Ink trails, heritage tracks

HYDERABAD: CE introduces Ramesh Karthik Nayak, a fresh literary voice expressing the beliefs of the Banjara community. He was recently invited to Bengaluru Poetry Festival, where he released his debut poetry collection in English called Chakmak

“All of a sudden the tanda filled with howling voices of folk, my mother started howling with them

ahvu...hei...chu...thu...didn’t know why they were howling but I even gave my voice.”

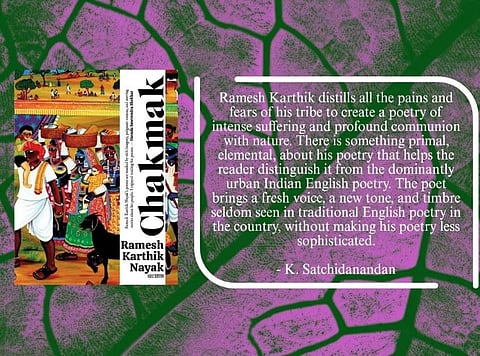

Giving a voice to the experiences, culture and traditions of the Banjara community, 25-year-old Ramesh Karthik Nayak is a refreshing expression in the world of literature. His debut collection of poetry in English, Chakmak (Flintstone) was released recently at Bengaluru Poetry Festival. The above is an excerpt from the poem A Day in the Rainy Season which is a part of the collection.

He has published three books in Telugu — Balder Bandi (Ox Cart, 2018) which is a poetry collection; Dhaavlo (Song of Lament, 2021), a short story collection, and Kesula (Modugu Flower, 2022), a compilation of Banjara stories which he has edited along with Professor Surya Dhananjay.

“The languages I write in, i.e. Telugu and English, are not mine. However, I have insisted on having literature about my community. It is important to speak out, or else with time, people would conclude that our language and culture have vanished,” said Ramesh Karthik. “I dream of bringing Sahitya Gouravam (literary glory and pride) to my indigenous culture,” he added.

Originally named Nunnavath Karthik, he is a member of an ethnic nomadic tribe known by different names such as Lambada in Telangana and Banjara across India. Ramesh hails from Jakranpally Tanda, settled in the Nizamabad district of the state. He began writing in 2014, but a collection of 100 poems he wrote was lost even before he could publish.

However, through his writings on social media and support from friends and teachers, he was able to publish his first poetry collection in Telugu, Balder Bandi in 2018, which now has been included in the postgraduate syllabus of Andhra University. One of his poems Jarer Bati (Jowar Roti), from the newly released Chakmak, has been made part of the undergraduate syllabus of SR & BGNR Government Degree College, Khammam.

Ramesh’s writings have appeared in Exchanges: Journal of Literary Translation, University of IOWA; Poetry at Sangam; Indian Periodical; Live Wire and Outlook India. He was shortlisted for the Sahitya Akademi Yuva Puraskar in Telugu for 2021, 2022, and 2023. He is currently co-editing Phunda, an anthology of Banjara short stories written in Telugu from the Telangana region.

Due to continued nomadic existence, the community has been marginalised in social, economic and political terms. First termed as a ‘Denotified Tribe’ in 1952 and then later added to the ‘Scheduled Tribes’ list, the Banjara community has found traces in Rajasthan and Afghanistan, while being constant migrants and wanderers.

Ramesh’s family came to be settled in a remote village of VV Nagar in Nizamabad, when his grandmothers sold their jewellery and ornaments to buy a small, damp, piece of land near a pond. His parents forced him to get a D.Ed diploma, a course which he failed 18 times. “I was simply not interested in it. I had an interest in literature and wanted to have a proper education. I had to finance my own education and for that, I had to work at a Xerox shop, in book shops, work as an AC mechanic helper and a caterer.

I have even pasted leaflets at a bus stop and sold books at literary events,” he said.

In spite of difficulties, Ramesh finished his Master’s in English last year and is not teaching intermediate school students. When asked how he was able to incorporate the Banjara experiences in his writings, he said, “Only at 12 years of age did I come to know that I belong to this community. I began to notice our dresses, our language, the goddess we worship and our intimate bond with nature and the universe. I became aware of my gypsy identity. However, I am as much a city boy as any other person and what I know about the tanda is through the people who have been deeply connected with it, for example, my grandparents. I would see my grandmother making a jarer baati and I would sing with them during the rains. My heart is connected to the tanda.”

“I began writing on Facebook and as people read my poems, they began to call me ‘Nayak’ which is a name associated with my tribe. One day when the writer Mahasweta Devi passed away, a friend said to me, ‘Why don’t you become a Mahasweta Devi for your people?’ That is when I got the idea to exclusively write about my community. Since then, I have only been concentrating on the plight and pain of the Banjara people; their traditions and beliefs. It has made me stand out in the Telugu community, as someone who has a special voice and a voice that hadn’t been heard yet,” he added.

The community may be known by several names such as Gor, Goriya, Lambana, Tanda, but the members, through their lack of permanent existence, do not have fixed names. “My paternal grandmother calls me Lakya, which is my grandfather’s name. My maternal grandmother calls me Maru’s son,” he said. Hence, having a distinct identity and writing about them has helped him put the local history and lifestyle of his tribe on a global map.

Taking inspiration from Gabriel Garcia Marquez and Toni Morrison, Ramesh says he will continue to write about the clothes, ornaments, jewellery, traditions and beliefs of his community. He is also interested in researching the Roma gypsies, a nomadic tribe in Europe and finding if there is any connection to his own tribe.

Describing his experience of being at the Bengaluru Poetry Festival, he said it was a surreal experience, like a beautiful painting he could never have imagined. “I made my community visit Bangalore with my literature,” he said, concluding with a piece from one of his poems:

“The world is trying to heap the chakmak together,ransack our tribe for stonesand change the Tanda into a haat of banjara tribes The chakmak in the fair were ready to burst with chronicles untold.

You gather the people, the flute disappears, I try fabricating the remaining tale.”