With Partition, a border was cut through schools, and homes in villages and cities of India, unleashing terror and macabre violence that had left millions dead and even more displaced. Decades later, its agonising memories lingers, as its impact silently echoes through generations.

Veteran artist Seema Kholi chronicles a similar tale in her ongoing exhibition ‘Khula Aasman’, for which she draws from family archives and material legacies to reimagine the memory of her ancestral home in Pind Dadan Khan, now in Pakistan. In this work, the artist offers a peek into her deeply personal history, in contrast to her previous work that delved into mythology and philosophy.

“While the work is deeply personal, it resonates with everybody as they are about shared societal or cultural traumas,” she says. “I’m the first generation after Partition. Growing up like many children of that era, my childhood was filled with stories from my parents and relatives about that traumatic period. Yet, it was often the unspoken moments, the heavy silences, that spoke the loudest. These memories, both told and untold, have shaped the foundation of my work.”

Hung on the walls of two venues, the Dara Shikoh Library at Ambedkar University and the Seema Kohli Studio in Okhla, the exhibition showcases a range of mixed-media works that explore the impermanence of all belongings.

New opportunities

Kohli says Partition and the forced migration also led to survival, persistence, and hope. People arrived in new places with little to nothing, yet they managed to adapt and build new lives, she says. “To me, this is a positive narrative. It’s about moving forward, about embracing possibilities in the face of adversity, which is why I chose to call it ‘Khula Aasman’, a celebration of limitless opportunities,” she adds.

An acrylic paint of a hawk flying against the blue sky captures the narrative. Kohli admires its strength and self-sufficiency, visible in the fluid strokes in grey and white and blazing eyes of the predatory bird. “My father often called me Shaheen, comparing me to a hawk.

He would say I would carve my own path, just as the hawk does. But, over time, I realised that more than me, it was my ancestors who truly made their own paths. For me, the hawk serves as a metaphor for that unbending being who creates his/her own space and looks at the world with positivity. It’s a reminder that we all must find our own way,” she adds.

Fragmented memories

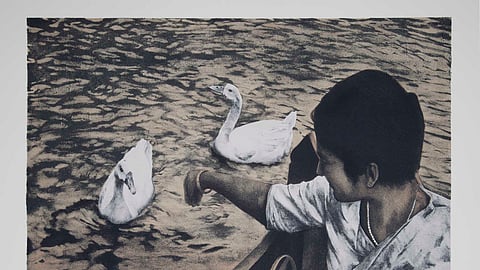

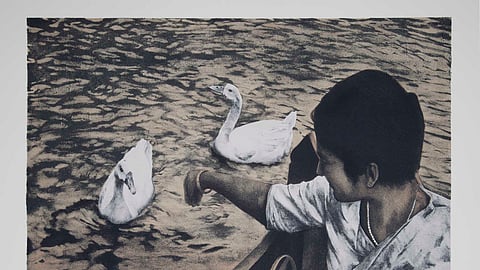

Another work created with silver gelatine print catches the eye. The prints, made from photographs taken in the 1930s with a Fuji camera, have multiple images overlapping one another. Among these images in black and white, one catches the picture of a hand first, spread across an uneven rock. Across it, a shadow of a large building with wide columns stands out. On the left seems to be a yellowed tinted plate with the names of cities etched on it. The images are juxtaposed against lines depicting a heart and buildings as reimagined by Kohli.

“The Fuji camera was a gift to my father by his older brother. The photographs here, along with some images taken by my friend Maria Waseem, who lives in Lahore, travelled all the way to Rawalpindi. She captured our ancestral village, our home, the school my father attended.

I’ve now overlapped these images to create new, contemporary compositions. The older photographs represent the memories of my parents and ancestors, while the new images I’ve crafted by juxtaposing these two images reflect my own imagination,” she says.

These fragmented memories are accompanied by the audio excerpts of her father KD Kohli’s autobiography Mitr Pyare Noo. “The entire show draws from his narratives, his experiences, and the memories of my ancestors. His book also reflects the histories of past 18 generations and the immediate eight generations of my family. This show is based on the book,” she points out.

Bridging gaps

As Kohli weaves a story of time, creating pieces like ‘Gulab Ke Khet’ that have sprawling rose fields of the Choa Saidanshah which were crossed with the help of camels, she also attempts to bridge the geographical gaps in her video installation. In the piece, the doors and windows to her current studio open to familiar alleys as the camera pans across her ancestral house with hanging wooden balconies and arched columns made of lattice.

“What I aimed to do was to create a memory of my ancestors and my own space. I felt these themes have relevance, especially in light of today. The message has to be one of hope and positivity, drawing from the experiences of those who lived through that same period,” she says.