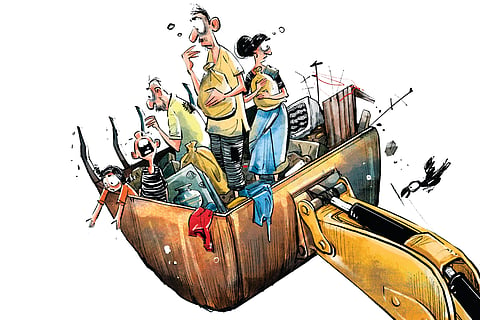

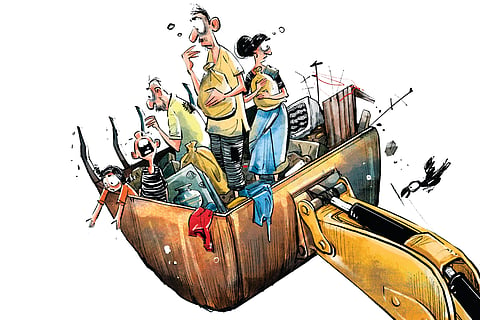

On the morning of June 1, bulldozers rolled into Madrasi Camp in South Delhi’s Jangpura and began tearing through homes that had been painstakingly built over six decades.

Within hours, what had once been a tight-knit, working-class settlement of 370 Tamil-origin families was reduced to mere rubble.

The demolition was carried out by the Public Works Department, under the supervision of the Delhi Police, the Revenue Department, and the Delhi Urban Shelter Improvement Board (DUSIB), following a May 9 order by the Delhi High Court.

The court had deemed the settlement an “unauthorised encroachment” on public land, obstructing drain cleaning efforts near the Barapullah drain. The court directed that rehabilitation be provided as per the Delhi Slum and JJ Rehabilitation and Relocation Policy, 2015. The demolition, the court stated, was essential to prevent potential flooding during the monsoon season.

Yet, a week after the demolition, the reality that emerges is not one of successful relocation or resettlement but one marked by dislocation, distress and disillusionment.

Shattered Dreams

Despite official claims, many former residents remain unhoused and uncertain. Initially, 189 out of the 370 families were found eligible for rehabilitation. A revised list added 26 more, taking the tally to 215 families. “Of the 370 families in Madrasi Camp, 215 were found eligible and duly resettled,” said Urban Development Minister Ashish Sood on June 4.

However, only a fraction of the 189 families deemed eligible for resettlement have moved into government-allotted flats in Narela, approximately 40 kilometres away. Arun Kumar, one of the resettled residents, shared his frustration: “There’s no reliable water supply or power in these flats. Many of us have simply left our belongings there to keep our names intact in the records, but we rent small rooms closer to the city because our livelihoods are here.”

Narela, a distant peripheral locality in North-West Delhi, is poorly connected to the central parts of the city, where many former residents of Madrasi Camp worked as domestic workers, fruit sellers, drivers or waste collectors. The long commute is financially unsustainable for daily wage earners. Anand, whose family was also displaced, has had to temporarily split up. “My children are staying at a friend’s place in East of Kailash. I’m sleeping at the demolition site while I look for a room to rent. It’s very stressful,” he said.

Shiva, who lived in the camp for more than 20 years, still hasn’t left. “I stayed back because I had nowhere else to go. If I leave even this rubble, I will be completely homeless.”

Infra Unfit for Rehabilitation

While DUSIB and the Delhi Development Authority (DDA) had assured the court that basic amenities would be available in the Narela flats by May 20, residents paint a different picture. “There’s no electricity for hours and the water is irregular. There are no grocery shops or clinics nearby and the place feels deserted,” said Arun. Moreover, the new flats do not suit the needs of people accustomed to life in jhuggi clusters.

“Where do I park my fruit cart in a high-rise building?” asked Muthu, who now travels nearly two hours each day from his temporary accommodation back to Jangpura for work. Children’s education has also been disrupted. Several students attended nearby Tamil-medium schools or local government institutions.

“My daughters’ school was within walking distance from the camp. There are no Tamil-medium schools near Narela. I don’t know what we’ll do when school reopens,” said Ganesan, a father of two. Kanan, another resident, pointed out that only a few have been properly resettled.

“The DDA claims that 215 families were shifted, but 26 names on that list haven’t been given allotment letters. We’re on the list, but they say they are still processing papers. Meanwhile, we are homeless. Where do we go now?” he asked.

Legal Roadblocks

The process of accessing possession letters and relocation documents has been opaque and burdensome for many residents. Many are illiterate and struggle to navigate the complex paperwork involved. “There is no one to guide us,” said Janaki, whose family was among those evicted.

Saroj, a 29-year-old woman who moved to the camp 12 years ago, said her family was not even considered for rehabilitation. “They say we haven’t been here long enough. But we’ve made this place our home. Don’t we deserve dignity too?” she asked. The community’s attempts to challenge the demolition order in higher courts have met with resistance. “The High Court allowed the demolition based on photographs of a single clean flat. That was enough for them to assume all was well in Narela,” said Kanan. “Now, the Supreme Court isn’t even hearing us.”

Promises and Betrayal

Ahead of previous elections, several political parties had promised in-situ rehabilitation under the ‘Jahan Jhuggi, Wahan Makan’ scheme.

Residents now say they feel betrayed. “MLA Tarvinder Singh Marwah promised he’d ensure we wouldn’t be moved. Now he is nowhere to be found,” said one resident.

