Beauty, devotion, symbolism: London gets to see over 300 Pichvais in July

Cultural revivalist and founder, atelier Pichvai Tradition & Beyond, Pooja Singhal of Delhi is mounting over 300 artworks at the prestigious Mall Galleries in London known for curating figurative art from July 2-6. She grew up surrounded by textiles, objects, and stories; her mother was an avid collector of traditional Indian art. Her journey as a collector, curator, and aesthetician has been an organic extension of a lifelong relationship with Indian art and craft. A conversation:

What is the theme of the upcoming London exhibition on pichwais? What is its aim as I am sure pichwais are not new in London or for a London audience given that its museums are rich in Asian / Indian art?

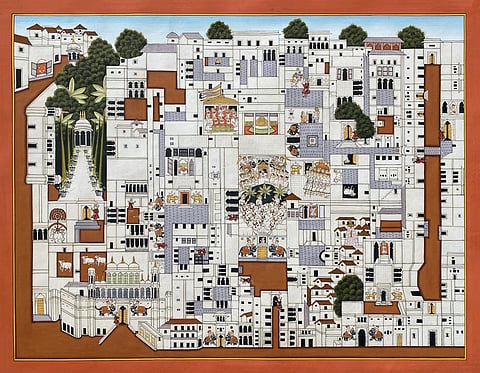

My upcoming exhibition, titled Feast, Melody and Adornment at Mall Galleries in London this July, is a landmark moment for us, celebrating a decade of my atelier Pichvai Tradition & Beyond. It is the first time Pichwai artwork is being presented on this scale to a global audience - we are showing over 350 hand-painted works spanning a hundred years. To present it in the heart of London’s art district is deeply gratifying; London has long appreciated Indian art, but this show invites viewers to experience Pichwai as a living tradition.

The title draws from Raag (melody),, Bhog (feast), and Shringar (adornment, which are central to the Pushtimarg tradition and daily worship of Shrinathji. This triad shapes the structure of the exhibition, which includes both sacred historical works and more contemporary interpretations, including the Greyscale series and others (mentioned above)

What makes this show particularly special is the venue itself. Mall Galleries is known for their curatorial excellence and their commitment to artistic mentorship and socially responsible patronage, both values that align with my own. Just as they support artists through education and exhibition, our atelier in Udaipur nurtures master artists, sustains intergenerational knowledge, and bridges heritage with contemporary relevance.

This shared ethos of accessibility, sustainability, and ethical engagement makes Mall Galleries a fitting space for Pichwai’s international foray. My hope is that this exhibition not only fosters deeper appreciation for the intricacy and devotion of the art form, but also opens up meaningful conversations about how traditional practices can thrive in today’s cultural landscape.

This ethos of accessibility, sustainability, and ethical engagement is at the heart of my practice. My hope is that this exhibition not only fosters deeper appreciation for the intricacy and devotion of the art form, but also opens up meaningful conversations about how traditional practices can thrive in today’s cultural landscape.

How many artists and artwork are being shown and what was the criterion of curation / selection?

Over 350+ works are to be showcased at Feast, Melody & Adornment, that include traditional pieces of art as well as contemporary reimaginations.

Please tell us about your journey as a collector, curator and aesthetician. What was your first collection?

My journey as a collector, curator, and aesthetician has been an organic extension of a lifelong relationship with Indian art and craft. I grew up surrounded by textiles, objects, and stories; my mother was an avid collector of traditional Indian art, and aesthetics were always part of my environment. What began as a personal collection rooted in emotional connection gradually evolved into a more focused vision.

The Pichwai art form particularly captivated me, given its devotional depth, intricacy, and layered symbolism. I realised it hadn’t been given the contemporary attention it deserved, which led to the founding of my atelier, Pichvai Tradition & Beyond a decade ago. Through the atelier, I work closely with artists to preserve and reinterpret the tradition for today’s audience.

Curation, for me, is about storytelling and creating conversations around heritage. Being an aesthetician means nurturing that sensibility through objects, and also through experience, research, and form. At the core, my journey has been about commitment to craft, legacy, and relevance.

My first collection began with a wall of works by Zarina Hashmi, which I encountered at the India Art Fair. I was immediately drawn to them — there was something deeply compelling about the way her pieces communicated both order and emotion. I’ve always had an affinity for ink on paper and sketches, and Zarina’s work, while minimal in form, carries depth and quiet intensity, a combination that resonates with me.

What got you interested in the Pichwais?

My interest in Pichwais began as an emotional response; I was struck by their visual richness, intricacy, and quiet spiritual power. There was something moving in how beauty, devotion, and symbolism came together so seamlessly.

As I delved deeper, I realised how underrepresented the art form was beyond temple spaces and private collections. Despite its historical significance, I felt it hadn’t been given its due credit, and contemporary recognition.

