Just 12 days after its launch, Pratap, an Urdu-language newspaper that had started to protest against British oppression, was censored by the colonial government. Its founder, Mahashay Krishan, was arrested and sent to jail. Although he was released after four months, the ban on the newspaper remained in place for another year.

Launched on April 11, 1919, in Lahore's Gawalmandi area, Pratap eventually outlived the British Raj and survived the upheavals of Partition and displacement that followed. It stood firm during press restrictions at the time of the Emergency of 1975 and also endured the height of Punjab’s militancy in the 1980s.

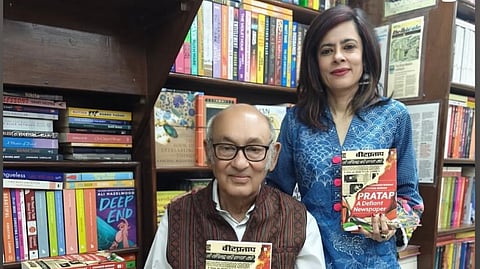

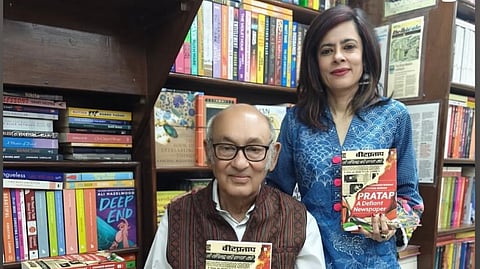

The book Pratap: A Defiant Newspaper (HarperCollins), written by father-daughter duo Chander Mohan and Jyotsna Mohan, tells the compelling story of a newspaper shaped by courage and the people who steered it. Chander, Krishan’s grandson, carried forward Pratap’s legacy after his grandfather and father, Virendra. The book, therefore, is as much a biography of the newspaper as it is of the family.

The spirit of defiance

“There was a story to be told about the newspaper, and also about my father [Virendra], who was a peer of Bhagat Singh. The title [‘Pratap: A Defiant Newspaper’] indicates the spirit of defiance — against the British, against the government, against militants,” says Chander, explaining why the family felt a book was needed.

Jyotsna adds that the newspaper’s wide reach, its “unwavering editorial voice”, and the respect it gained from across households contributed to its legacy. “Pratap was an Urdu newspaper. Urdu was the language of the courts and of the common people, so it had a very wide reach. The newspaper was read not just across undivided Punjab, but far beyond it.” She further notes that the newspaper was fondly remembered by the people — and even today, when one mentions the name, there’s a sense of recognition and respect.

Although much of the newspaper’s archival material was lost in Lahore during Partition, Chander considers himself fortunate that his father had left behind a detailed account of his life. During the Emergency, Virendra decided that he would not write editorials only to have them censored. Instead, he began documenting his own life history.

The authors also spoke to people who had lived through that period and drew on other material preserved at their home.

A newspaper reborn

Born Radhakrishan Vohra, Mahashay Krishan was the only son in a family, “with no tradition of learning or writing”. Radhakrishan later rebelled against Hindu orthodoxy under the influence of the Arya Samaj, adopted a puritanical life, and opposed the caste system.

The book documents how “once India became independent, Krishan turned his pen against the government of the day for what he perceived were shortcomings in their policies.” His son, Virendra followed in his footsteps, equally active and idealistic in outlook.

Chander was just a year old when the Partition forced his family to flee Lahore, leaving behind their home and status. However, after enduring relentless hardship, a sense of normalcy finally returned. Pratap resumed publication — this time from Jalandhar — while the Delhi edition was managed by Virendra’s brother, Narendra. In early 1956, their Hindi daily Vir Pratap was also launched.

A language displaced

After Partition, Punjabi became the dominant language of Punjab in India, and Urdu took a backseat. The authors observe that while the vast majority of Urdu newspapers of British India — 350 out of 450 — stayed in post-Partition India, the language was eventually “marginalized”. “In a polarized, misinformed environment,” the book explains, “it has also been ghettoized by a section that considers the language itself to be anti-national.”

Poet and writer Gulzar, quoted in the book, however, rejects the notion that Urdu is nearing extinction. “Urdu script may not be as prevalent or common today, because professionally it is not required, but the script isn’t the language itself. The language itself is still alive, as it always was. Urdu and Hindi are essentially the same language; it is the script that keeps varying. Urdu was born in India; it is not foreign,” he notes.

The end of an era

The era of Pratap came to an end in 1994 when it shut down operations; by then, corporatisation had begun to take a hold in the industry. Determined not to compromise their principles, the decision was taken to shut down Vir Pratap in 2017 too.

“It was not an easy decision,” Chander writes, “People may say what my grandfather started, I closed down — it was a moral dilemma… in hindsight, it feels like the right decision. Journalism as we knew it is over.”

Speaking on this tough call, he tells TMS, “Pratap was a product of a different era. That era is no longer there. That ideology is not there. That frankness is no longer there.” Rising commercial pressures and the entry of corporate interests, he adds, made it difficult to maintain the newspaper’s historic values. “We thought the paper had a very historic role during its golden period. We could not let it fall into a decline. We didn’t want to make any commercial compromises.”

“Vo afsāna jise anjām tak laanā na ho mumkin, use ik ḳhūb-sūrat mod de kar chhodnā achchhā (It is better to end a story at a beautiful turning point than let it falter),” says Chander quoting the poet Sahir Ludhianvi.

Having worked in television news, Jyotsna is critical of the medium’s decline. “Television news has compromised what journalism was. There’s no accountability, and much of the information is unverified.” While she notes that print media still offers a glimmer of hope, she acknowledges that the industry remains under immense pressure. Ultimately, both authors emphasise that the responsibility for holding institutions to account lies with civil society.

Toward the close of the conversation, Chander points out that the book highlights a lost idealism in public life: “When I look back at the time of the freedom struggle and compare it with today, I feel the level of politics — and of politicians — has fallen sharply. Leaders then were idealists; they had clear aims… Today, there is a total decline in the stature of those who lead us, and that decline is reflected on the streets of India as well.” According to him, Pratap is a timely reminder of what journalism once stood for — a vocation of true courage.