Former Delhi minister Saurabh Bharadwaj of the Aam Aadmi Party, now in Opposition, criticised the BJP-led government for “breaking its promises” and called on Tamil Nadu Chief Minister M.K. Stalin to intervene. The Tamil Nadu government has announced plans to assist those wanting to return to the state and has tasked its Delhi liaison office with coordinating support.

But many families say returning to Tamil Nadu is not an option. “We were born here, raised here. Our lives are here,” said Lakshmi Sunil, 67, who moved to Madrasi Camp as a child. “How can we go back to a village we don’t even remember?”

Economic Collapse

For many, the demolition of Madrasi Camp isn’t just the loss of shelter — it’s the destruction of a way of life. The community, forged over decades by shared language, festivals, food and routines, is now fractured.

“Earlier, we knew everyone. There was a system of support. Someone would babysit your child, another would help with groceries. That is all gone now,” said Rani, a domestic worker. Financially, the move has been catastrophic. “Our earnings were just enough to pay for food and a little rent. Now we have to spend hours commuting or pay higher rent near the city,” said Muthu.

“There are days I don’t earn anything after covering travel costs.” Some, like Anand, now face difficulties in even finding rentals. “Without address proof or documents, landlords don’t want to rent to us. Some are charging advance deposits we can’t afford.”

A Community Left Behind

While the state government insists that the demolition was carried out in accordance with the law, with proper rehabilitation plans in place, those affected tells a different story — one of half-fulfilled promises, fractured support systems and a community cast adrift.

The sight of belongings scattered across open fields in Jangpura, families cooking on makeshift stoves and children sitting on plastic sheets doing homework amidst the rubble is a stark reminder of what forced development can do to the most vulnerable.

“We all have been left here to die,” said Lakshmi, echoing a sentiment shared by many. As the national capital braces for another monsoon season, the Barapullah drain may indeed be clearer, but the human cost of this so-called progress is undeniable. Hundreds of families, whose homes once stood along its banks, now find themselves on the edge of survival — not just fighting for housing, but for their dignity.

Political Blame Game

Chief Minister Rekha Gupta defended the demolition, stating it was carried out strictly in accordance with multiple court orders aimed at preventing flood disasters in the city.

Gupta pointed out that the slum, located along the Barapullah drain, had been marked for removal by the court on four separate occasions to facilitate drain cleaning and prevent flooding similar to what occurred in 2023. “The court has given clear directives and no government or administration can go against them,” Gupta said.

“Machines needed to be deployed to clean the Barapullah drain and the slum’s presence posed a serious obstruction. If these directives were ignored, we would face the same kind of urban flooding that occurred last year.” She asserted that the residents of the camp had been allotted houses and shifted accordingly.

According to Gupta, this was not an isolated case, and similar eviction and rehabilitation actions had been undertaken in other parts of the city, including Railway Colony, where encroachments near railway tracks were cleared by the authorities.

Gupta criticised the AAP for “politicising” what she called a legal process. She questioned, “Who will take responsibility if lives are lost due to floodwaters? Will it be Atishi, Saurabh Bharadwaj or Arvind Kejriwal? The court has done what was required to ensure public safety.”

She also claimed that the BJP-led Delhi government was prioritising infrastructure and welfare, with development projects worth Rs 700 crore underway across the city, something, she said, was never achieved under the AAP or previous Congress administrations. Gupta’s comments came in response to sharp criticism from AAP leader and Delhi Assembly LoP Atishi, who visited the site after the demolition on June 1.

In a social media post, Atishi accused the BJP of betrayal, saying, “BJP had promised ‘jahan jhuggi, wahan makaan’ but demolished the Madrasi camp right after winning the election.” She added that people at the site were devastated.

“Women, elderly and youth alike were weeping. They said voting for BJP was a mistake. If Kejriwal were here, he wouldn’t have allowed this to happen,” Atishi wrote.

Demolition at Bhoomiheen Camp

The demolition of Madrasi Camp is not an isolated incident. Last month, another demolition took place at Bhoomiheen Camp in Govindpuri, sparking legal and political debates. Despite ongoing court proceedings, the DDA proceeded with demolishing hundreds of hutments, affecting several petitioners still in litigation.

Earlier this week, as a vacation bench of Justices Tushar Rao Gedela and Harish Vaidyanathan Shankar was set to hear pleas from residents seeking a stay on the demolition, DDA officials began razing homes. The court refused to intervene, citing compliance with earlier orders from a single-judge bench.

Earlier rulings by Justice Dharmesh Sharma, on May 26 and May 30, dismissed petitions from residents contesting the eviction. Many of the affected individuals, migrant workers from Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and West Bengal, argued that the demolition violated the Delhi Slum & JJ Rehabilitation Policy, alleging that the surveys determining eligibility for resettlement were conducted by an outsourced agency without due process.

However, Justice Sharma upheld the DDA’s actions, stating they had adhered to all procedures and that the petitioners did not have a vested right to rehabilitation.

The court also pointed out that delays due to interim stays had escalated public expenditure, with over Rs 835 crore already spent on in-situ rehabilitation.

In total, 1,618 structures were present at the site, with 935 demolished. The DDA clarified that these belonged to individuals whose petitions had been dismissed by the HC.

According to the Delhi Urban Shelter Improvement Board’s (DUSIB) guidelines, only those with proof of residence prior to January 1, 2015, were eligible for rehabilitation, with 1,862 households allotted EWS flats at Kalkaji Extension. With the next hearing in the matter scheduled for July 7, many displaced residents remain in limbo as debates over policy implementation and legal rights continue.