indian farmers, who came with their tractors, trolleys, Banda Bahadur and Bhagat Singh posters, books, cooking utensils, and a popular will to stay put till they were heard, proved that the Indian protester may well be India’s last romantic.

Gauri Gill’s ‘The Village on the Highway’ (2021) is on at Vadehra Gallery, D-40 Defence Colony, Delhi, till March 8