That realisation pushed me to act to preserve Pichwai, and to help the artform to evolve meaningfully. Pichvai Tradition & Beyond was born out of that impulse: to honour tradition while making it resonate with today’s world.

What are the particularities of pichwais made in different cities of Rajasthan?

Pichwais are not traditionally made in other cities of Rajasthan; they originated in Nathdwara, a town near Udaipur, which is where I am from. While Rajasthan is home to several schools of miniature painting, Pichwai began as a more folk-inspired traditional art within the Nathdwara temple community. Over time, particularly following the influence of Mughal aesthetics, the art form absorbed a certain refinement and delicacy associated with miniature painting.

Today, Pichwais are produced in many parts of India, but the original and most revered style remains that of the Nathdwara school, where the tradition first took root.

What are the kind of Pichwais you personally collect?

My personal collection of Pichwais spans a wide timeline, with some pieces dating as far back as the 16th century. It includes a mix of textiles, works on paper, and more recent interpretations by contemporary artists.

Pichwai is an incredibly diverse and layered art form, and my passion lies in collecting across its many styles and periods. My aim has always been to build a collection that, in its breadth, traces the evolution and history of the tradition over the past 300 to 400 years. It’s an ongoing endeavour, but I do feel I’m well on my way.

I believe your endeavour is to modernise pichwais? Please explain with examples in form, colour and content what modernisation would mean in the context of pichwais.

I would not call it modernisation in the conventional sense: I would say it is more about reimagining the Pichwai art form while staying true to its spirit. The intention has never been to dilute the tradition, but to allow it to breathe and evolve.

For instance, in terms of form, we have moved beyond the traditional rectangular canvases to explore miniature as well as larger-scale works, circular canvases, scrolls, and even architectural formats such as jharokhas that respond to contemporary spaces.

We often step away from the dense, saturated palette of traditional Pichwais and use more restrained or tonal schemes, such as indigo, golds, pastel shades and even monochromes, which can bring a quiet power to the work while retaining its devotional depth.

When it comes to content, we try to distill the narrative. Rather than illustrating a full temple scene with all 24 cows, lotuses, and rituals, we might focus on a single motif such as a cow, a tree, or the moon, sometimes with chevron motifs serving as contemporary backgrounds. The essence remains, but the language becomes more minimal, more meditative.

I wear many hats, as a patron, a curator, a gallerist, and atelier lead, often switching roles in a day to ensure each aspect of the initiative is nurtured with care and intention. My aim is not about making pichwai ‘modern’, rather it is about creating space for tradition to engage with a contemporary aesthetic and consciousness.

Curating the London exhibition was a challenging, and at the same time, rewarding experience. London has a large, discerning Indian diaspora, many of whom are familiar with the traditional iconography and devotional context of Pichwai art. At the same time, it was essential to make the exhibition accessible and contextualised to those with no prior knowledge of Lord Krishna, Nathdwara, or the cultural context of Udaipur.

The show is therefore structured in two parts. One half focuses on the revival of traditional Pichwais, art that is rooted in the original aesthetic and spiritual intent of the form. The other half consists of my own reimaginings - works that deconstruct the motifs and visual language of Pichwai, removing religious context altogether. These pieces have been specially commissioned and reinterpreted in softer, more international palettes that include pastel tones, greyscale, and even black and white, moving away from the deep, traditional Indian hues. This section also includes a body of sketches, which form part of the Pichvai Tradition & Beyond collection, offering a fresh, contemporary perspective on this historic art form.

How have you tried to build a community that would patronise pichwai makers?

Building a community around Pichwai has always been central to my vision, since to me preservation without people has no meaning. When I founded Pichvai Tradition & Beyond in 2015, the goal wasn’t just to revive an art form, but to create a sustainable, dignified ecosystem for the artists who keep it alive.

Today, the atelier works with over 40 to 60 artists at any given time, many of them second- or third-generation practitioners from the famous Chitrakaron ki Galli in Nathdwara, the historic neighbourhood known for its painter families. We focus not just on craftsmanship, but also on mentorship, fair wages, and restoring pride in the practice , so younger artists can see a viable and fulfilling future in continuing this tradition. A core part of our process is rooted in the guru-shishya parampara (teacher-student tradition) where senior artists train and guide younger ones, ensuring intergenerational knowledge is passed down with rigour and care.

To cultivate a wider community of patrons, I have curated exhibitions that go beyond the visual, drawing deeply from the devotional and ritualistic context of the art. Some of our most meaningful shows have been built around thematic ideas like Chhapan Bhog, the elaborate 56-dish offering to Shrinathji as part of worship, and Raag, the sonic moods associated with each time of day. These layered curatorial approaches help audiences engage with Pichwai not just as an art form, but as a tradition steeped in feeling, rhythm, and ritual.

Through exhibitions, publications, or immersive experiences, the aim is always to create a deeper connection so that appreciation transforms into sustained patronage, and the art continues to thrive, both within the community that creates it and the one that supports it.