ainters Raja Ravi Varma, Jamini Roy, S. H. Raza — there are many giants among India’s modernists, but F. N. Souza stands alone — defiant and impossible to ignore. Avinash Chandra, by contrast, has remained a quieter presence, admired by those who know but rarely placed at the centre of popular narratives. At ‘Contours of Identity’, curated by senior vice president of DAG, Giles Tillotson, currently on view at DAG, Delhi, Souza and Chandra have been paired. Though separated by a few years in age, both artists left India in the mid-20th century and made London their home during the 1950s and 60s — a period Tillotson describes as radically different from today’s globalised art world. Britain at the time was far less visibly multicultural, and for Indian artists arriving with ambitions shaped by modernism, the encounter was both liberating and constraining.

The exhibition raises the question of what happens when Indian modernism is viewed through the lens of migration, expectation, and self-fashioning.

“Souza and Chandra thought of London as a kind of mecca of modernism,” Tillotson explains. “An escape from India, from provincialism, from restriction.” Yet on arrival, both artists found themselves boxed into a narrative of identity they had not entirely chosen. They were seen — and promoted — as Indian artists first, modernists second. This tension between freedom and categorisation becomes the focus of ‘Contours of Identity’.

Two trajectories, one dilemma

On view at the show are various works by Chandra and Souza juxtaposed against one another reflecting themes of landscape, humanity, sexuality, and memories. Moving from India to London, both artists were championed by influential British critics such as W. G. Archer and George Butcher and they achieved considerable success in the UK.

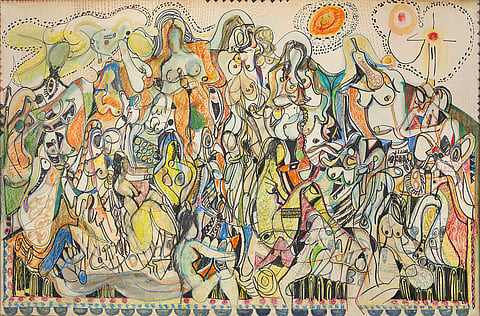

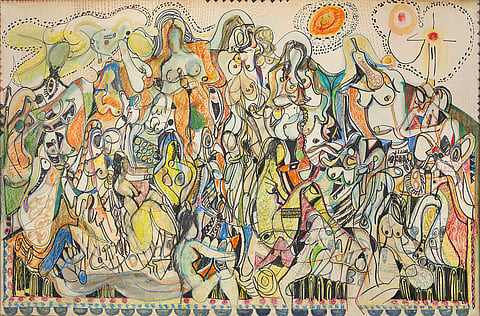

Souza, a founding member of the Progressive Artists’ Group, cultivated a persona as much as a practice. Aggressive, abrasive, and deliberately provocative, he was the “angry young man” of modern Indian art. His paintings — particularly his nudes — are confrontational, distorted, and unapologetically sexual. Some of the etchings now on view, for British audiences of the time, were often read through an Orientalist lens: the rawness of his work explained away as something essentially Indian.

Chandra, on the other hand, internalised these tensions. His work moves away from figuration into abstraction, rhythm, and symbolic form. Sexuality is present, but it is folded into a larger visual language — what Tillotson describes as “bound up with lots of other things”. Bodies dissolve into landscapes, forms merge and repeat, and desire becomes metaphor rather than spectacle. Tillotson notes that both artists used sexuality as a route into inner consciousness. For observers, this was often racialised; for the artists themselves, it was simply a way of being.

A recurring idea in the show is the “negotiation of identity”, which Tillotson explains occurred not on canvas, but in reception. Critics, collectors, and institutions projected meanings onto the work that shaped how the artists were seen — and how they saw themselves.

He recalls an anecdote about Chandra’s early years in London: “He was trying to find a gallery that would take and show his work. One gallery said, ‘look, can’t you paint Indian themes? What’s interesting about you is that you’re from India. Why are there no tigers in your paintings’. You can imagine how exasperated Chandra would be: “I came away from India precisely to explore other things, and you’re putting me back in a box,” he said, adding that the moment is a lingering reminder of how identity could function as both opportunity and constraint.

One can say that their distance from India allowed both artists to engage with their Indianness more honestly. “It gave them the freedom and the ability to become what they wanted to become,” notes the curator. But this did not mean nostalgia. Both Souza and Chandra returned frequently to India and continued to exhibit there, but their artistic identities were increasingly formed within a British context. Over time, they became part of a British story of modern art, even as India continued to claim them as its own.

Looking again

Seen together, Souza and Chandra recalibrate each other. As Tillotson puts it, the experience is like sampling perfumes — one scent altering the perception of the next. Their juxtaposition reveals unexpected points of connection alongside sharp contrasts, complicating the myth of the solitary modern genius.

If Souza has long been canonised, Chandra remains less widely known, despite achievements that include being the first Indian artist at Documenta — a contemporary art exhibition which takes place every five years in Kassel, Germany. Tillotson attributes this partly to Souza’s flair for self-publicity and his longer career. Exhibitions like ‘Contours of Identity’ suggest a slow rebalancing — one that expands Indian modernism beyond a handful of known names.