The boat rocked gently as we stepped in — the hand-painted blue has chipped away at places to reveal worn out wood, as the vessel stood tethered at Nigambodh Ghat on the sultry afternoon. The cemented steps lay in ruin — thick moss obscuring its edges and vegetation emerging from its cracks — before disappearing into the murky waters.

The river gurgled beneath — a dark, thick muck of industrial and human discharges, rotting garlands and religious offerings, broken idols and plastic waste, shrouding any semblance of water. It clung to the oar with every heave, black and stinking.

Past the screeching lanes of Kashmere Gate ISBT, where buses honk and snarl, a narrow lane opposite the Marghat Wale Hanuman Baba temple veers off towards the Nigambodh Ghat — an ancient cremation ground at the heart of the Old City. Here, the Yamuna looks forsaken; the river here doesn’t flow, it festers.

We spent over two hours on the boat as it navigated the Yamuna waterways, taking us along the sprawling cremation grounds, stretching from Vasudev Ghat upstream to somewhere beyond the Yamuna rail bridge, where the lines between ‘authorised’ and ‘unauthorised’ become blurry.

A ‘state-of-the-art’ desilting machine stands defiantly near Nigambodh Ghat. All through the day, it removes the sludge collecting along the banks, piling it neatly on concrete corners, only to be washed back into the river when the rain arrive. The machinery apparently cleans only for the files, not the future.

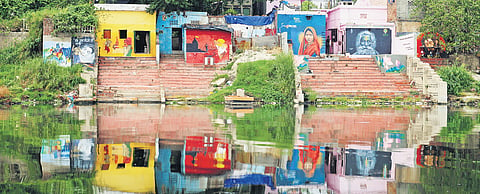

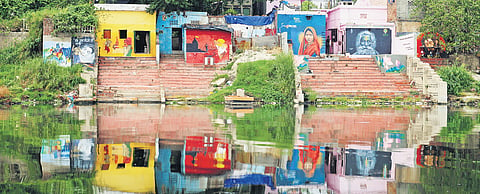

Yet, there are people here. Signs of human life lie strewn around — rickety slums stretch right upto the waterfront where the ghat descends into the murk, decrepit shrines with their fading walls and cracked domes stand stupefied, while woman gingerly negotiates the mud and moss-lined steps as she brings her washings to the river. As the narrow vessel inched along, the walls along the ghats opened up to reveal vibrant murals along the waterway — Gods and man painted in bold strokes and bright colours.

As one edges closer to the banks, however, the stench of sewage pierces the nostril, only to be cut intermittently by the scent of incense from some nameless temple; here, along the cremation ground, this juncture between life and death, faith and filth co-exist.

Stray dogs and stray children rummage through burnt offerings and discarded food packaging along the banks of Yamuna, a jarring sight, in stark opposition of our urban sensiblities.

Near the edge, two boys wade waist-deep in the murk, each holding a magnetic rod tied to a fraying rope. “Is se lohe ki cheezen nikalte hain (This fishes out metallic objects),” one said with a grin, revealing tobacco-stained teeth. Every day, they pull up rusted metal from the river’s underbelly — coins, tools, sometimes even discarded mobile phones —selling them for scrap.

Fourteen-year-old Veeru has made quite a livelihood for himself, fending for coins in the river as he stands under the railway bridge. “I manage to make some Rs 500-600 daily. I eat something out of it, and some I give to my sister.”

His occupation involves six to seven hours of standing, wading and even plunging into the water clearly unfit for human use.

The boys proudly show off their small boats, fashioned out of planks tied together, plastic jugs for floatation, and coloured with some ill-begotten enamel paint.

However, not every child is equipped with magnetic rods. Sahil, an 11-year-old, relies solely on his bare hands and sharp eyes, holding his breath and diving headlong into the black water. He resurfaces with silt covered hands sometimes, clutching torn polythene bags tossed from trains that pass overhead. He shakes them open one by one, searching for coins or some forgotten trinket.

“Sometimes, I even fish out silver jewellery from the river,” he shrugs. Then, looking at his 14-year-old sister Rashmi waiting on the cemented path, Sahil says, “She is scared of water. I bring her here every day thinking she too will take a dip and we’ll find double our bounty from the river but she never agrees.”

At another bend, two men in their 20s stooped near the bank as they sifted through funeral ashes with a plastic sieve. They are winnowing through remains of the dead for traces of gold or metal — tooth caps, or ornaments fragments that survived the pyre. “Kuch kamane ke liye raakh hi channi parti hai (For a livelihood, we must sieve through ash),” he says, expressionless. For some, the Yamuna is not just a lifeline — its the last resort.

Only few steps from the river’s edge, families move in and out of their makeshift habitations. Some are tin shacks. Others are tarpaulin stretched over bamboo sticks. They fill their buckets from tankers, single taps or hand-pumps. “There is water, but it isn’t clean,” a woman says, holding a baby to her hip. “Yamuna humare liye wardhan bhi hai, aur shraap bhi (Yamuna, for us, is both boon, and curse).”

More than 5,000 people live at Nigambodh Ghat. Their lives are tethered to a river no longer clean, no longer holy, yet, theirs. The Yamuna gives them sustenance, and a sense of continuity. It also takes their health, their dignity, and often, their futures.